Child Survival Rate Advancements in Tanzania

Share this step

Tanzania has achieved its target for the Millennium Development Goal 4 for child survival, yet seen slower progress in reducing newborn and maternal deaths. This case study, summarised by Corinne Armstrong and Dr Neha S. Singh, seeks to understand the country’s mixed progress by looking at the changes in maternal, newborn and child mortality in Tanzania since 1990, and outlining who was being left behind. This article is adapted from Afnan-Holmes, et al. (2015). Tanzania’s Countdown to 2015: an analysis of two decades of progress and gaps for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health, to inform priorities for post-2015. The Lancet Global Health. Vol.3, No.7, e396-e409.

How has Tanzania performed?

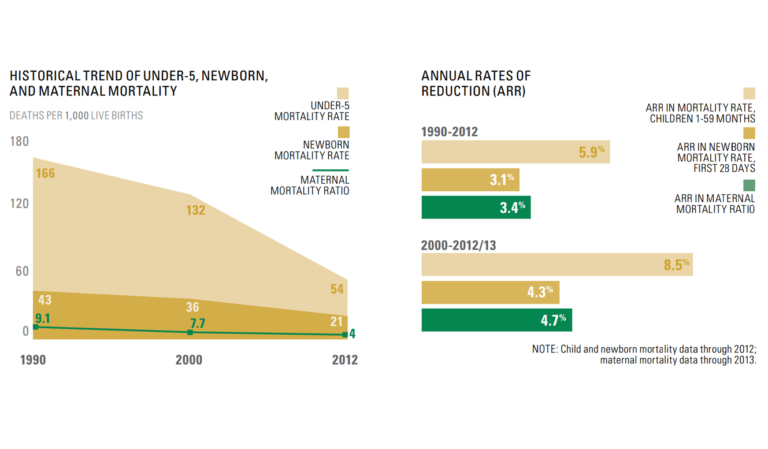

Tanzania has halved the number of deaths to children under five years old per 1000 live births from 166 in 1990, to 54 in 2012. Yet progress is about 50% slower for newborn and maternal deaths.

Tanzania has made remarkable progress for reducing child deaths after the first month of life. Newborn deaths now account for 40% of child deaths nationally, and the rate of progress since 1990 has been half that for children after the first month of life.

Figure 1 (left). Historical trend of under-5, newborn and maternal mortality

Figure 1 (left). Historical trend of under-5, newborn and maternal mortality

Figure 2 (right). Annual rates of reduction (ARR). (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1,2

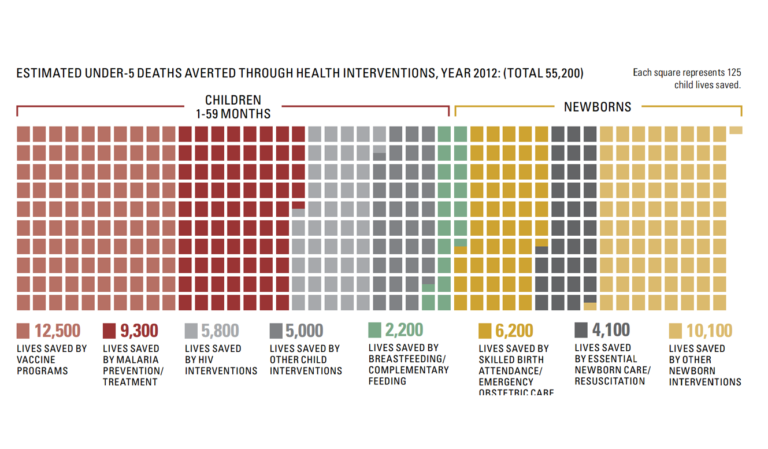

The study highlighted throughout this article used the Lives Saved Tool (LiST) to estimate how many lives have been saved during this period and which interventions may have contributed the most. The most lives saved were estimated to be from vaccine (12,500), malaria (9300) and HIV/AIDS (5800) programmes. An assessment of the health system financing found that these programmes received significantly more donor funding than others.

About 3300 maternal deaths are estimated to have been prevented each year, with the majority (70%) associated with skilled care at birth.

Figure 3. How Tanzania prevented thousands of deaths. (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1,2

Figure 3. How Tanzania prevented thousands of deaths. (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1,2

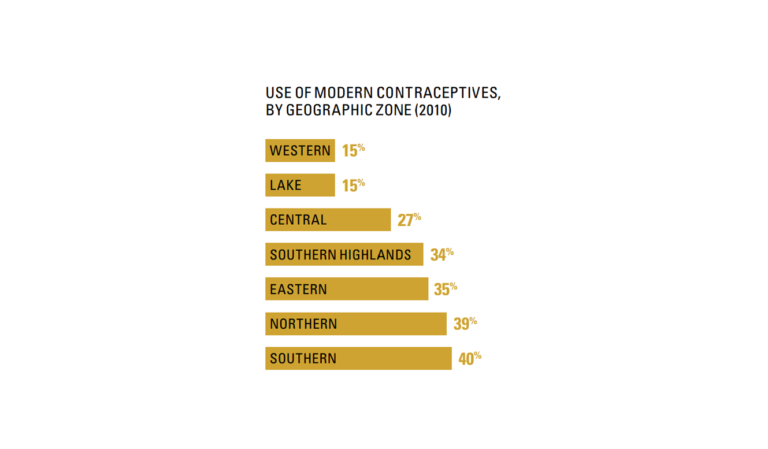

Any assessment of progress in Tanzania needs to take account of its population, which has doubled in size during the past two decades. This has put huge pressure on the healthcare system, in addition other social services such as education, which in turn would also need to have doubled in size just to reach the same proportion. However, the gap for addressing family planning needs has remained the same for 20 years. While modern contraceptive use has increased even in rural areas, there are two geographical regions (Western and Lake zones) where modern contraceptive use remains extremely low.

Figure 4. Use of modern contraceptives, by geographic zone (2010). (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1;2

Figure 4. Use of modern contraceptives, by geographic zone (2010). (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1;2

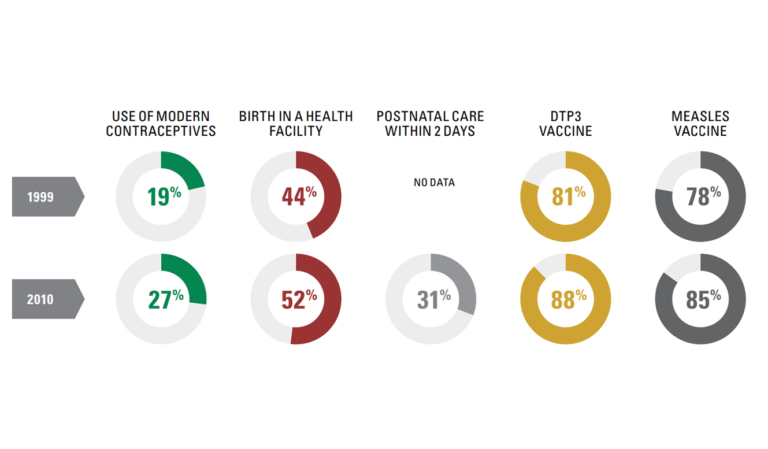

Improving health services around the time of birth are a key missed opportunity. The study reveals that the rural poor are being left behind, with rural women twice as likely to deliver outside a health facility and three times less likely to have a caesarean, in part related to gaps in access, especially to human resources, notably midwives, and to the poor quality of care at birth, including labour and delivery, immediate care after birth and during the postnatal period.

Figure 5. Coverage for family planning and care at birth has lagged. (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1,2

Figure 5. Coverage for family planning and care at birth has lagged. (Afnan-Holmes et al., 2015; Countdown to 2015, 2015).1,2

Why has child survival seen substantial improvements in Tanzania?

Global health agendas have had a clear influence on Tanzania’s policies. Child survival, a priority since the early 1980s, has consistently focused on the primary care level, such as immunisation and integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI). Programmes implemented consistently since the 1990s now have high national coverage, low urban–rural inequity, and more data are available to drive quality improvement. Tanzania was one of the first countries to start implementing IMCI. The cost savings and a 13% reduction in child mortality between 1999 and 2002 prompted national scale-up and district budget funding. Between 2003 and 2010, external financing for child health increased more than three-fold.

Why has Tanzania not shown substantial change in maternal survival despite continued high-level attention to this issue?

In 1987, Tanzania was one of the first sub-Saharan African countries to adopt the Safe Motherhood Initiative, which led to two decades of high-level attention. However, implementation has been patchy, especially at a large scale. From the outset, the global policy community was divided over maternal health strategies that have changed several times in the past few decades, from traditional birth attendants to skilled attendance at birth versus emergency obstetric care. In Tanzania, low quality of care, especially obstetric care, and disrespectful care might discourage attendance or cause women to bypass facilities that are closer to their homes. The health facility births strategy relies on a functioning healthcare system with good referral, yet consensus is absent on how to achieve this in weaker health systems. Donor funding has been lower for maternal health than for child health, and much lower than that for HIV. Sustained funding is essential to close gaps in midwifery and human resources, and to strengthen the wider health system.

Why has newborn survival seen little progress and only recently received attention in Tanzania?

Newborn survival was a latecomer on the global health agenda, appearing almost 20 years after maternal survival. The 2005 Lancet Neonatal Survival Series catalysed the Tanzanian Newborn Situation Analysis, providing subnational data and focusing on action and implementation, including district-level rollout of IMCI adapted to include ill newborns, kangaroo mother care, and neonatal resuscitation. Tanzania was one of three countries to undertake a national scale-up of neonatal resuscitation in the ‘Helping Babies Breathe’ initiative, with strong national leadership and an evaluation showing significant reduction in neonatal mortality. Tanzania could make rapid progress if high-impact interventions for newborns are now scaled up. However, national and donor funding for newborn health has been low so far. Furthermore, kangaroo mother care, neonatal resuscitation, and antenatal corticosteroids all need coverage data to enable their scale-up to be tracked.

What next for Tanzania?

Mixed progress in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health in Tanzania indicates a complex interplay of political prioritisation, health financing, and consistent implementation. Post-2015, priorities for Tanzania should focus on the unmet need for family planning, especially in the Western and Lake regions; addressing gaps for coverage and quality of care at birth, especially in rural areas; and continuation of progress for child health.

What more can be done?

Why do you think Tanzania has made more progress for reducing child deaths beyond the newborn period, than for newborn or maternal deaths? What more do you think should be done now? What could your country learn from what Tanzania has done?

Share this

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free