Sexology and the ‘Invention’ of Homosexuality

Dr Tanya Cheadle

The confession, by Pietro Longhi, ca. 1750. Public domain

The confession, by Pietro Longhi, ca. 1750. Public domain

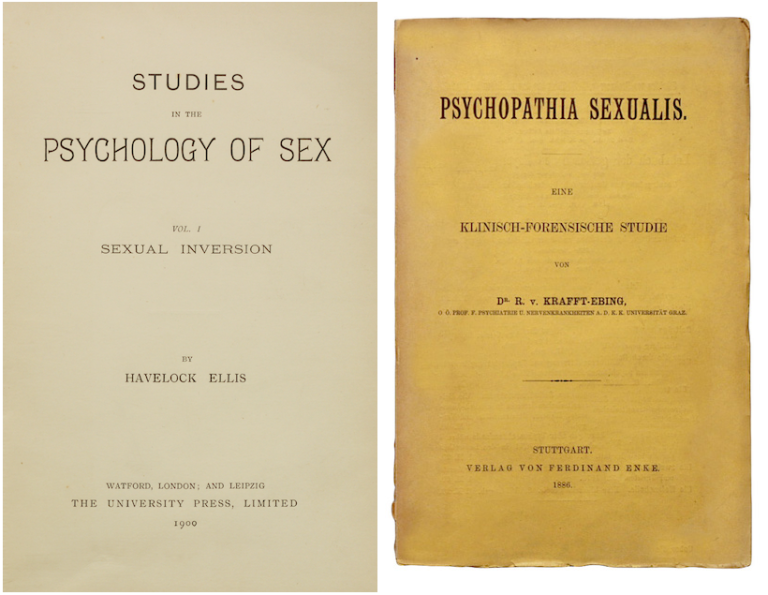

In pre-modern societies, the work of interpreting and regulating sexual behaviour fell primarily to clergy, moralists and lawyers, who in the confessional box and the courtroom alike determined the boundaries of what was deemed possible and permissible. Around the end of the nineteenth century however, a new scientific discipline emerged in Europe and America concerned with the study of human sexual behaviour. Coined ‘sexology’ in 1902, it encompassed those working in a range of fields, including anthropology, biology, psychology and psychiatry. Together, its practitioners aimed to provide a comprehensive classification of human sexuality, often by accumulating autobiographical case studies of sexual desire and behaviour. Important early texts include Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) by Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Sexual Inversion (1897) by the English physician Havelock Ellis, with the field introducing many terms still in use today, such as homosexuality, heterosexuality, sadism and masochism.

Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 1: Sexual Inversion (1900) and Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis (1886)

Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 1: Sexual Inversion (1900) and Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis (1886)

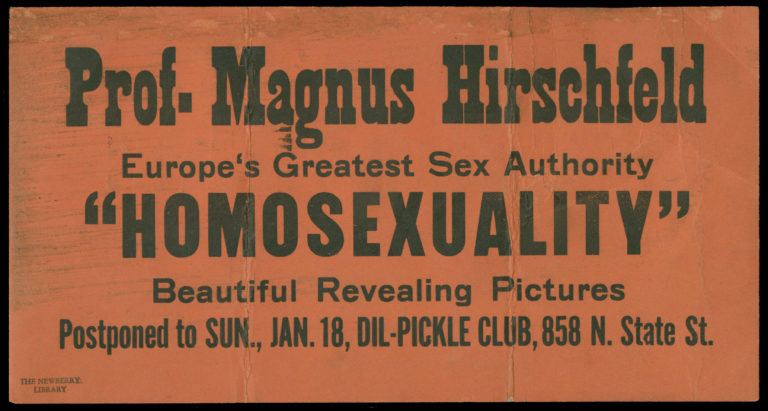

Sexology’s status and influence varied markedly in different countries, with theorists often marginal and sometimes progressive figures. In Germany and Austria, for example, the discipline was associated with sexual reform movements. In 1897, Austrian Magnus Hirshfeld co-founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee to campaign for the reform of the German penal code which punished male same-sex relations and on a lecture tour in the US in 1930 was heralded as the ‘Einstein of Sex’. One of the earliest sexological writers was the German lawyer Karl Heinrich Ulrich, who considered himself an ‘urning’, his term for a man with a female soul in a male body.

Advertisement for a lecture in Chicago on ‘Homosexuality’ by Magnus Hirshfeld (1931). Public domain

Advertisement for a lecture in Chicago on ‘Homosexuality’ by Magnus Hirshfeld (1931). Public domain

As Ulrich’s use of nomenclature suggests, a key concept of sexology was that of ‘sexual inversion’, in which same-sex relations were interpreted through the prism of gender. Lesbians were therefore understood as ‘mannish’ and gay men as ‘effeminate’. Krafft-Ebing, for example, when writing about gay men in Psychopathia Sexualis, asserted that ‘feminine timidity, frivolity, obstinacy and weakness of character rule among such individuals’ while ‘uranism may be suspected in females wearing their hair short, or who dress in the fashion of men, or pursue the sports and pastimes of their male acquaintances.’ While Krafft-Ebing initially pathologized same-sex sexuality, seeing it as unnatural, he later changed his view, in part because of his interactions with happy homosexual couples, concluding in 1965 such relationships ‘may proceed with the same harmony and satisfying influence as in the normally disposed.’

Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park (1869). Public domain.

Thomas Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park (1869). Public domain.

Historians’ views on sexology’s influence on society have shifted over time. While the field was seen by early scholars, such as Ronald Pearson, as liberating society from the ‘debilitating disease’ of Victorian morality, the publication of the first volume of Foucault’s The History of Sex in 1976 rendered such interpretations problematic. Instead, argues Chris Waters, historians were more likely ‘to view sexologists as insidious agents of social control whose work functioned to discipline subjects by stigmatizing non-normative desires as deviant and by reinforcing patriarchal, heterosexual norms’ (Waters 2006, p. 54).

More recently, scholarship has focused both on how sexological studies were produced and how they were interpreted and reappropriated by their subjects. Harry Oosterhuis has argued that Krafft-Ebing drew on his correspondence with his middle- and upper-class patients when formulating his theories, while his publication of their uncensored case histories allowed room for readers to find their own resonances in such accounts, distinct from medical diagnoses. As Oosterhuis writes, in Krafft-Ebing, his patients and correspondence found ‘not simply a doctor treating diseases, but someone who answered their need to have themselves explained to themselves, an emotional confident and even an ally’ (Oosterhuis 2000, p. 199). One thirty-eight-year old ‘urning’ told Krafft-Ebing ‘I am very unhappy with my condition and have often considered suicide, but I was somewhat reassured after reading the Psychopathia Sexualis’, while another wrote how the work had given him ‘much comfort’:

‘It contains passages that I might have written myself; they seem to be unconsciously taken from my own life. My heart has been considerably lightened since I learned from your book of your benevolent interest in our disreputable class. It was the first time that I met someone who showed me that we are not entirely as bad as we are usually portrayed … Anyway, I feel a great burden has been lifted from me.’

Radclyffe Hall (right) and Una Troubridge with their dachshcunds at Crufts dog show, February 1923

Radclyffe Hall (right) and Una Troubridge with their dachshcunds at Crufts dog show, February 1923

Perhaps the most celebrated example of the impact of sexology on the emergence of homosexual identities is Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness (1928). The moment of self-discovery for the book’s protagonist Stephen Gordon comes when she reads her dead father’s marginalia in a sexological work:

‘Then she noticed that on a shelf near the bottom was a row of books standing behind the others; the next moment she had one of these in her hand, and was looking at the name of the author: Krafft Ebing – she had never heard of that author before. All the same she opened the battered old book, then she looked more closely, for there on its margins were notes in her father’s small, scholarly hand and she saw her own name appeared in those notes – She began to read, sitting down rather abruptly.’

Further Reading

Harry Oosterhuis, Stepchildren of Nature: Krafft-Ebing, psychiatry and the making of sexual identity (University of Chicago Press, 2000)

Merl Storr, ‘Transformations: Subjects, Categories and Cures in Krafft-Ebing’s Sexology’, in Lucy Bland and Laura Doan (eds), Sexology in Culture: labelling Bodies and Desires (Polity Press, 1998), pp. 11-26

Chris Waters, ‘Sexology’ in H.G. Cocks and Matt Houlrook (eds), Palgrave Advances in the Modern History of Sexuality (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), pp. 41-63

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free