The Challenges of Interpretation at Saugus Iron Works

The text below was kindly written by Dr Emily Murphy, Curator of Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site. It is included here with her permission and courtesy of the US National Park Service.

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site is a reconstruction of the Hammersmith iron works, which operated between 1646 and about 1670. Originally, the site encompassed about 600 acres, including areas for workers’ housing, a large farm, a pond and waterways to power the works. It was the first integrated iron works in north America, consisting of a blast furnace that produced cast iron as well as pig iron, a forge where the pigs were melted again and pounded into wrought iron bars, and a rolling and slitting mill that could then turn the bars into nail rod and thinner stock for making wheel rims, among other products. Through a combination of bad management and dwindling supply, the iron works was out of business by the end of the 1670s. Today, Saugus Iron Works NHS consists of nine acres surrounding the industrial buildings reconstructed on the original foundations.

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site as it appears today. Courtesy US National Park Service.

Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site as it appears today. Courtesy US National Park Service.

Interpretation of the Scots prisoners at Saugus has evolved over the years. Between 1948 and 1953, The American Iron and Steel Institute financed the First Iron Works Association, which paid archaeologist Roland Robbins to excavate the industrial buildings at Saugus so they could be reconstructed. As part of the project, Massachusetts Institute of Technology history professor Edwin H. Hartley researched the Iron Works, and in 1957 published Iron Works on the Saugus. This book reflects AISI’s focus on the technology, and mainly brings up the Scots in relation to the cost of their maintenance.

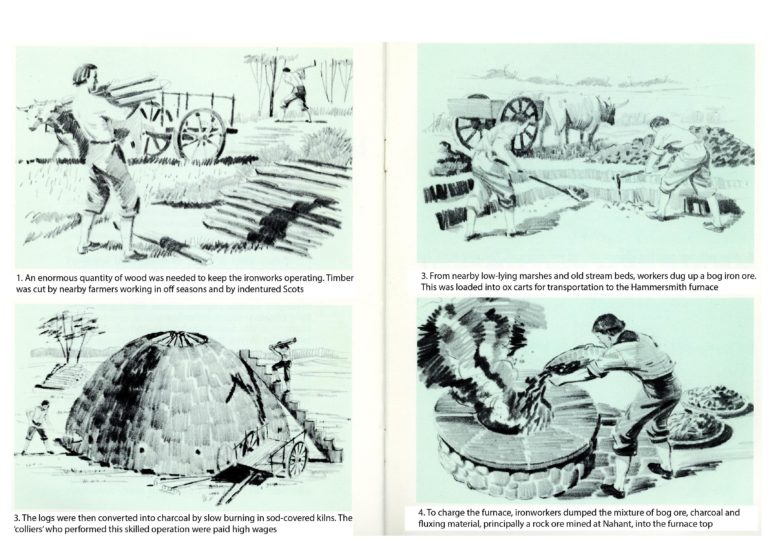

‘How iron was made at Hammersmith’, from the 1953 guidebook ‘The First Iron Works Restoration’. Courtesy US National Park Service. 1 An enormous quantity of wood was needed to keep the ironworks operating. Timber was cut by nearby farmers working in off seasons and by indentured Scots. 2 The logs were then converted into charcoal by slow burning in sod-covered kilns. The ‘colliers’ who performed this skilled operation were paid high wages. 3 From nearby low-lying marshes and old stream beds, workers dug up a bog iron ore. This was loaded into ox carts for transportation to the Hammersmith furnace. 4 To charge the furnace, ironworkers dumped the mixture of bog ore, charcoal and fluxing material, principally a rock ore mined at Nahant, into the furnace top.

‘How iron was made at Hammersmith’, from the 1953 guidebook ‘The First Iron Works Restoration’. Courtesy US National Park Service. 1 An enormous quantity of wood was needed to keep the ironworks operating. Timber was cut by nearby farmers working in off seasons and by indentured Scots. 2 The logs were then converted into charcoal by slow burning in sod-covered kilns. The ‘colliers’ who performed this skilled operation were paid high wages. 3 From nearby low-lying marshes and old stream beds, workers dug up a bog iron ore. This was loaded into ox carts for transportation to the Hammersmith furnace. 4 To charge the furnace, ironworkers dumped the mixture of bog ore, charcoal and fluxing material, principally a rock ore mined at Nahant, into the furnace top.

Early visitors to the Iron Works were told in the 1953 guidebook that ‘A number of Scots were brought over to provide a larger crude working force… the value of their services to their employers seems to have been far less than the cost of their maintenance. Few indeed really learned the iron-making trade’.

The first major interpretation of the Scots came in 1958 when Warner S. McCall, a descendent of James Mackall, financed a cast iron plaque to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the arrival of the Scots. In part it reads that they ‘quickly assimilated into the Puritan Community to which they had come as tragic victims of war and in which they remained to aid in the building of a new country and to raise up a large and worthy progeny’. It highlights five men who learned skilled trades, and ‘In doing so they were the forerunners of that mighty army of immigrants to the New World who successfully made the transition from a mainly rural way of life to the crafts and skills on which the growth of our modern industrial America has largely hinged’.

In 1968 Saugus Iron Works was handed over to the US National Park Service. For a historic site to become part of the US national park system, its story must have national significance. The USNPS identified new interpretive themes for the site in the 1970 Interpretive Prospectus, including:

‘The Hammersmith Ironworks is often thought to be the forerunner of American ‘big business’ because of its technological integration of furnace, forge, and slitting mill, operating with assembly-line precision. However, Hammersmith’s real value lay in the catalytic role it played in Puritan New England, its function as a training school for men who went on to other places and built up a fair share of the Colonial American iron industry… Hammersmith was in many respects a ‘first American company town…’.

The 1984 Historical Studies Plan adds: ‘…the Scottish Prisoners of War… faced difficulties in their relationships with the local Puritan community. Their conflicts and eventual amalgamation into the community constitute the iron works’ unique social contribution to the development of the Seventeenth-Century Colony’.

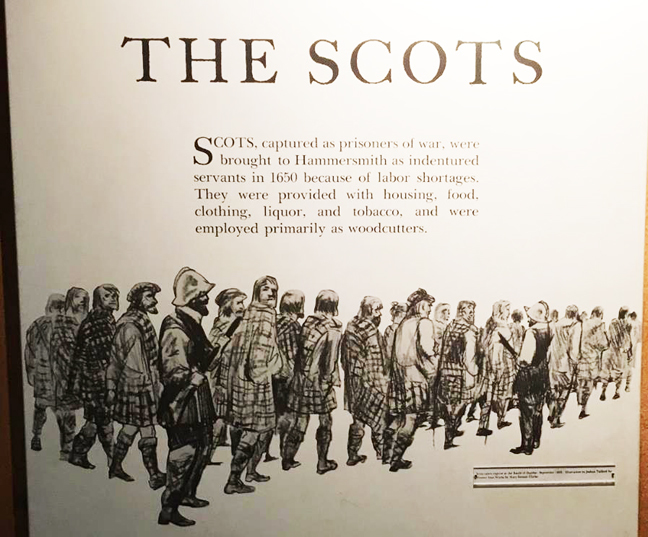

The 1970 interpretive themes were used when the exhibits in the site’s museum building were installed in 1981. The focus of the museum exhibits is on technology and the owners of the iron works, but the Scots Plaque is mounted in the museum next to this panel:

Detail of the panel from the Scots exhibit. Image courtesy of US National Park Service. The text reads: ‘The Scots. Scots, captured as prisoners of war, were brought to Hammersmith as indentured servants in 1650 because of labor shortages. They were provided with housing, food, clothing, liquor, and tobacco, and were employed primarily as woodcutters.

Detail of the panel from the Scots exhibit. Image courtesy of US National Park Service. The text reads: ‘The Scots. Scots, captured as prisoners of war, were brought to Hammersmith as indentured servants in 1650 because of labor shortages. They were provided with housing, food, clothing, liquor, and tobacco, and were employed primarily as woodcutters.

In 2000, new primary and secondary themes of interpretation were completed, and used as the basis for a new general management plan and interpretive programs.

Primary themes:

- Saugus’ 17th century Iron Works helped lay the foundations of America’s modern industry by transferring and dispersing iron-making technology and skilled workers from the Old World to the New.

- Saugus Iron Works was an early example of the New England economic self-reliance that later challenged the emerging British imperial system.

Secondary themes:

- In contrast with our stereotypes of Puritan Society, at Saugus the iron works brought together a diversity of ethnicities, religions, and social values, which we think of as characteristic of America.

- Saugus Iron Works is one of the earliest industrial activities to have an environmental impact on the American landscape.

The USNPS is now beginning the multi-year process of re-examining the interpretation of the site with the eventual goal of installing new exhibits in the museum. Native Americans, women, and other iron workers beyond the wealthy English owners need to be better represented in the museum. The research done for the Durham project offers several exciting new avenues of interpretation for the Scots experience at Saugus Iron Works.

Share this

Archaeology and the Battle of Dunbar 1650: From the Scottish Battlefield to the New World

Archaeology and the Battle of Dunbar 1650: From the Scottish Battlefield to the New World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free