Malnutrition and HIV

Share this step

One of the reasons that malnutrition is such a big public health problem is that it interacts with other health challenges. One of these is the HIV epidemic. Since the start of the epidemic an estimated 78 million people have become infected with HIV, and 35 million people have died of AIDS-related illnesses. Malnutrition and the HIV epidemic are intertwined in many ways, in particular in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2015, an estimated 36.7 million people were living with HIV (including 1.8 million children). The vast majority of these people live in low- and middle-income countries, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although many countries have responded well to the crisis, still around 40% of all people living with HIV do not even know that they have the virus.

Advances in HIV treatment

HIV is treated with a combination of antiretroviral drugs or ARVs. Although scientists are working to develop a vaccine there is none available at present, and so to remain well a person with the disease needs to take their ARVs every day.

Donor organisations have made controlling HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa a priority. The US President’s Emergency Plans for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) is one of the best-known global programmes to tackle HIV. PEPFAR is currently supporting 11.5 million people to access antiretroviral drugs. The programme has saved many lives and prevented millions more HIV infections.

Through programmes such as PEPFAR we have also learned important new ways of preventing infection. For example, by treating mothers in pregnancy we can reduce mother to child transmission of HIV to about 1%. There is also compelling evidence that male circumcision reduces the risk of heterosexual transmission of HIV infection in men by approximately 60%. So theoretically, we have the tools and political will, if not to cure the disease, to at least control the HIV pandemic and make HIV a chronic and treatable disease rather than a death sentence.

Why then does HIV remain such a devastating disease in the global south?

To understand this better, let’s look at what life is like for two people living with HIV: one in Europe and one in Sub-Saharan Africa.

| Robert is 42 years old and is a homosexual teacher living in Dublin. He was diagnosed as part of a routine sexual health check and started on treatment before he had any symptoms. His HIV is well controlled; his immune system works normally to fight infections, and he uses condoms to prevent infecting others. He has a chronic but manageable disease. His main concern is the side-effects of his medication which have caused his cholesterol to rise and some weight gain, he also has mild diabetes. His life expectancy has increased by about 10–15 years since the drugs were introduced in the mid 1990s. His current partner is in his 60s and also has the disease. |  |

Compare this with Sarah, you will be meeting her again in Week 4.

| Sarah is 40 years old and lives in rural Uganda. She is the mother of 3 boys and was infected by her husband. After he died, she developed symptoms of infection and weight loss; she couldn’t continue working to pay school fees or buy food. A local community health worker advised her to get tested. In the beginning, she needed treatment for TB as well as HIV but she is starting to recover and is regaining her strength slowly. She had to move away from the area she was living in to be nearer her family. She needs to return to work soon; she is managing on food handouts from family and the clinic to buy necessities. The life expectancy of a women like Sarah living with HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa has also increased but by only by about 7–10 years since the introduction of ARVs. |  |

As you can see from these two case studies, while the drugs are an important part of the treatment, it is critical that patients remain engaged in care to manage the long-term effects of the disease and its treatment and to prevent infection in others. No matter their location, it’s essential that people living with HIV have easy access to HIV diagnosis, and ongoing access to medication and treatment as needed. If they do not take their medication regularly as prescribed, they will continue to experience ill health.

A range of factors can affect access including infrastructure, such as transport to a health clinic, and working patterns. In the case of casual or mobile workers (such as those engaged in the informal economy or those commuting long distances to find casual or seasonal work) it can be much more difficult to consistently manage the disease. Thus the wider environment impacts the disease. We will see how availability of food and adequate nutrition is part of this picture.

HIV and malnutrition

HIV and malnutrition are linked in many ways including:

- Poverty

- Food insecurity

- Physiologically and immunologically

Fundamentally, poverty and food insecurity increase the risk of becoming infected with HIV. People living in poverty are more likely to engage in risky behaviour, such as transactional sex to maintain their food supply. They are also less likely to access adequate health services to manage the disease. Importantly, the presence of malnutrition as well as HIV decreases the effectiveness of anti-HIV drugs and increases the chances of adverse drug effects. Even when HIV treatment is successful, good nutrition is still an important factor in helping people to manage their disease and return to their normal activities.

The NOURISH project

There are many reports on HIV and on the problem of nutrition, but actually very few studies that look at how all these factors interact together, which would help us understand contributors to the success or failure of healthcare programmes. The NOURISH project is a collaboration between researchers in Ireland and Uganda, and aims to do just that. NOURISH researchers sought to understand more about the links between nutrition and health, particularly in the case of people living with HIV. As mentioned above, malnutrition can complicate the treatment of HIV. Patients who are severely malnourished will not be able to adequately process ARV drugs.

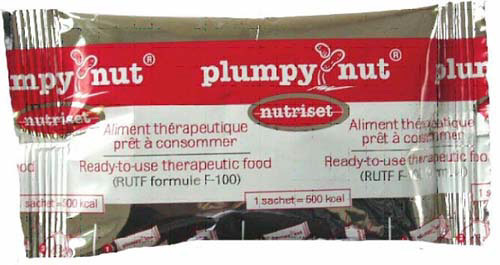

A supplement called Plumpy’nut is given to these patients as they start treatment with ARVs. This is to improve their nutritional status and help them benefit from the drugs. Plumpy’nut is a bit like peanut butter.

NOURISH researchers examined the impact of providing Plumpy’nut to a group of 250 adults and children diagnosed with HIV, and starting on ARVs. These adults and children were experiencing differing degrees of malnutrition and were categorised as severely or moderately malnourished, or well-nourished based on their BMIs when they first attended a HIV clinic.

Researchers asked patients to consume two sachets a day of Plumpy’nut for 12 weeks, which provided them with an additional 1000 calories a day. They found this was beneficial to those patients who were severely malnourished, helping them to gain weight and more effectively process their medication. These patients also showed an increase in a protective type of cholesterol called HDL, bringing health benefits. However, the patients who were moderately malnourished did not show the same benefits.

This type of study can help policymakers in Uganda when they are considering how best to help people living with multiple health conditions, in this case HIV and malnutrition.

NOURISH researchers in the field

NOURISH researchers in the field

What is a sustainable solution for people living with HIV, malnutrition, and poverty?

Policymakers must decide how best to spend a country’s available budget to help those dealing with multiple health challenges. It’s important that these decisions are based on the best evidence about whether an intervention works for everyone or does not. This is where researchers can help. Since food security and malnutrition are major challenges to achieving SDG 3, we need to think about interventions to assist people living with poverty, malnutrition, and HIV that are more cost-effective and sustainable.

While Plumpy’nut can be beneficial, it is relatively expensive. NOURISH researchers were interested in finding a more cost-effective way of improving nutrition for women living with HIV. Researchers developed a homemade and nutritious food recipe, and used local ingredients to tailor this food product to each of the four regions in Uganda. The researchers then tested the impact of an information campaign, demonstration of the recipe, and female empowerment intervention, to see if these attempts could improve the health and well-being of women attending HIV clinics across Uganda.

During Week 4 you will learn more about what they found.

- Thinking about Robert in Ireland and Sarah in Uganda, what challenges do they face in their treatment and management of HIV?

- Are they similar or different?

- Why/why not?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free