History of Scotland: The Early Modern Period

The early modern period (c. 1500-1800) witnessed profound political, religious and social change in Scotland.

What began as an independent Catholic kingdom closely aligned with France ended as a stateless Protestant nation formally united with England. This dramatic shift was not a foregone conclusion but the result of a series of developments which occurred across the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Protestant Reformation

In the 1550s Scotland was ruled by the queen-mother Mary of Guise. She had been married to King James V until he died of illness in 1542. After a power struggle in Scotland she led a regency government in place of her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots. Due to her background and connections to the French Crown, in addition to Scotland’s historic relationship with France (‘the auld alliance’), leading positions in government were filled with Frenchmen. At the same time, ideas of reforming the Catholic Church increased in circulation. Grievances with Catholic corruption and French domination coalesced, and by 1559 the fiery preacher John Knox had returned from exile on the continent to lead the Protestant cause alongside the Lords of the Congregation. With the crucial military assistance of Protestant England led by Elizabeth I – cousin of the Queen of Scots – the Reformation was officially sanctioned by the Scottish Parliament in 1560. Thereafter Knox and his fellow evangelicals introduced a model of reform based on the experience of Geneva. In addition to changes in theology which denied intercessors other than Christ and rejection of the Catholic mass, rigid forms of governance and strict moral discipline were pursued. These required new forms of record keeping – innovations which produced accounts of local communities which were unparalleled in their detail.

Union of Crowns

Portrait of King James VI by the court painter Adrian Vanson [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of King James VI by the court painter Adrian Vanson [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Mary of Guise and her daughter’s husband, François II, both died in 1560. As a result, the Queen of Scots returned to rule Scotland. While prepared to tolerate Protestants she showed no inclination to convert herself. As had so often been the case during the medieval period, the Scottish nobility competed to control the young monarch. Her marriage choices, first to Lord Darnley and then the earl of Bothwell, stoked political rivalries. Mary’s marriage to Bothwell proved to be unpopular with most nobles and she was eventually forced to abdicate the crown in 1567 in favour of her son, James. Her Protestant half-brother, the earl of Moray, was then installed as regent. Following a brief civil war, Mary fled to England and was imprisoned. After her implication in a series of plots against Elizabeth she was tried in 1586 and executed in 1587. Her son, whose personal rule as James VI of Scotland had begun around 1584, became James I of England and Ireland after Elizabeth died without issue in 1603. James was great-great-grandson of Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch.

Covenants and Civil War

The Signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh (1838) by William Allan (1782–1850) [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The Signing of the National Covenant in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh (1838) by William Allan (1782–1850) [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

The second son of King James, Charles I, acceded to the throne in 1625. The style and substance of his government managed to alienate many of his subjects in the three kingdoms. In Scotland, distaste for his authoritarian drive for political, economic and religious uniformity with England, his sidelining of the traditional ruling elite, and his relegation of Scotland to provincial status within the Stuart imperium, led to protest, petitioning, and ultimately, the creation of the National Covenant in 1638. It was circulated throughout the localities and bound subscribers to defend the king provided he upheld ‘true religion, liberties and the laws of the kingdom’. The resistance of Scottish Covenanters led Charles to raise a Royalist army in England, but disaffection to his rule was also widespread south of the border. An alliance of Scottish Covenanters and English Parliamentarians was later consummated by the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. However, the alliance was sundered in 1649 when the English Parliament executed Charles I and the Scottish Parliament declared his son, Charles II, as king of Great Britain and Ireland. Following two demoralising defeats in battle, Scotland was incorporated into the English Commonwealth from 1652 until its collapse in 1660.

Restoration and Revolution

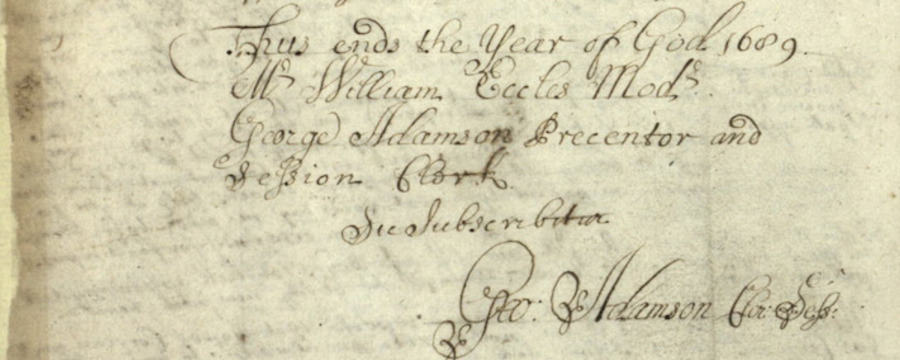

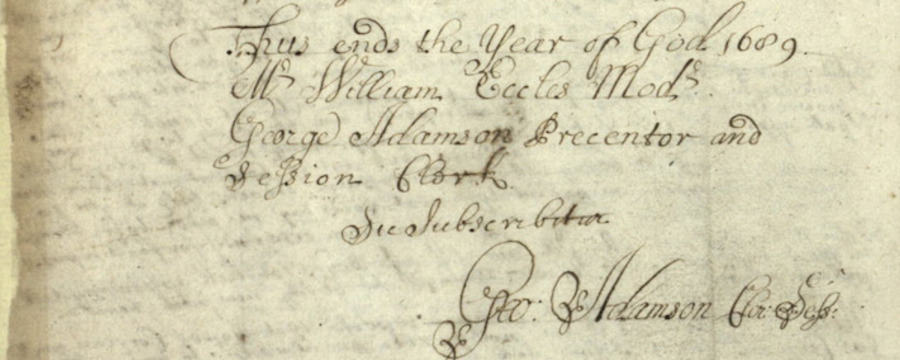

After two decades of upheaval, Charles II was restored to the three kingdoms in 1660. The constitutional settlement championed absolute monarchy as the necessary check against factionalism and rebellion. The restoration of bishops also saw around 200 Scottish Presbyterian ministers refuse conformity or else removed to restore the previous incumbents. They and their supporters led a campaign of dissent against the ruling regime. Nevertheless, Charles was able to see off concerted opposition in Scotland, England and Ireland until he suffered an apoplectic fit and died in 1685. He was succeeded by his Catholic brother, James VII and II, whose looming succession had been debated furiously from 1679 to 1681. While his reign began peacefully, it ended ignominiously with the so-called ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688-91, when Prince William of Orange and his wife, Mary – daughter of James – invaded England ostensibly upon invitation. Scottish and English exiles operating in the Netherlands returned with him. The revolution was promoted in Scotland by a Convention of Estates which met in 1689. It produced two documents, the Claim of Right and the Articles of Grievances, which proclaimed that James had ‘forefaulted’ the throne. The supporters of the exiled House of Stuart became known as Jacobites. Although their initial resistance was crushed by 1690, the Jacobites were involved in a series of plots and uprisings in 1708, 1715, 1719 and 1745.

Acts of Union

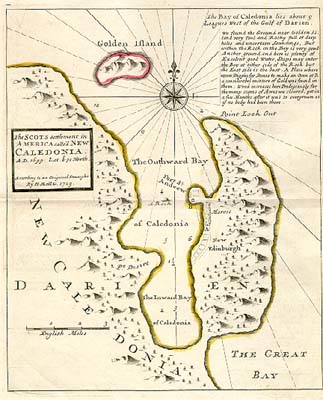

Map of the ill-fated Darien colony [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Map of the ill-fated Darien colony [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons

Following the death of William II and III in 1702, his sister-in-law and cousin, Anne, became Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland. However, her lack of heirs threatened a British succession crisis. In 1701 the English Parliament had nominated the House of Hanover as successors, while Louis XIV of France recognised the Jacobite heir as James VIII and III. With the Scottish Parliament refusing to settle on the Hanoverians and English recognition of the potential threat of a Franco-Scottish alliance, an unsuccessful attempt at Anglo-Scottish union was made in 1702-3. Indeed, the move from dynastic to parliamentary union was far from seamless: in addition to the short-lived Solemn League and Covenant, a series of abortive proposals were tabled across the seventeenth century. The failure of union in 1703 led to a legislative war which culminated with the Alien Act of 1705, whereby Scots in England were to be treated as aliens and aspects of Scottish trade embargoed unless the Hanoverian succession was recognised. By coercive persuasion, coupled with the impact of famine in the 1690s and the failure of the lone Scottish imperial venture at Darien on the Panama isthmus, the Scots returned to the negotiating table. Commissioners from both kingdoms discussed terms in 1706 and, despite widespread opposition, the treaty came into effect on 1 May 1707.

Empire and Enlightenment

Although the purported benefits of union were not felt until around 1750, the union gave Scots free access to the largest commercial market then available. Having previously circumvented the restrictions imposed by the English Navigation Acts through illicit trading, the Scots became enthusiastic participants in the British empire. In addition to commercial ventures, they also operated as colonial governors, administrators and military officers. Indeed, one of Scotland’s main exports was its people – particularly those with numeracy and literacy skills who could undertake colonial activities in demand such as accountancy and land surveying. As such, most Scottish adventurers came from educated gentry families who made extensive use of kin and business networks. However, the contribution of ideas was no less important, as the eighteenth century witnessed a ferment of intellectual and scientific achievement known as the Scottish Enlightenment. Largely the product of the Scottish education system, intellectual life revolved around clubs, societies and universities. Among many areas, Scottish thinkers made contributions to chemistry, engineering, medicine, philosophy, political economy and sociology. The practical application of new ideas also led to self-conscious agricultural ‘improvement’ as landowners sought to maximise the economic potential of their land. With economic growth, technical advancement and a shift towards manufacturing, the conditions were set for the rapid industrialisation of the nineteenth century.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free