The role of transport in economic development

One of the key measures of macroeconomics is economic growth, and logistics and transport play a key part in this.

To encourage economic growth, governments need to invest in logistics infrastructure such as roads, railways, airports and ports. Additionally, governments need state investment to be considerate of the environment and protect citizens’ rights for clean air, decent places to live and work, as well as fundamental human rights and equalities. Businesses are not interested in these issues because there is no profit incentive. Governments in different nations have different attitudes and priorities regarding how much attention they pay to these issues.

In a mixed economy, one of the ways of measuring the success of government’s influence on the economy is by comparing how it has affected logistics and transport growth.

Remember, a government wants an efficient transport system because it allows easier movement of labour from households to firms, goods and services between firms, and from firms to households. Additionally, it allows labour to easily move between firms, and products and services from firms to households. A low unemployment rate demonstrates this is happening.

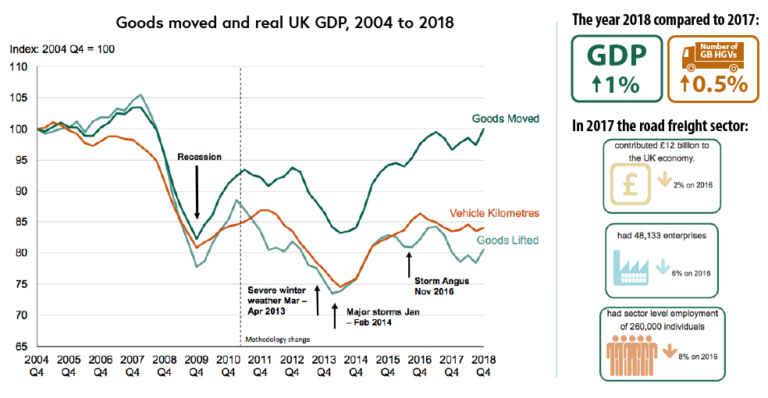

There’s an argument that a direct correlation exists between transport and economic wealth. If we look at the graph of UK GDP growth compared with the number of goods vehicles registered for commercial usage through the operator licensing system, there is a clear correlation (Department for Transport 2019).

Adapted from Department for Transport (2019). Click to expand.

Adapted from Department for Transport (2019). Click to expand.

If we think through the logic of this argument, then the higher the level of economic activity, the greater the need is for efficient transport to ensure goods are in the right place. This creates a demand for improved logistics and transport infrastructure. This leads to demand growing and the multiplier effect kicks in, followed by GDP growth. If greater demand means a country has exceeded their available factors of production, they start to trade with other countries to obtain the scarce resources they need.

Transport and competition

Transport services and the associated infrastructure can also give a state a comparative advantage over other nations’ economies. An example of a comparative advantage in transport can be found in the US rail freight industry. In the UK, we have low bridges and cannot stack containers at all on a train. American trains can be stacked two containers high because they have no height restrictions or low bridges. Therefore, they have a comparative advantage over other countries who have low bridges. The US has an absolute advantage over countries that have no railways, such as most of Africa and South America.

Decoupling transport from GDP

Expecting both GDP and transport activity to keep increasing forever is unrealistic. There has to be a point of marginal utility, where an additional unit of growth has no effect on GDP.

There are also many non-economic factors, such as pollution and traffic jams, which will decouple transport activity from growth of GDP. The use of land can have negative effects on the environment, and no one expects all land to be used for roads and other logistics infrastructure.

Finally, more efficient transport costs less, so GDP should rise faster than transport because of rising productivity and economies of scale, thus demonstrating that decoupling of transport from GDP has occurred.

Supply- or demand-led?

Finally, we need to consider whether transport and logistics service expansion is supply- or demand-led. Why is this important? Because we are interested in causation: we need to know whether logistics is responding to growth that is instigated by our actions and which is creating transport capacity, or whether it is reacting to growth that we have not influenced.

Supply-led is when growth is instigated by your actions. More transport and logistics assets and infrastructure investment by both government and firms will create more capacity to generate products or services, which will create more demand. Investing in infrastructure is a classic move by governments to improve the level of economic growth. More transport, logistics and the related infrastructure leads to economic development. Increasing quality transport facilities leads to access to more markets, and efficient transport is cheaper so more transport is used. Large-scale transport infrastructure projects will indirectly affect the local economy; the multiplier effect kicks in and encourages logistics businesses to grow.

Demand-led growth is not so controllable. Investment in overall economic development leads to demand for transport, so the demand is from consumers. Demand must initially exist to make it worthwhile to provide transport services, whereas supply-led growth is about expanding transport and logistics capacity. Demand can arise from two sources: revealed and latent demand. Revealed demand is based on actual movements of goods, ie people wanting to move more things. Latent demand is the potential demand that can’t be satisfied due to inadequate transport infrastructure. An example of latent demand is if a retail park is built outside of a town; the demand is not there until the project is built.

Your task

Investigate and compare recent GDP statistics with freight or transport movements to prove a link between GDP and logistics. You might like to start by using the data in the downloadable PDF at the bottom of the page. You can explore your own country’s GDP, which is often easily available, but finding transport activity data might be difficult.If the GDP was showing a declining economy, how will this affect investment and growth decisions being made in our scenario at CV1Logistics? Summarise the evidence you’ve used to justify your conclusions.

References

Department for Transport (2019, July 19). Domestic activity of GB-registered HGVs 2018. Office for National Statistics. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/815839/domestic-road-freight-statistics-2018.pdf

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free