The Impact of Domestic Violence and Abuse on Pregnancy

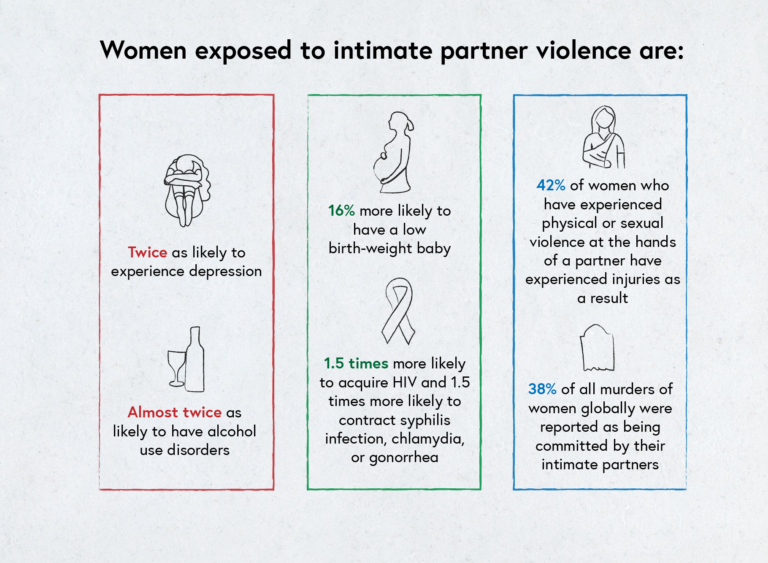

Adapted from a graphic produced by WHO based on a 2013 report entitled ‘Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence’ by the World Health Organization et al., 2013.

During pregnancy

Domestic violence and abuse (DVA) in pregnancy is linked to a wide range of negative outcomes.

In the extreme, DVA in childbearing can be a heightened risk factor for maternal death (McFarlane et al., 2002), along with homicide and suicide (Campbell et al., 2003). Women experiencing DVA during pregnancy are vulnerable to all the same mental and physical health issues that affect women generally (as depicted in the image above). Some of these effects have particular relevance and pose certain risks during pregnancy (as depicted in the image below).

In order to cope with the shame, stress and suffering caused by DVA, some pregnant women may self-medicate, or use tobacco, alcohol and other drugs (Campbell, 2002). Perpetrators of DVA during pregnancy may physically target the abdomen, causing several negative reproductive health outcomes (Bacchus et al., 2001; El Kady et al., 2005). At this time, perpetrators can also target the buttocks, breasts, genitals, head, neck and other extremities (Thananowan & Heidrich, 2008).

Select the image to expand it.

Pregnant people may also experience delays in their maternity care due to being prevented from leaving the house or missing appointments due to injury (Humphreys & Campbell, 2011).

There is an increased risk of miscarriage and abortion for those experiencing DVA during pregnancy (Fanslow et al., 2008; Pallitto et al., 2005). DVA during pregnancy also links to a variety of other negative reproductive outcomes such as intrauterine growth retardation along with preterm labour and birth, leading to low birth weight and other neonatal risks (Altarac & Strobino, 2002).

Other associated obstetric complications include an increased risk of haemorrhage and perinatal death (Janssen et al., 2003; Jejeebhoy, 1998).

The Janssen study involving a survey of over 4000 Canadians who gave birth between 1999 and 2000 did not find fear of a partner in the absence of physical violence to be associated with an elevated risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

A 2016 review drew together findings from 50 studies in one meta-analysis; it found a nearly two‐fold increase in the odds of delivering a preterm infant among victims of DVA during pregnancy, compared with women who were not exposed.

Similarly, the odds of low birth weight were doubled where DVA was present during pregnancy. The association with being small for gestational age was less pronounced and only marginally significant, although fewer studies were available for the meta‐analysis (Donovan et al., 2016).

After birth

The stress experienced by the victim of DVA during pregnancy can have long-term negative impacts upon the infant’s anxiety levels, along with their brain and behavioural development (Bergman et al., 2007; O’Connor et al., 2002).

All types of DVA during pregnancy (physical, sexual and psychological) have been associated with increased stress, depression, anxiety levels along with poor parental bonding, and lower rates of breastfeeding and suicide attempts (Caleyachetty et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2006; Zeitlin et al., 1999).

In a review of studies examining DVA and perinatal mental disorders by Howard and colleagues (2013), pooled estimates from longitudinal studies suggested a threefold increase in the odds of high levels of depressive symptoms in the postnatal period after having experienced DVA during pregnancy. Increased odds of having experienced DVA among women with high levels of depressive, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms in the antenatal and postnatal periods were consistently reported in cross-sectional studies. These findings invoke the literature on the relationship between postnatal depression and difficulties caring for a newborn baby and indeed the long-term problems associated with thwarted attachment between a mother and her child. Indeed, research has demonstrated how perpetrators target the bonding process between mother and child (Humphreys et al., 2006).

The continuance of abuse in the postnatal phase also marks the beginning of babies and young children being at risk of experiencing (formerly, the term ‘witnessing’) the abuse of their mothers and of becoming victims of child abuse.

Activity

How might this information about the impacts of domestic violence and abuse influence your practice in the future?

References

Altarac, M., & Strobino, D. (2002). Abuse during pregnancy and stress because of abuse during pregnancy and birthweight. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association (1972). 57(4), 208-214. Web link

Bacchus, L., Bewley, S., & Mezey, G. (2001). ‘Domestic violence in pregnancy’. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review. 12(4), 249-271. DOI link

Bergman, K., Sarkar, P., O’Connor, T. G., Modi, N., & Glover, V. (2007). Maternal stress during pregnancy predicts cognitive ability and fearfulness in infancy. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 46(11), 1454-1463. DOI link

Caleyachetty, R., Uthman, O. A., Bekele, H. N., Martin-Canavate, R., Marais, D., Coles, J., Steele, B., Uauy, R., & Koniz-Booher, P. (2019). Maternal exposure to intimate partner violence and breastfeeding practices in 51 low-income and middle-income countries: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS Medicine. 16(10), Article e1002921. DOI link

Campbell, J. C. (2002). Health consequences of intimate partner violence. The Lancet. 359(9314), 1331-1336. DOI link

Campbell, J. C., Webster, D., Koziol-McLain, J., Block, C., Campbell, D., Curry, M. A., Gary, F., Glass, N., McFarlane, J., Sachs, C., Sharps, P., Ulrich, Y., Wilt, S. A., Manganello, J., Xu, X., Schollenberger, J., Frye, V., & Laughon, K. (2003). Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health. 93(7), 1089-1097. DOI link

Donovan, B. M., Spracklen, C. N., Schweizer, M. L., Ryckman, K. K., & Saftlas, A. F. (2016). Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the risk for adverse infant outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 123(8), 1289-1299. DOI link

El Kady, D., Gilbert, W. M., Xing, G., & Smith, L. H. (2005). Maternal and neonatal outcomes of assaults during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 105(2), 357-363. DOI link

Fanslow, J., Silva, M., Whitehead, A., & Robinson, E. (2008). Pregnancy outcomes and intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 48(4), 391-397. DOI link

Howard, L. M., Oram, S., Galley, H., Trevillion, K., & Feder, G. (2013). Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 10(5), Article e1001452. DOI link

Humphreys, C., Mullender, A., Thiara, R., & Skamballis, A. (2006). ‘Talking to my mum’: Developing communication between mothers and children in the aftermath of domestic violence. Journal of Social Work. 6(1), 53-63. DOI link

Humphreys, J., & Campbell, J. C. (Eds.). (2011). Family violence and nursing practice. Springer Publishing Company.

Janssen, P. A., Holt, V. L., Sugg, N. K., Emanuel, I., Critchlow, C. M., & Henderson, A. D. (2003). Intimate partner violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population-based study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188(5), 1341-1347. DOI link

Jejeebhoy, S. J. (1998). Associations between wife-beating and fetal and infant death: Impressions from a survey in rural India. Studies in Family Planning, 300-308. DOI link

Martin, S. L., Li, Y., Casanueva, C., Harris-Britt, A., Kupper, L. L., & Cloutier, S. (2006). Intimate partner violence and women’s depression before and during pregnancy. Violence Against Women. 12(3), 221-239. DOI link

McFarlane, J., Campbell, J. C., Sharps, P., & Watson, K. (2002). Abuse during pregnancy and femicide: Urgent implications for women’s health. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 100(1), 27-36. DOI link

O’Connor, T. G., Heron, J., Golding, J., Beveridge, M., & Glover, V. (2002). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years: Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 180(6), 502-508. DOI link

Pallitto, C. C., Campbell, J. C., & O’Campo, P. (2005). Is intimate partner violence associated with unintended pregnancy? A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 6(3), 217-235. DOI link

Thananowan, N., & Heidrich, S. M. (2008). Intimate partner violence among pregnant Thai women. Violence Against Women. 14(5), 509-527. DOI link

World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, & South African Medical Research Council. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. Web link

Zeitlin, D., Dhanjal, T., & Colmsee, M. (1999). Maternal-foetal bonding: The impact of domestic violence on the bonding process between a mother and child. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2, 183-189. DOI link

Share this

Identifying and Responding to Domestic Violence and Abuse (DVA) in Pregnancy

Identifying and Responding to Domestic Violence and Abuse (DVA) in Pregnancy

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free