Slave Rebellion in the Eighteenth Century: Tacky’s Revolt

An overwhelming preoccupation for white colonists was the possibility of a slave uprising. This concern was justified as there had been continuous conspiracies and attempts at rebellion since plantation economies began importing Africans as human chattel to be disposed of at the whim of White planters. Rebels faced severe punishment: torture, execution or being sold. Public displays of this violence served the colonial authorities to terrorise communities.

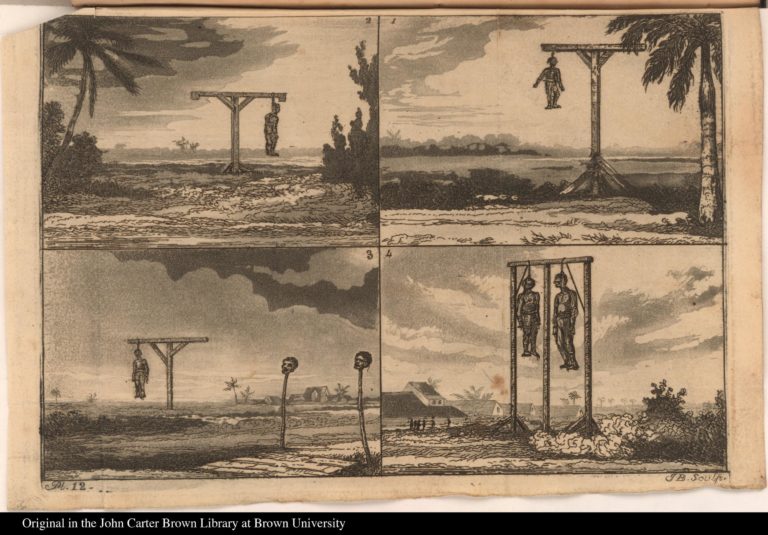

Warning: this image contains scenes of violence and death.

Joshua Bryant, Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. A. Stevenson At the Guiana Chronicle Office, Georgetown, 1824. Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library. This image shows the punishment inflicted on leaders of the 1823 Demerara revolt, a largely peaceful protest against worsening conditions in the British colony.

Joshua Bryant, Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. A. Stevenson At the Guiana Chronicle Office, Georgetown, 1824. Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library. This image shows the punishment inflicted on leaders of the 1823 Demerara revolt, a largely peaceful protest against worsening conditions in the British colony.

Once a neglected area of study, scholars of slave rebellions are providing new insights into this overt form of slave resistance. Eye-witness accounts, private correspondence, and historical military records, coupled with new cartographic analyses reveal that these slave revolts were a kind of African warfare; an outgrowth of (forced) migratory experiences but still an extension of those carried out in West/Central Africa before being captured and forced into Atlantic-based bondage. To illustrate how complex overt slave resistance can be, let’s consider the island-wide plot known as Tacky’s Revolt.

Tacky’s Revolt or Rebellion (1760-1761) is regarded as the most significant British Caribbean slave rebellion in the eighteenth century, and second only to the Haitian Revolution in comparative resistance. Although the actions of the principal rebel leader, Tacky, only lasted just over a week, his name is eponymously used to describe a series of battles, with several leaders, that last 18 months before the rebels were finally suppressed. This conflict was but a microcosm of intra- and inter-colonial turmoil as well as external imperialist expansions. An in-depth study of the causalities is beyond the scope of this learning step. This revolt was one front of a vast Atlantic war.

It began in Jamaica’s north-central parish, St. Mary, sometime after midnight on 8 April 1760. Tacky, said to have been a chief in Guinea, led 100 slaves to seize ammunition, guns, and powder from the unguarded Fort Haldane.

St. Mary Parish, Jamaica. Depicts location of parish in north-central portion of island. Public domain. Source: Wikipedia.org

St. Mary Parish, Jamaica. Depicts location of parish in north-central portion of island. Public domain. Source: Wikipedia.org

It quickly spread across the countryside to Westmoreland and Hanover Parishes by the following month. Bands of rebels rose up in other parishes such as Clarendon, St. Elizabeth, and St. James. Along the way, sadistic overseers were killed, and plantation crops were destroyed. However, the most affected areas of rebellion were St. Mary’s and Westmoreland with African insurgent numbers exceeding 1000.

According to colonial administrator, slaveholder, and historian Edward Long, Tacky and his followers planned to wipe out the entire white population. If any Blacks refused to join the cause, then they would be enslaved. After which, the island would be a new West African state, partitioned into small principalities under the leadership of chosen men.

The British militia’s initial reaction to the insurrection was not successful. In fear, White families left their estates and fled to port towns. Situations were only made worse due to panic and confusion. Historians suggest that the rebellion was not a convoluted and haphazard set of incidents favoured by luck as African rebels, many of whom were soldiers of war on the African continent exercised military expertise. Moreover, they easily found safety and camouflage in the dense mountainous forests.

The militia were unfamiliar and unaccustomed to such terrain and were therefore ill-equipped to respond to co-ordinated tactics of guerrilla warfare (i.e., booby traps, ambushes, quick but deadly skirmishes). Furthermore, many of these attacks were planned to occur when the British Navy, already struggling with a dwindling fleet size because of the Seven Years War, would leave to escort sugar convoys to Britain. This left the island with significantly reduced militias for defence.

As the fear that African rebels could very possibly take control of Jamaica took hold of the White island population, Lieutenant Governor Henry Moore changed tactics and issued a formal counterinsurgency. He declared martial law with impunity to torture and kill any Black person deemed questionable and secured assistance from the Army and the Navy. Over the course of 18 months, 60 Whites were killed and thousands of pounds worth of property destroyed. Over 500 Black men and women were killed in battle, committed suicide or executed after British military suppressed the revolt. Another 500 were forcibly removed from Jamaica and deported to Nova Scotia.

It’s still unknown if Tacky, the principal leader in the initial attack in St. Mary parish, was the mastermind for all proceeding attacks. But what is clear is the wave of destruction and battles that spread across the island were led by Coromantee1 Africans, that included Apongo (later known as Wager), Simon, and most likely, several others with experience in African warfare from the continent.

What’s interesting is that planters purposely chose to import so many African captives from the Gold Coast region because they prized their agricultural skills. However, as many were also experienced soldiers and military strategists they were able to organise highly successful revolts, which could only be suppressed with overwhelming use of force.

Revolts continued throughout the period of slavery. In 1823, for example, enslaved people revolted in the colony of Demerara. A dip in the price of sugar in the early 1820s resulted in enslavers enforcing even more punishing work schedules. When proposals to improve the conditions on the plantations were postponed by the Governor of Demerara, 9,000 enslaved people launched an attack.

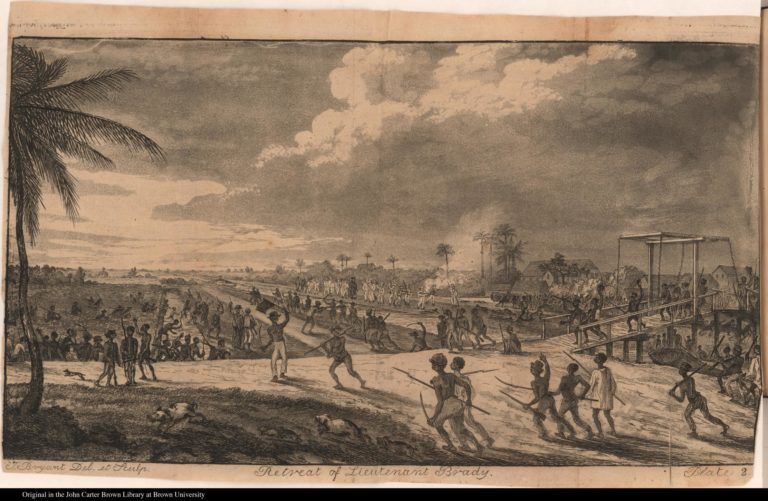

Joshua Bryant, Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. A. Stevenson At the Guiana Chronicle Office, Georgetown, 1824. Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library.

Joshua Bryant, Account of an insurrection of the negro slaves in the colony of Demerara, which broke out on the 18th of August, 1823. A. Stevenson At the Guiana Chronicle Office, Georgetown, 1824. Courtesy of John Carter Brown Library.

Enslavers and British colonial authorities found it difficult to believe that enslaved people could be organised and determined enough to drive back British troops. They blamed John Smith, a British minister who ran a local chapel. He was arrested and died in prison before his pardon arrived. The real leader of the revolt, Jack Gladstone, and his father Quamina, were captured by Captain Michael McTurk (a medical graduate of the University of Glasgow). Quamina was executed, while Jack was sold and forcibly transported to St Lucia.

1Coromantee was a term the British projected upon enslaved Africans sold through the British fort of Kromantine, though these Africans were from a range of ethnic groups in the Gold Coast interior of present-day Ghana.

Further reading

The foremost authority on Tacky’s Revolt is Dr. Vincent Brown, Charles Warren Professor of History, Professor of African and African-American Studies at Harvard University. His cartographic project, ‘Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760-1761: A Cartographic Narrative’, uses an interactive map and allows you to track the daring ingenuity of Tacky’s movements within the spatial dimensions of Jamaica’s landscape.

Or read: Vincent Brown, Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War, published by Harvard University Press, 2020.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free