Designing for Disabilities: Evidence Based Interventions

Improved access to public services can empower persons with disabilities and improve quality of life (1, 2). Persons with disabilities face barriers to accessing services, including stigma, limited rehabilitation providers, lack of trained health professionals, inaccessible transport and infrastructure (1). Exploring how the limited number of existing interventions, aiming to address these barriers are designed, is useful for developing future interventions.

This article gives an overview of two such interventions: a Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) intervention for people with intellectual impairments and their carers in Nepal and a stroke rehabilitation programme in India (3). These interventions used a systematic approach recommended by the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Framework (4) and the Behaviour-Centred Design (BCD) model (5). These approaches have similar steps and common processes for intervention development.

The process of designing evidence-based interventions

The MRC framework and the BCD model steps to design an intervention are:

Step 1: Identify the desired outcome. Review literature for existing evidence on the topic, issue or behaviour of interest, any interventions that exist to improve the situation (see step 1.18 for information on evidence synthesis). Do primary research with the target population to understand their requirements, behaviours, and barriers to accessing the service.

Step 2: Identify how to bring about change based on theory and evidence. Identify key stakeholders and hold a participatory workshop with them to a) discuss and validate preliminary research findings b) develop a theory on how the intervention is expected to influence change c) develop the intervention.

Step 3: Pilot test the intervention to understand its feasibility, acceptability, and options for implementation.

Step 4: Deliver the intervention at a wider scale, and conduct a process and impact evaluation.

What this looks like in practice

The Bishesta campaign: a menstrual hygiene intervention for people with intellectual impairments and their carers in Nepal.

Identify the desired outcome

A systematic review was conducted to explore the menstrual hygiene requirements of people with disabilities and their carers, the barriers to MHM, and evidence on existing interventions (6). Findings showed: inaccessible water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities for managing menstruation; people with intellectual impairments missed out on MHM information, and pre-menstrual symptoms were poorly understood and managed. Carers struggled when people with intellectual impairments did not follow socio-cultural norms (e.g. showed their menstrual blood to others); there were no support mechanisms for carers so they felt isolated and overwhelmed (7). Consequently, the intervention outcome identified was: ‘improved MHM practices and dignity for people with intellectual impairments’.

Identify how to bring about change based on theory and evidence

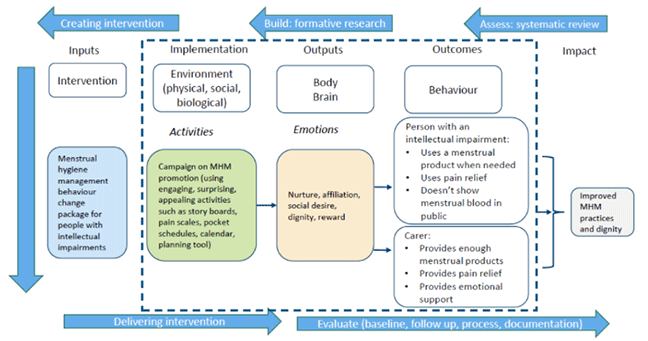

Preliminary research findings were validated by carers, policy makers, and implementers. Findings from the systematic review and preliminary research led to the development of a Theory of Change (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Theory of Change for the Bishesta campaign

A creative team was formed to develop the intervention: to encourage people to adopt the target behaviours, two fictitious characters were created who already carry out the behaviours – Bishesta (left) and Perana (right) – Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bishesta and Perana

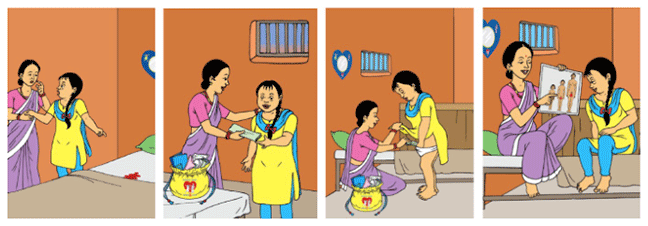

Period Packs for people with intellectual impairments were designed to encourage them to adopt the target behaviours (Figure 3). Carers were given a calendar to help track the person’s menstrual cycle (8).

Figure 3 Period pack contents

Left to right: menstrual storage bag with products; menstrual shoulder bag for use outside the home; a menstrual bin.

Visual story of Bishesta menstruating for the first time and Perana supporting her through the process.

Pilot test the intervention

The intervention was piloted with ten people with an intellectual impairment and their carers through group training sessions. All participants were regularly visited by facilitators to provide support and monitor the adoption of target behaviours. Feasibility and acceptability of the intervention was assessed through a structured questionnaire before and after the intervention, and by gathering process monitoring data to understand if the campaign was delivered as intended. Findings showed that the Bishesta campaign was acceptable, largely delivered as planned, participants used most of the period pack contents, and there were improvements across all the target behaviours (9).

Care for Stroke; A smartphone-enabled, Carer-supported educational intervention for management of physical disabilities at home

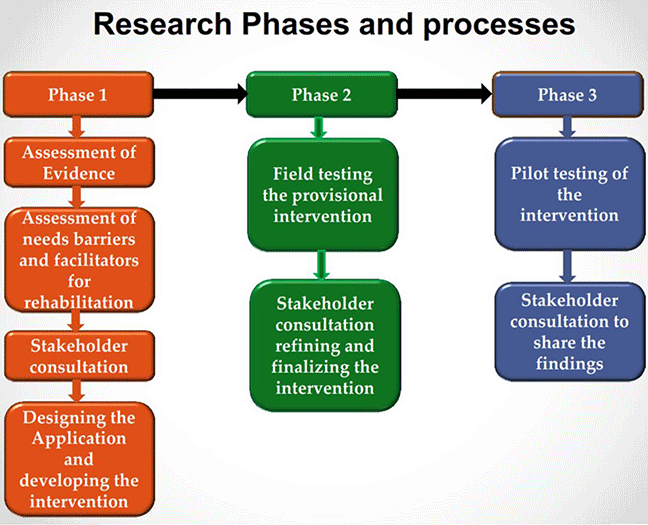

It is not easy or practical to directly adapt evidence-based interventions for post-stroke rehabilitation from high resourced settings to low resourced settings such as India (10). Therefore, a rehabilitation intervention that is sensitive to the needs, culture, and context of stroke survivors in India was systematically developed, following the process set out in Figure 4 (11).

Figure 4. Process of developing a stroke rehabilitation intervention in India

Identify the desired outcome

Systematic reviews were conducted on the epidemiology of stroke in India, the effectiveness of educational interventions for stroke survivors to understand the stroke burden, and the evidence on existing interventions (12, 13). Preliminary research was also carried out to understand the needs of stroke survivors, carers, and stroke rehabilitation professionals, to gain in-depth insights about the barriers and facilitators of developing the intervention (14, 15).

Identify how to bring about change based on theory and evidence

Evidence from the systematic reviews and preliminary research was shared with a group of stakeholders including stroke survivors, carers, and stroke rehabilitation and technology experts. Stakeholders discussed and advised on the content of the intervention, which was developed based on their recommendations.

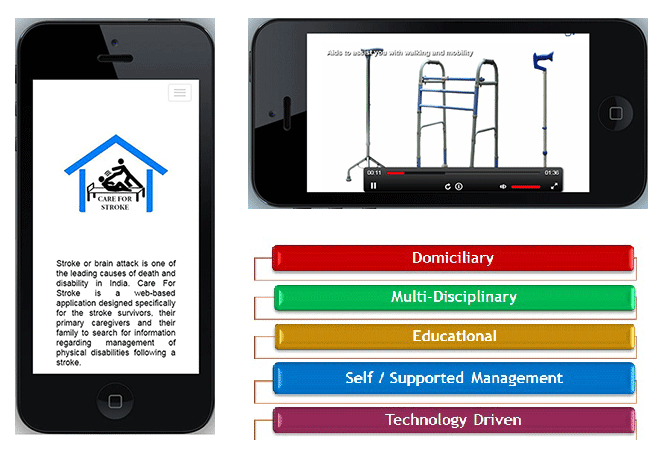

The ‘Care for Stroke’ intervention is web-based and smartphone-enabled. Content is educational and focuses on the management of physical disabilities following stroke in the home of the affected individual. The intervention is in digitised audio-visual format that can be used by stroke survivors, with or without support from their carer at home. The key advantages of the intervention are shown in Figure 5 (3).

Pilot test the intervention

Piloting was carried out in two stages. First stage: the intervention was provided to a set of stroke survivors to assess the operational issues. Several issues such as poor video-streaming, internet-connectivity and picture quality were identified. The intervention was completely revised as recommended by the stakeholder team. Stage two: the refined and finalised intervention was tested with another group of stroke survivors to understand its feasibility and acceptability (16).

Figure 5. Advantages of the Care for Stroke Intervention

Deliver the intervention at a wider scale

The intervention is currently being evaluated for its effectiveness through a trial in India (17). If found effective, the intervention will be strategically scaled up throughout the country and its impact will be assessed.

Question to consider:

- How could you apply this structured approach to intervention design in your setting?

- Who would you engage through the process to ensure the intervention is sustainable and scaled up?

Share this

Global Disability: Research and Evidence

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free