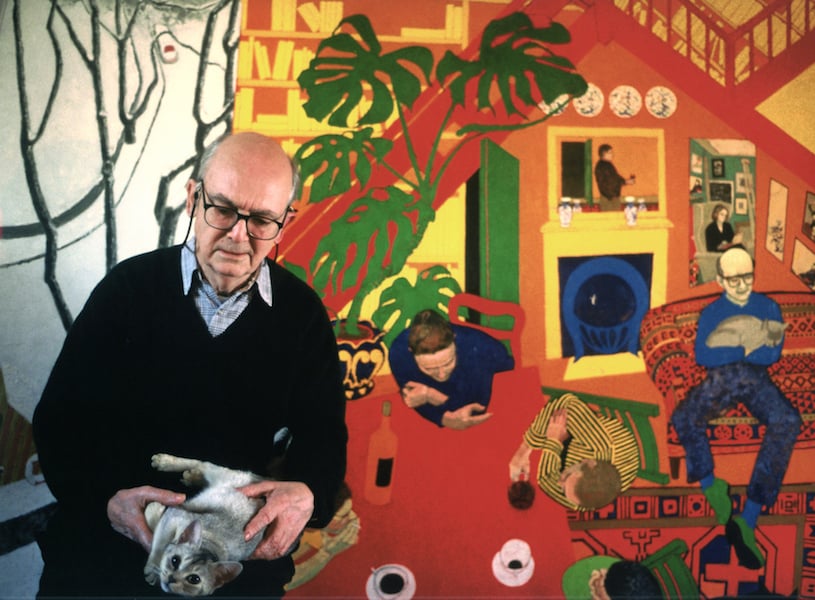

Home / Creative Arts & Media / Dementia / Dementia and the Arts: Sharing Practice, Developing Understanding and Enhancing Lives / William Utermohlen and his self-portraits

This article is from the free online

Dementia and the Arts: Sharing Practice, Developing Understanding and Enhancing Lives

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.