Black Tudors: War, Privateering and Piracy

Share this step

Records show that Africans living in Tudor England also arrived by a third route from the Spanish colonies in modern day Central America, South America and the Caribbean, or from Portuguese or Spanish ships captured by the English at sea.

Conflict in the Caribbean and Spanish Americas

The background to these migrations often lay in Tudor challenges to Spain in the Americas in the period.

Spain had been an ally to England against France in the past, a relationship sealed by marriage: Katherine of Aragon’s to Prince Arthur and then his brother Henry VIII; and later her daughter Mary I’s marriage to Philip II of Spain. But during the reign of the Elizabeth I, Protestant England increasingly saw Catholic Spain as an enemy, and began to fear a Spanish invasion.

England was also jealous of Spain’s great wealth, much of which came from her American colonies, and after 1580, when Philip II also became ruler of Portugal, global Empire.

The English began to try to challenge Spanish power, attacking Spanish shipping and ports, and even attempting to establish their own unsuccessful colony, Roanoke in modern-day North Carolina.

Tensions ebbed and flowed in the first few decades of Elizabeth’s reign, but outright war broke out between the two countries in 1585. Despite the English defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, hostilities continued until 1604, when James I made peace soon after succeeding Elizabeth I to the throne.

Besides the better-known clashes in Europe, Tudor aggression towards Spain included competition for trade routes, rivalry in exploration and circumnavigation, and challenges to Spain as a colonial power.

Privateering and Piracy

Tudor privateering activity against Spanish ships was one route in which Africans came to England from the mid 16th century onwards.

What was privateering and how did it differ from piracy? How did Africans come to Tudor England through privateering activities, naval warfare and piracy against Spain and what were their experiences like?

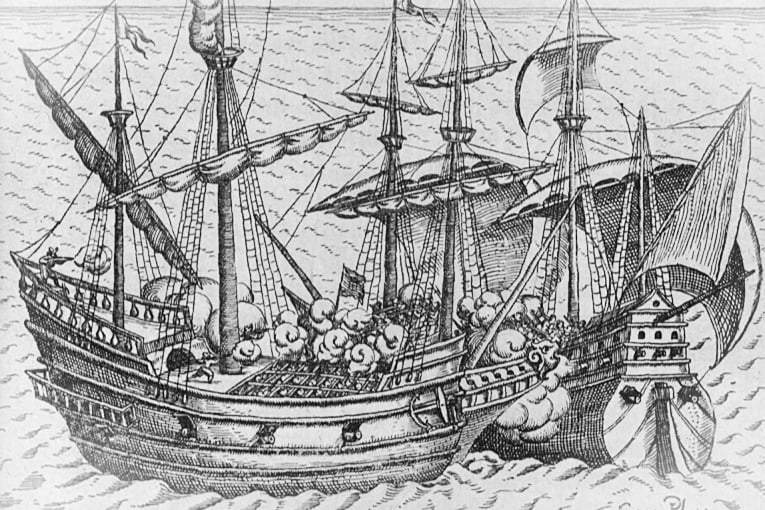

The career of Francis Drake, who became both celebrated and notorious for his successes in privateering offers an example. Tudor privateering involved attacks on foreign ships and the seizing of goods and valuables.

Privateering was a form of legal mercenary activity at sea, practiced by all European maritime nations. It was most common at times of war but could also be approved by the crown at other times.

When a merchant ship was robbed at sea by a foreign ship, the captain could receive royal approval for the seizing of enemy goods equal in value to those he had lost. These approvals were known as letters of marque or letters of reprisal.

Privateering was essentially piracy with royal approval and could form a lucrative sideline for merchants. Some men almost exclusively focused their activities on privateering, which could be much more profitable (though also much more risky) than peaceful trading. Outside war time or without royal approval, activities similar to privateering became piracy and were illegal.

There was a fine line however between approved privateering and piracy, and similarly to the story of John Anthony the Mariner, some 16th and early 17th century English pirates could carry letters of marque from other European rulers.

There was a fine line between approved privateering and piracy, and as in the story of John Anthony, mariner of Dover, some English pirates could carry letters of marque from other European rulers.

Drake’s raids on port towns and land trade routes went beyond typical privateering and were seen by the Spanish, who considered him a dangerous pirate, as acts of war.

Privateering and Encounters with Africans in the Spanish Colonies

Given the trafficking of enslaved people from Africa across the Atlantic to the Spanish colonies, Spanish and Portuguese ships attacked by English privateers frequently had Africans on board. In most cases these were enslaved Africans, but they could also be Africans working in a variety of roles on the ship. Raids on Spanish New World ports also led to the capture of Africans.

In this way privateering activities offered many opportunities for encounters between Africans and English merchants, traders and captains.

Enslavement in the Spanish Colonies in the Americas

What were the experiences of Africans such as Diego who lived in the Spanish Colonies in the Americas?

Records indicate the first enslaved Africans arrived in Hispaniola, now modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic, in 1502 within a decade of the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus.

Enslaved Africans provided a reliable labour force in the Spanish colonies. It’s estimated that 370,000 Africans were trafficked from Africa across the Atlantic to the Spanish Americas in the period up to 1619, often on Portuguese ships.

Initially the Spanish had enslaved the indigenous Amerindian people as a colonial workforce. After many of the Amerindian people succumbed to European diseases, influential writers such as historian and missionary Bartolomé de Las Casas questioned their oppression. New laws were passed in the 1540s protecting Amerindians.

To maintain the lucrative silver, gold and copper mines, and sugar crops, a shift occurred to the enslavement of Africans.

Were some Africans Free in the Spanish American Colonies?

From the first arrival of Africans in the Americas in the first years of the 16th century, across all the European colonies, some enslaved Africans, who became known as Cimarrons by the Spanish (and later Maroons by the British), succeeded in escaping to the mountains or other hinterlands to form free communities, in some areas intermarrying with the native inhabitants. So in the time of Drake and Diego, there were a small minority of free Africans living in the Spanish American colonies.

Find Out More

To visually explore the Spanish colonial world Drake encountered, take a look at the The Drake Manuscript: Histoire Naturelle des Indes from the Morgan Library.

Reflection

- Was Drake a privateer or a pirate?

- How did privateering activity lead to encounters between Africans and Tudor merchants and sea captains?

References

Claire Jowitt (2010) The Culture of Piracy 1580-1630: English Literature and Seaborne Crime, Ashgate Publishing

Wheat, David (2016) Atlantic Africa and the Spanish Caribbean, 1570–1640 University of North Carolina Press

Thornton, John K. and Linda M. Heywood, eds. (2007) Central Africans, Atlantic Creoles, and the Foundation of the Americas, 1585–1660, Cambridge University Press

John H. Elliott (2006) Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492-1830, Yale University Press

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free