How cultural feminism challenged social roles that were based on gender

Share this step

The term ‘Cultural Feminism’ emerged in the early 1970s amidst the women’s liberation movement, and championed a range of political aims, critical platforms and approaches. Its advocates problematised the cultural constructions and representations of gender identities that allocate distinct social roles on the basis of sexual difference, and saw these as the root cause of women’s oppression.

As part of the wider feminist movement at the time, cultural feminist initiatives were aimed at questioning dominant gender norms and institutions, focusing primarily on everyday life, the family, the body and sexuality. Broadly speaking, cultural feminists believed and believe that it is only by destroying deeply-seated cultural norms and representations of ‘the feminine’ and ‘the masculine’, that women (and men) can be liberated.

In this view, the bettering of women’s political and economic status hinges not only on legal or economic change and formal equality, but on a much deeper cultural transformation.

Spaces for women only

An important practice for cultural feminists since the 1970s was the creation of women-only spaces (collectives, bookshops, art workshops, for example), where they attempted to generate a new, patriarchy-free consciousness and engage in radically different ways of living.

The feminist theorist Mary Daly described the burgeoning of an alternative consciousness as “a spring into free space” (1978). Women initiated their own versions of the following:

- Publishing collectives (e.g., the Feminist Press at City University, New York, est. 1970)

- Feminist periodicals and magazines (e.g., Spare Rib in the UK, est. 1972)

- Feminist bookstores (e.g., Libreria delle donne, Women’s Library, established in Milan in 1975, Sisterwrite in London, est. 1978, and Womanzone, Edinburgh, est. 1983)

- Non-profit organisations, soup kitchens, and intentional communities (e.g., the various lesbian-separatist ‘womyn’s land’ communities created in the US and Australia)

As diverse as these endeavours were, they shared the belief that patriarchy would be destroyed through the creation of countercultural, alternative spaces, and by developing new living practices, rejecting normative gender roles.

The creation of women-centres and platforms was also motivated by the need for spaces that were safe and free from patriarchal violence.

Powerful feminist intervention

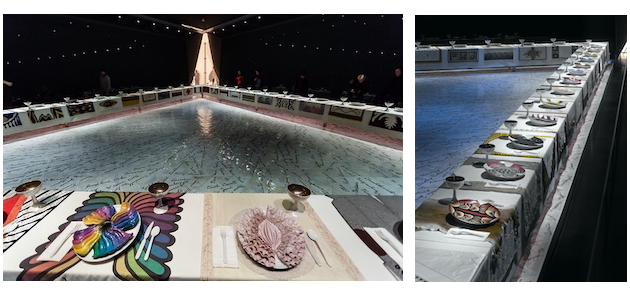

One seminal expression of feminist culture and art, which resonates to this day, is Judy Chicago’s art installation The Dinner Party (1974-79) — pictured below — which is now permanently housed at the Brooklyn Museum.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party. Photo: Kevin Case. Creative Commons

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party. Photo: Kevin Case. Creative Commons

It offered a powerful feminist intervention into wider public discourse of gender, culture and art, and has served as a point of reference for feminist artists ever since.

Chicago’s multi-media installation featured a large triangular table covered with an embroidered tablecloth, plus 39 ceramic place settings (13 per side) in the shape of organic forms and alluding to female anatomy, as well as cutlery and chalices.

Each setting commemorated a historical woman. The names of a further 999 female saints, rulers, political activists and artists were inscribed on the white-tiled floor on which the table was placed.

Chicago’s artwork was based on her research into women’s history, and one of her key concerns was to reclaim the work of women who had been hidden from history.

Chicago was keen to find out “whether women before me had faced and recorded their efforts to surmount obstacles similar to those I was encountering as women. When I started my investigation, there were no women’s studies courses” (Chicago quoted in Perry, 1999).

Controversy

Her installation was greeted by a storm of controversy when first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco in 1979. Established artists and critics were critical of Chicago’s exclusive celebration of women and uncomfortable with her overt sexual imagery.

While some considered the work to be pornographic, feminist reviewers worried that her overt sexual imagery could be appropriated by the male gaze/pleasure. But Chicago ultimately succeeded in drawing attention to the elimination of women from conventional historical narratives, whilst contributing to a new cultural-feminist language and community.

For some feminists, the creation of women-centred spaces was also about bringing to the surface and exploring women’s identity. The creation of a new, anti-patriarchal culture would be based on what they saw as female characteristics, such as nurture and pacifism.

In Women and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her (1978), for example, Susan Griffin argued that women were more closely bonded with nature than men and should therefore be taxed with reverting pending ecological disaster. For others, these were dangerously essentialist approaches which failed to question the very category of ‘woman’, and could lead to the de-politicisation of the radical-feminist agenda, as argued for instance by cultural historian Alice Echols (Echols, 1989).

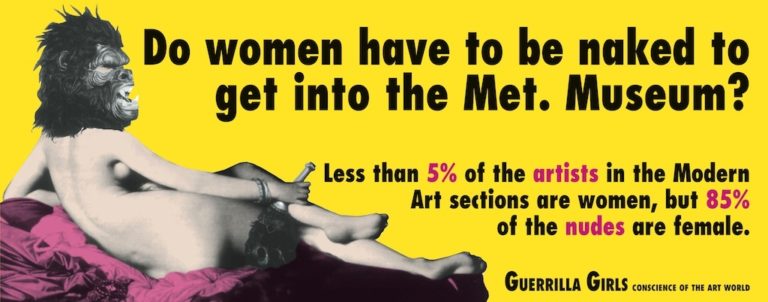

Guerrilla Girls. Copyright: St Larence University Gallery. Creative Commons.

Guerrilla Girls. Copyright: St Larence University Gallery. Creative Commons.

Political messages

Despite these critiques, feminist artistic expression has in recent decades proven capable of articulating powerful political messages and projecting visions of the transformation of not only representations of womanhood, but of society at large.

To take but one example, Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of artists and activists, started disrupting cultural events and institutions in New York in the mid-1980s. Since then, their practice of ‘jamming’ – subverting the messages of established cultural institutions such as museums through direct action – has been applied by feminists around the world, aiming to draw the public’s attention to the patriarchal structures of cultural production, and the sexist and racist content of mainstream culture.

Contributors: Dr Sabine Wieber and Dr Maud Anne Bracke, both from University of Glasgow

- Listen to Alice Echols, author of the ground-breaking book Daring to Be Bad, talk about about the rise and fall of radical feminism in the pivotal year of 1968 here.

References

Daly, Mary (1978) Gyn/Ecology (Beacon Press).

Echols, Alice (1989) Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 (University of Minnesota Press).

Forster, Laurel, ‘Spreading the Word: feminist print cultures and the Women’s Liberation Movement’, Women’s History Review, 2016, 25:5, pp. 812-831.

Griffin, Susan (1978) Women and Nature: The Roaring inside Her (The Women’s Press).

Lucy-Smith, Edward, Judy Chicago (2000) Judy Chicago: An American vision (Watson-Guptill Publ.)

Mullins, Charlotte (2019) A Little Feminist History of Art (H. N. Abrams Publ.).

Perry, Gillian (1999) Gender and Art (Yale University Press).

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free