Proposition 3: Personal Net Zero

Share this step

Striving to achieve personal net zero or increased self-sufficiency is the third consideration in this series as a value proposition for adopting V2G. The idea is to maximise the carbon benefits that can be achieved from having on-site renewable installations, such as solar PV. V2G supports this by allowing local solar energy to charge EV batteries during generation peaks. This clean electricity can be used for both: (a) powering the vehicle for transport and (b) discharging to meet other building loads when solar generation dips. As a result, one may reduce their dependency on “dirtier” grid electricity.

As we see continents, countries and local councils making net zero pledges to avert the worst impacts of climate change, some people may be attracted to the idea of bringing this target down to an individual, family or business level.

Consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the climate emergency unfolding around them and armed with this knowledge, look at areas in their own life where their environmental impact can be lessened.

As such, certain lifestyle choices may be made based on reducing one’s carbon footprint through diet, home energy efficiency measures, heating, travel modes, food waste and shopping habits.

Switching to a BEV is another example of an environmentally conscious choice, with separate lifecycle analysis studies undertaken by Ricardo and Transport & Environment demonstrating that BEVs driven in Europe in 2020 had associated lifecycle CO2e emissions considerably lower than those of ICE vehicles. The extent of this varied by country; those with the lowest grid carbon intensity saw the greatest savings. Across the board, this is anticipated to improve with time as national energy supplies are decarbonised in accordance with climate targets.

In addition to these environmental lifestyle choices, increased self-sufficiency may appeal to those who already take measures to gain greater independence and personal sustainability by, for example, growing their own produce in an allotment; or developing skills to repair clothing, electronics, and furniture to avoid buying new. These points can be extended to lowering the environmental impact of energy usage. Installation of renewable capacity, most likely in the form of solar PV but also small-scale wind turbines, provides an avenue to cover household electricity loads, including EV charging, using locally generated clean electricity.

Making use of any locally generated renewable energy supports decarbonisation of local energy consumption by reducing reliance on grid electricity which may be considerably “dirtier” depending on the generation mix at any given time. Although the UK grid has seen significant reductions in the annual average carbon intensity in recent years, reducing 66% between 2013 and 2020, it still has associated environmental impacts with significant seasonal variation. This local energy use also results in cheaper household energy bills since any energy generated by their own renewable assets is free.

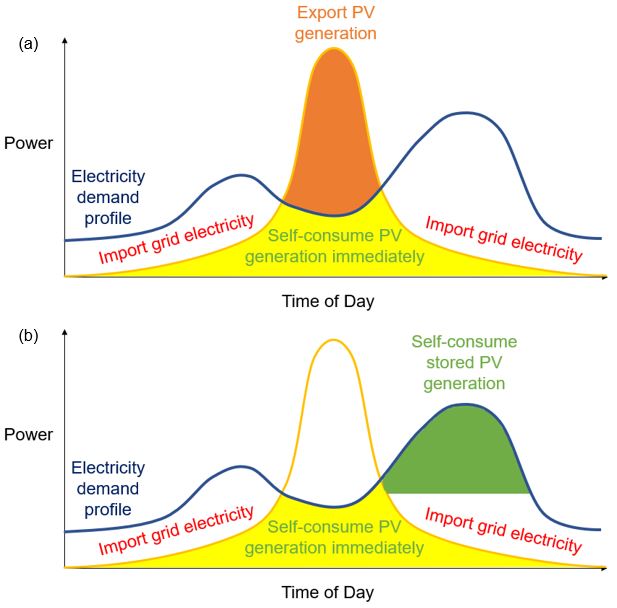

Having the ability to store any excess local renewable electricity, to be consumed by the household later, is therefore advantageous. The domestic stationary battery storage market has developed for this purpose. Figure 1 illustrates how storage devices enable excess PV generation to be self-consumed at peak times rather than merely exported at time of generation.

Figure 1: Household electricity profile with PV installed: (a) without battery storage; and (b) with battery storage

Figure 1: Household electricity profile with PV installed: (a) without battery storage; and (b) with battery storage

V2G, or more accurately V2H or V2B, unlocks much of this benefit to EV owners without needing to invest in a separate storage asset. This requires a level of control via planned scheduling to ensure that the EV battery is left at a suitable state of charge in time for anticipated journeys.

The proposition has a local focus, intending to minimise energy imports with the ambition of relying entirely on generation and storage capacity on-site. Priority is given to consuming energy generated before exporting.

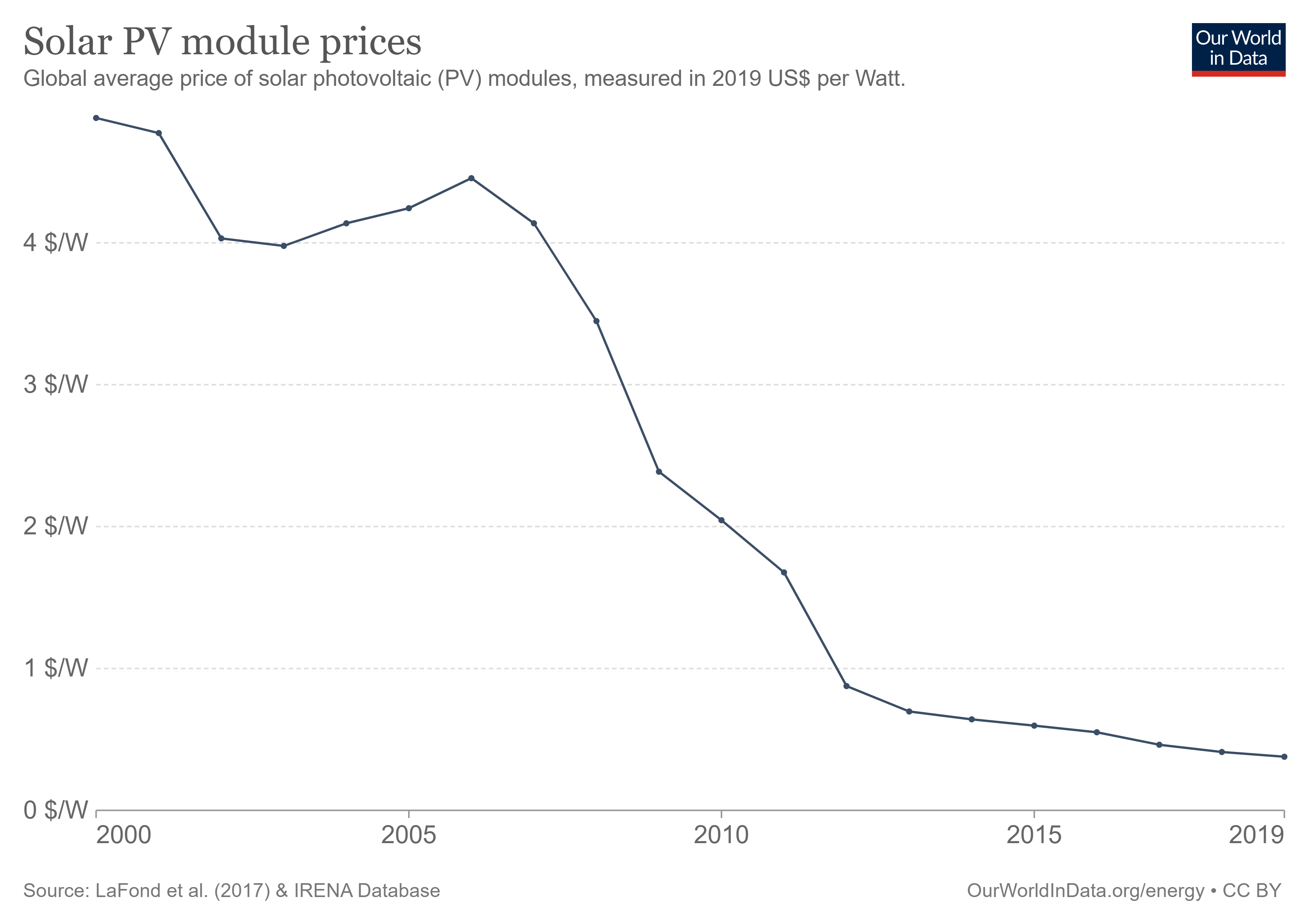

Prices of solar PV panels have been on a significant downward trend over the last 15 years, as can be seen in Figure 2, and as a result, it has never been more affordable to install solar at home than now.

Figure 2: Solar PV module prices

Figure 2: Solar PV module prices

Within the UK, the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) scheme rewarded both generation and export from microgeneration including PV. Applications to this scheme ended in 2019, and it has been replaced by the Smart Export Guarantee (SEG), which provides revenue for export but not generation.

With the a reduction in the value of direct financial reward for newly-registered PV installs, using V2H to support electrical self-sufficiency and self-consumption of PV energy, may be an effective strategy to receive a return on investment. From a domestic perspective, customers may be enticed by the idea of “driving on sunshine” if they can sync their EV charging with periods of high PV generation. Increased homeworking since the COVID-19 pandemic boosts this possibility, with EVs being around for battery top-ups in the brightest hours. This trend also supports V2H operation with clean energy.

There may also be psychological motivations within this value proposition. Competitive neighbours among community groups may wish to claim bragging rights over whose V2H system has been best optimised to demonstrate that they have the highest levels of energy self-sufficiency.

For commercial entities, V2B operation to support the decarbonisation of energy consumption may help them to hit environmental targets and attract eco-minded consumers.

To extract maximum value, EVs parked on the premises would need sufficient available storage capacity to match generation on any given day, and then be available to discharge back into the premises to offset import. An example could be a vehicle fleet which has early morning operations, returning to site to charge from solar power generated in the early afternoon and then discharging during the evening or overnight when site demand exceeds generation. Of course, the vehicles would need to retain sufficient state of charge for the next day’s operations.

Key Takeaways

In summary, striving for personal net zero could be an effective incentive to adopt V2G for individuals who feel empowered to lead by example in response to the climate emergency. There are few technical and legislative risks, the narrative of increased self-consumption is easy to understand for the end user and there is increasingly strong consumer interest in the importance of being environmentally friendly. Its success relies on the customer’s ease of integrating on-site generation, demand and storage in such a way that carbon emissions are minimised, whilst not restricting their use of the vehicle for driving needs.

What Do You Think?

Can you think of people in your life who would be motivated by this proposition? If so, what traits do they have in common?

Do you think it is better to try to consume all your renewable generation on-site, or let the surplus spill on to the electricity network? What impacts might lots of customers exporting have on the low-voltage network?

Add your thoughts into the discussion below.

Share this

Vehicle-to-Grid Charging for Electric Cars

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free