Peace in Colombia: What Are the Challenges?

Share this step

SDG 16 emphasises that both promoting peaceful and inclusive societies, and ensuring accountable, inclusive, and transparent institutions are central to sustainable development.

In light of this goal, we are going to look at the case study of the recently signed Colombian peace accords between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP) and the Colombian government. This is an interesting case study as it looks at how a country addresses transitioning to peace by reintegrating groups involved in conflict. It also highlights the importance of inclusive institutions to maintain peace.

In this case, the Colombian peace accords contain many provisions that seek to ensure peace through just institutions, but many challenges remain.

Challenges to achieving peace in Colombia

Colombia is a middle-income country in South America which has experienced relatively steady economic growth and human development. But alongside this development, over 50 years of internal conflict has had devastating effects on the country: claiming more than 220,000, mostly civilian lives, and victimising more than 7.9 million people (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz, 2016). The conflict has mainly had an impact on poor rural regions where left-wing guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitaries, and the Colombian state army “fight a war with class dimensions” (Cockburn, 2007: 13).

This conflict has been attributed to many problems and challenges, for example:

- Extreme levels of wealth disparity

- A very high concentration of landownership

- Competition for control of natural resources

- A weak and corrupt state

Such problems are worsened by international state actors, multinational corporations, narco-trafficking, and criminal gangs. There have also been widespread human rights violations.

The peace accords

After four years of negotiations, which began in 2012, the Colombian peace accords were signed in November 2016. A first version was narrowly defeated in a national referendum the month previously. This final second version of the accords was published after consultation with opposition and other groups, and was ratified through the Colombian National Congress.

The Colombian peace accords have been praised for their inclusive language and various approaches to, and conception of, peace. The agreement will attempt to correct many of the injustices at the root cause of the conflict rather than only focusing on stopping direct violence. For example:

- A land restitution programme, which considers the millions of internally displaced people in Colombia

- New approaches to combating the issue of illegal drugs

- Extensive promises of rural development to end the extreme poverty and inequality seen in the Colombian countryside

- Increased political, social, and economic participation of the country’s most marginalised people (Herbolzheimer, 2016)

Reintegrating FARC-EP members into societal and political life

A key part of the peace process is reintegrating FARC-EP members into society. Today, there are approximately 7,000 FARC-EP members in 26 “Transitory Standardization Zones” (ZVTN) throughout the country. Here, FARC-EP members are preparing for reintegration back into civilian life.

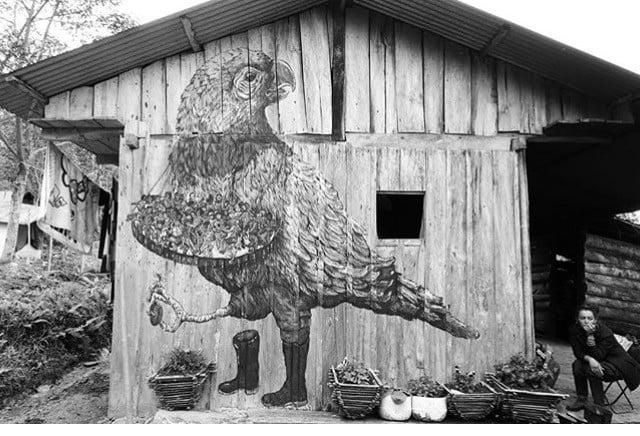

The entrance to the FARC-EP demobilisation camp near Icononzo, Colombia. The sign reads “Territory for reconciliation through the construction of peace with social justice”. © Chiara Mizzoni

The entrance to the FARC-EP demobilisation camp near Icononzo, Colombia. The sign reads “Territory for reconciliation through the construction of peace with social justice”. © Chiara Mizzoni

Reintegration programmes are believed to be vital to stopping conflict and ensuring peace, and a failure to do so could lead to conflict resurgence. Both the government and FARC-EP need to be committed to this long-term process which will include benefits such as economic and educational assistance.

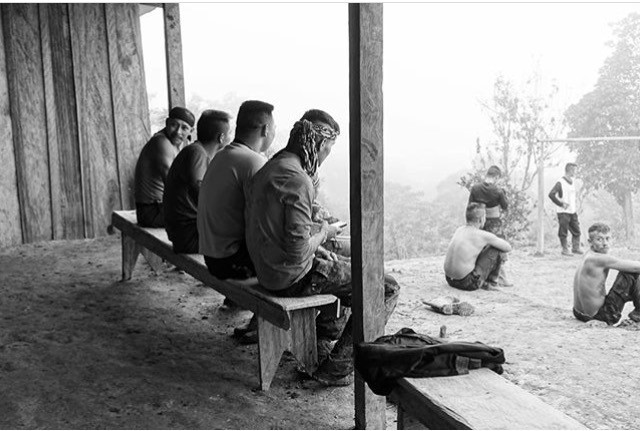

Members of FARC watch a game of afternoon football at the Icononzo camp. © Chiara Mizzoni

Members of FARC watch a game of afternoon football at the Icononzo camp. © Chiara Mizzoni

The peace accords also guarantee the fair and safe participation of FARC-EP in political life as an established political party after this phase. Given the large sectors of society who remain on the fringes of Colombia’s political process, the peace accords aim to deepen democracy in Colombia. The agreement aims to do this by improving citizen participation and creating space for political opposition groups, dissidents, and new movements which may emerge post-conflict.

Transitional justice

An important part of the peace process is what is known as transitional justice. This is a term used to talk about how countries emerging from conflict address human rights abuses. In Colombia, transitional justice is generally viewed as having three key elements: truth, justice, and reparation. The peace agreement creates an innovative transitional justice framework which includes two mechanisms: a Justice Tribunal and a Truth Commission.

- The Justice Tribunal will investigate, try, and sentence those involved in the conflict.

- The Truth Commission will seek to explain the conflict and ensure non-repetition.

Through the application of an amnesty law (for those cleared of crimes against humanity), sentencing will include restricted liberties and work on community projects. A victim’s fund, alongside a land fund, will compensate victims.

The challenge of unjust institutions

Colombia already has strong legislation in place to protect the rights of victims, women, minority groups, and indeed all citizens.

There is however, a clear gap between policy and implementation.

- Delays in the construction of the demobilisation camps

- The lack of a detailed roadmap on collective reintegration

- Ongoing violence against community leaders

- Power vacuums not being adequately filled by the state in areas where FARC-EP have withdrawn, but other non-state armed actors seek new territory

The future for peace in Colombia

For peace and therefore sustainable development to flourish in Colombia, certain societal structural inequalities must be addressed, and it is positive that the accords acknowledge this.

But a real commitment to justice for victims, the successful reintegration of FARC-EP, as well as the sustained political and social will to ensure the successful implementation of all aspects of the peace accords are needed. Only then will the aspirations of SDG 16 be realised in Colombia.

- What other SDGs do you think are challenged by the transitional peace process in Colombia? You can take a look at this download to remind you of the 17 SDGs.

Chiara Mizzoni is a PhD Researcher in the Irish School of Ecumenics at Trinity College Dublin. As part of her research she is exploring Colombia’s DDR (Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration) programmes from a gender perspective.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free