Battle of Waterloo: The Capture of Paris

The Battle of Waterloo, decisive though it was, did not bring the campaign against Napoleon to a conclusion. The allies now had to complete their victory by taking control of France from him and his adherents, and handing it over to the legitimate French authorities. In this step we consider the course of the military campaign and you can read below the text of the military convention which brought hostilities to a close. Wellington’s account of one of his meetings with the French commissioners sent to treat for peace is given as an optional document.

These tasks were not straightforward. First of all, there was a military campaign to complete: Napoleon may have withdrawn into France with his forces in disorder, but invasion would bring with it a great many risks and sensitivities — this was, after all, the country of an ally, the King of France. Secondly, there was the question of establishing a legitimate authority to take control of the country — a point to which we shall return to later.

The allies had been preparing for an invasion of France — this was their strategy for deposing Napoleon — but Wellington and Blücher had not expected to enter French territory until the start of July. Napoleon’s invasion of the Low Countries and his defeat at Waterloo advanced their timetable. Wellington now expected to cross the frontier on 21 June, and he wrote to the Duc de Feltre to have the King of France, Louis XVIII, ready to move and about the arrangements for his lodging and court as he did so. He issued a General Order on 20 June to remind the troops of the character of their movement into France:

As the army is about to enter the French territory, the troops of the nations which are at present under the command of Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington are desired to recollect that their respective sovereigns are the allies of His Majesty the King of France, and that France ought, therefore, to be treated as a friendly country. It is therefore required that nothing should be taken either by officers or soldiers, for which payment be not made. The commissaries of the army [Treasury officials responsible for obtaining provisions] will provide for the wants of the troops in the usual manner, and it is not permitted either to soldiers or officers to extort contributions.

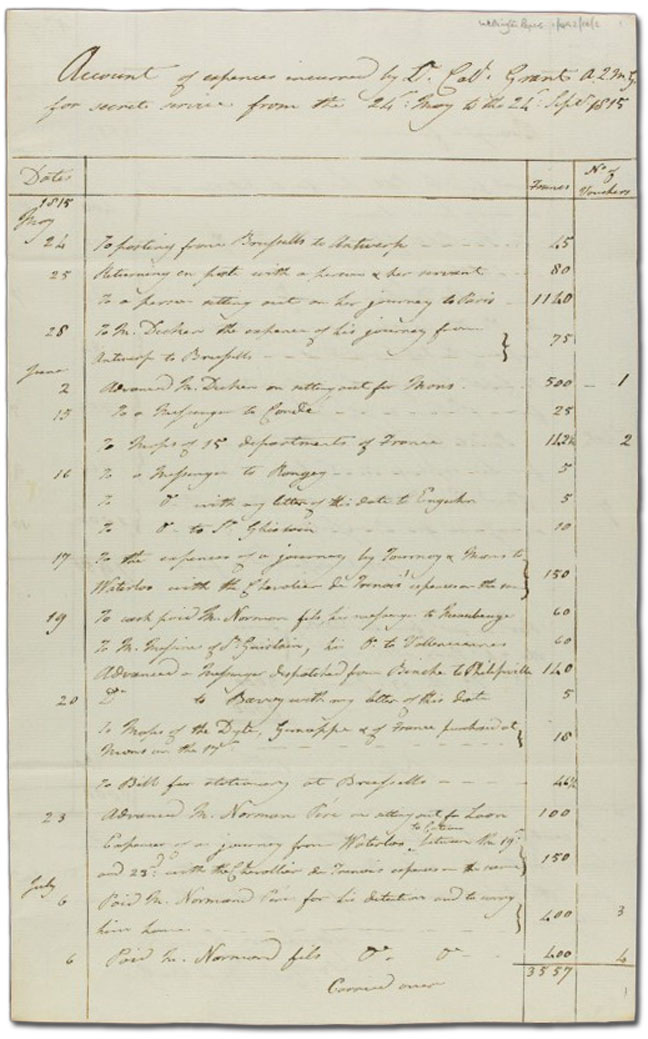

Napoleon expected to continue fighting: in the first instance he asked his forces, along with the gendarmerie and national guard, to assemble on Laon and Rheims — but they were in a very poor state. One part of the army, the 3rd Corps, which had been sent to observe the Prussian army, was thought to have survived intact, and had retreated into France by way of Namur and Dinant. A more immediate impediment, for an allied army about to cross the frontier, were the fortresses of the towns along the border — straightaway Maubeuge and Landrecy were blockaded by the Prussians, and Wellington moved on Valenciennes and Quesnoi. Avesnes surrendered to the Prussians. The Duke of Wellington advised the French king to base himself at Cambrai — which was summoned to surrender on 23 June and taken by force the same day — until the end of military operations: support for Louis XVIII might also mean that some of the fortresses would surrender to him. Even during the period of the Battle of Waterloo, the allies had been gathering intelligence to support their move into France: on 15 June, Colonel Colquhoun Grant had used secret service funds to buy maps of 15 départements of France, with a further purchase on 17 June of 10 more maps — one of Genappe — and of parts of France [Document 1]. His was one of the brigades of cavalry sent against Cambrai on 23 June.

Document 1: Colquhoun Grant’s secret service accounts to September 1815.

Document 1: Colquhoun Grant’s secret service accounts to September 1815.University of Southampton Library, MS 61, Wellington Papers 1/492/16/2. Crown copyright: reproduced by courtesy of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

In the meantime the allied advance on Paris continued — and Wellington was again approached for an armistice. On 2 July, Wellington was at Gonesse, a little to the north-east of Paris, writing to Blücher:

It appears to me that, with the force which you and I have under our command at present, the attack of Paris is a matter of great risk. I am convinced it cannot be made on this side with any hope of success … We must incur a severe loss, if it is necessary, in any case. But in this case it is not necessary. By the delay of a few days we shall have here the army under Marshal Prince Wrede, and the allied sovereigns with it, who will decide upon the measures to be adopted, and success will then be certain with a comparatively trifling loss; or, if we choose it, we can settle all our matters now by agreeing to the proposed armistice.

The terms he considered were that his forces and those of Blücher should remain in their positions; that the French army should withdraw from Paris across the Loire; that Paris should be placed in the hands of the national guard until the French king order otherwise; and fourthly, that a period of notice should be established for withdrawing from the armistice. Wellington believed this would allow the return of the French king to be a peaceful one. ‘It is true we shall not have the vain triumph of entering Paris at the head of our victorious troops’. Blücher was not convinced, on the grounds of what could be seen of the level of resistance in Paris.

Ending hostilities

The question facing Wellington was how to stop the conflict in a way that allowed the French king to have sufficient authority to govern France; the allies were also reluctant to attack Paris and to destroy the capital of Louis XVIII, whom it seemed probable they would restore to the French throne. But Wellington was quite clear that the French army could not be allowed to remain in Paris, nor that the king recover his throne in a way that left him in the hands of the Assemblies, which were seen as Napoleon’s creation and instrument. Fighting continued around Paris on 2 and 3 July, at Meudon and Issy, to the south-west of the capital, in which the French suffered heavy losses. The Prussians were now able to move along the left bank of the Seine, in communication with Wellington’s army by way of the bridge at Argenteuil; and the British army was able to move in force along the left bank of the Seine as well, towards the Pont de Neuilly. At this point, the French asked for a ceasefire on both sides of the Seine and to negotiate a military convention. Agreed at St Cloud on the night of 3 July and ratified the following day, the convention set out the terms on which the French army should evacuate Paris. The terms of this agreement were purely military and did not settle any political question. [Document 3]

Document 3: Translation of part of the Convention of Paris, the military convention for the surrender of Paris, 3 July 1815

Article 1

There will be a suspension of hostilities between the allied armies commanded by His Highness Prince Blücher, His Excellency the Duke of Wellington and the French army under the walls of Paris.

Article 2

Tomorrow the French army will march to a position behind the Loire. The evacuation of Paris will be completed in three days and the movement to take the army behind the Loire will be finished in eight days.

Article 3

The French army will take with it all its matériel [military equipment and munitions], field artillery, military chest [the financial department], horses and the property of the regiments, without any exception. The same will happen with the personnel of the depots and with the personnel of the various branches of the army administration.

Article 4

The sick and the wounded, as well as medical officers which it is necessary to leave with them, will be placed under the special protection of the commanders in chief of the British and Prussian armies.

Article 5

The military and other personnel referred to in Article 4 can, as soon as they are well, rejoin the corps to which they belong.

Article 6

The women and children of all those who belong to the French army will be free to remain in Paris; the women will be able without difficulty to leave Paris to rejoin the army and to carry with them their property and that of their husbands.

Article 7

The officers of the line employed with the fédérés or with the tirailleurs of the national guard, will be able either to rejoin the army, or to return to their homes, or to their place of birth.

Article 8

Tomorrow, 4 July, at midday, Saint Denis, Saint Ouen, Clichy and Neuilly will be handed over. The day after, 5 July, at the same hour, Montmartre will be handed over; the third day, 6 July, all barricades and obstructions will be dismantled.

Article 9

The national guard and the gendarmerie municipale will continue to keep the peace in the city of Paris.

Article 10

The commanders of the British and Prussian armies undertake to respect and to make their subordinates respect the present authorities such as they exist.

Article 11

Public property, with the exception of those linked to war, whether they may belong to the government or to the municipality, will be respected and the allied powers will not intervene in any way in their administration and management.

Article 12

In the same way individuals and private property will be respected: the inhabitants and, in general, all who find themselves in the capital will continue to enjoy their rights and liberties, without being troubled or questioned about anything relating to their business, present or past, their conduct and their political opinions.

Article 13

The foreign troops will not obstruct the provisioning of the capital and will, to the contrary, protect the arrival and free circulation of goods that are sent there.

[WD, xii, pp. 542–4.]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free