Scottish History: The Protestant Reformation in Perth

Share this step

Protestant ideas came early to the burgh of Perth – understandably, given its important place in the trade networks of the North Sea.

Perth’s mercantile community received new continental ideas right along with merchandise for trade. The town’s craftsmen would have gathered news from abroad as they offered their goods for sale. Indeed, it was the crafts community that seems to have been initially most receptive to the Reformers’ principles. Among Scotland’s earliest protestant martyrs were five Perth craftspeople executed by hanging or drowning on Cardinal Beaton’s order in 1544. Two were maltmen, one was a flesher and another a skinner, and the fifth, Helen Stark, was the wife of the skinner and daughter of a skinner burgess. The charges against them included interrupting a friar in the pulpit to dispute his misunderstanding of the Scriptures, eating a goose on All Hallow’s eve (a fast day), and in Stark’s case, declining to call upon the Virgin during childbirth. What is telling about the event of their execution is the report that ‘there was great intercession made by the town to the governour for their lives’ and that they ‘were carried [to the gallows] by a great band of armed men, for they feared rebellion in the town’. Clearly the authorities perceived a dangerous level of popular support for protestantism already in the 1540s.

Native anticlericalism had fuelled Reformation fires: Sir David Lyndsay’s vigorous critique of monastic corruption, Ane Satyre of the Thre Estatis, targeting among others Perth’s own Carthusian house, had been performed in Perth’s Bow Butts before James V in 1540. It played to a receptive audience: in 1537 two Perth men had been prosecuted for hanging an image of St Francis with a ram’s horns and a cow’s rump attached to it, presumably reflecting resentment of the Greyfriars for the sort of corruption criticised by Lyndsay. In the year before the martyrs were executed, a mob attacked the Blackfriars’ house and paraded their cooking pot through the streets – surely an outcry against mendicant wealth and self-indulgence. At around the same time two burgesses were heavily fined for reading the vernacular Bible and disputing traditional versions of its meaning, and a converted priest (and the town clerk) Sir Henry Elder was banished. Beaton may have thought that his reprisal against the protestant townspeople would stem this tide, but events proved him very wrong: in 1545 the burgh council elected an outspoken protestant, the Master of Ruthven, to serve as provost, rejecting Beaton’s own candidate.

Anticlericalism continued to flourish in the 1550s, along with increasingly vocal criticism of popish ‘superstitions’. Oliver Tullidelph reported that reforming ideas had permeated the grammar school, where early in 1559 a group of craftsmen’s sons, tutored by their fathers in Lyndsay’s criticisms, reportedly hissed and threw their stools at a friar who was trying to teach them about miracles performed by saints and their relics, and in the process criticising protestant preachers. The schoolmaster, Andro Simson, reportedly dechned to punish the boys after they had persuaded him also to read Lyndsay; instead, he told the town council that if the friars ‘would leave off their inveighing against the new preachers, the bairns would be quiet enough’. In March of that year the vigorously anti-monastic ‘Beggars Summons’ was posted on friary doors in the burgh, demanding reform or eviction of the regular clergy on ‘Flitting Friday’, 12 May, the traditional day for tenants to remove at the end of their leaseholds.

Thus when John Knox arrived in Perth to preach on the eleventh of May, tensions were already high. His fiery sermon in St John’s Kirk struck a radical chord with his congregation, and when a priest tried to say mass at its conclusion, a riot erupted that shocked even the preacher. The crowd destroyed the altars and images in the kirk, and proceeded into the town to attack the chapels and beyond its walls to launch a devastating two-day assault on the Charterhouse. Wanton destruction of images in other religious houses followed, together with some demolition of the buildings themselves, though Henry Adamson’s early seventeenth-century claim that they all ‘cast to ground were in one day’ was clearly inflated. Many of their buildings were of stone and lead-roofed, and were best left either for re-use as hospitals (as in the chapels of St Ann and St Paul) or for gradual robbing for home repairs and new construction. Archaeological finds of cut and decorated stones in excavated early modern houses are doubtless the result. Still, Adamson s observation of ‘our blak friers church and place, white friers, and gray/ Prophan’d’ when ‘our Knox did sound,/ Pull down their idols, throw them to the ground’ gives an impression borne out by contemporaries. There was indeed, as he claimed, ‘no credit more to black, white, nor gray gown’. At least fifty monks, friars, chaplains and their servants fled to the regent in Stirling after the attack; others remained to be pensioned off after the official Reformation, or to convert to protestantism and serve the new church.

Some contemporary accounts note the presence of craftsmen in the mob, and it is clear that the town magistrates as well as local protestant lords (including Patrick, third Lord Ruthven and William’s father) were in the congregation and made no apparent effort to curb the crowd’s zeal. That the burgh was protestant before the nation was seems beyond dispute. Certainly the Lords of the Congregation had no difficulty expelling the regent’s troops from the town in June, pronouncing true religion established there.

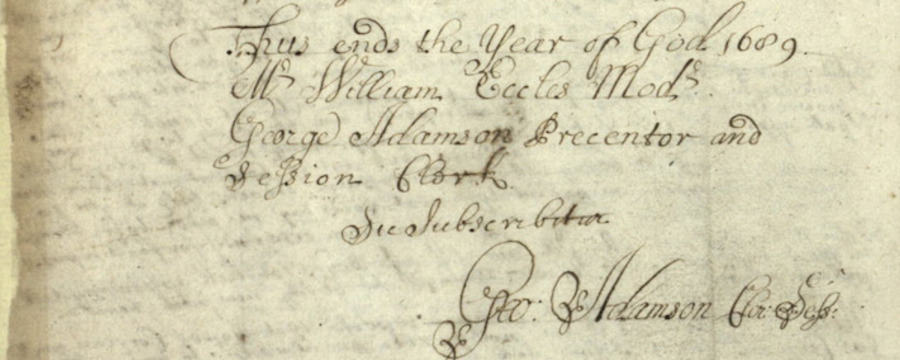

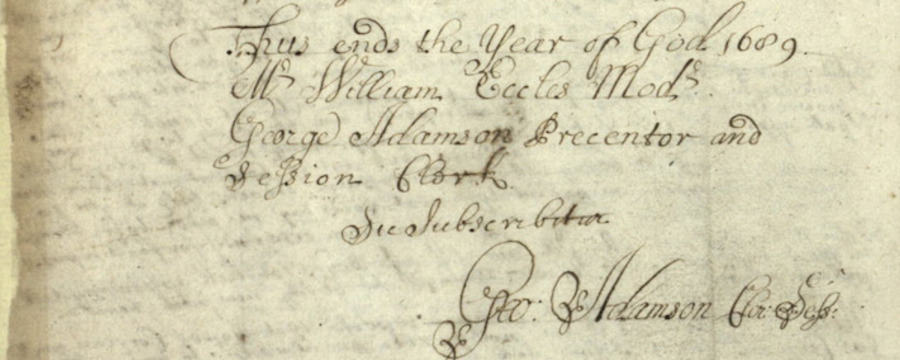

Perth’s elders thus claimed with some reason in the session minutes of 20 November 1587 that theirs was the congregation ‘where the truth first began in this kingdom to be published’. Having arguably begun the urban Reformation, Perth’s leaders proceeded to cement the burgh’s reputation by seeking out a charismatic protestant preacher and pursuing zealously the strict moral discipline prescribed by their Genevan model, finally exceeding even that ‘most perfect school of Christ’ in the rigour of their enforcement. But what they achieved should not be seen exclusively in terms of social control, a phrase that suggests imposition of a programme on a resistant populace. The session repressed sinful behaviour regarded by ‘the elders as also by the voice of the common people to be slanderous to the kirk of this Reformed burgh.’ This was no idle boast. In fact, the success of their endeavours to curb the ungodly in their midst was predicated on broad community approval and active cooperation.

Extract taken from Margo Todd (ed), The Perth Kirk Session Records, Sixth Series, Vol. 2 (Scottish History Society, 2012), pp. 19-23.

Share this

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Early Modern Scottish Palaeography: Reading Scotland's Records

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free