Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

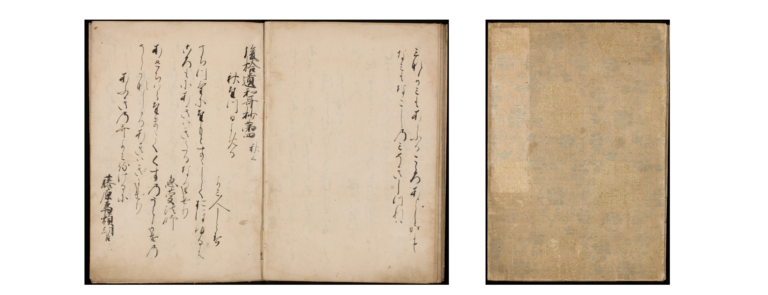

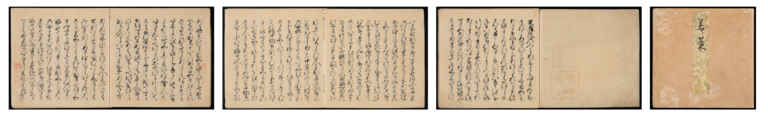

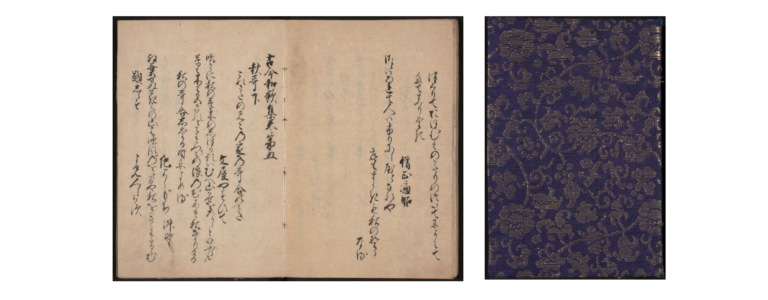

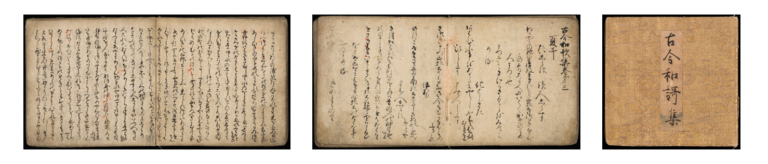

![Shimeisho [ca. 1289]](https://cdn-wordpress-info.futurelearn.com/info/wp-content/uploads/c1_s2_4_5-1-768x301.png)