Social contract and political pact

Share this step

If social order stems from a divine decree or simply from nature, then human beings cannot be placed at its centre, and change does not make sense: how could humans possibly go against such forces?

Following this vision, societies are simply fundamentally unfair. Yet, this injustice is sometimes accepted as either being desired by God and therefore transitory since one hopes to find a better position in the afterlife; or as being an intrinsic, almost unavoidable part of life.

If, on the contrary, the idea of social justice triumphs, then society must be organized according to principles that benefit everyone and this balance must be guaranteed by a “social contract”.

Similarly, the opposition must be respected and treated fairly, for it could be the next in power: a “political pact” is required, to guarantee fair policy-making.

These two models (natural order and desired order) clash in the world. The former could come out winning, since those who support it are often inclined to proselytism, which does not fail to upset the others.

Social contract or natural law?

The social contract, to begin with, is set up between rulers and the governed in order to avoid being subject to natural laws.

With La Fontaine’s, The wolf and the lamb, or The lion and the fox in Kalila-wa-Dimna, the Arab-Persian count who served as La Fontaine’s inspiration, the message is clear: injustice is a natural fact; the weak must therefore be cunning when dealing with the powerful.

Left: The Wolf and the Lamb, by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, public domain. Right: A page from Kelileh o Demneh, depicts the jackal trying to persuade his lion-king that the honest bull-courtier, is a traitor, public domain.

Contrary to the message conveyed by these narratives, the social contract clearly divides natural order and political order.

The Englishman Francis Bacon distinguishes social laws from the laws of nature, his motto is: “nam et ipsa scientia potestas est”: science is power, at the very origins of the idea of progress desired by man.

The Frenchman René Descartes (1596-1650) opposes reason to providential order; “cogito ergo sum”: I think therefore I exist. This motto is at the roots of rationalistic individualism.

Rousseau is one of the inventors of the social contract, which was the title of his 1762 book. He is certainly not the first to have imagined it, though he is the one who most clearly expressed the idea. Yet, this contract is not a European invention, as people sometimes believe.

The quest for a just order is indeed ancient and universal. For the Pharaohs or Mesopotamian sovereigns, in ancient China or Japan, it dominated political thought for centuries.

And there is famous testimony: the code of Hammurabi. This king who ruled over Babylon 38 centuries ago recorded the law code on a famous stone stele, a replica of which can be seen in many museums and law schools in the world.

The Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian law code of ancient Mesopotamia, dating back to about 1754 BC. It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world. Public domain.

This pioneer made the text public for present and future generations:

That the strong might not injure the weak, in order to protect the widows and orphans … in order to bespeak justice in the land, to settle all disputes, and heal all injuries, (I have) set up these my precious words, written upon my memorial stone, before the image of me, as king of righteousness.

These ancient philosophies contrast with ours as they have a different way of tackling the question: should we seek a more just order, or content ourselves with living in a less unjust society?

This is the bottom line of the controversy between the American John Rawls and the Indian Amartya Sen.

The former focuses on principles of justice everyone can agree on, on a social order a priori, decided in an abstract manner by people with no experience of life in society who would not be aware of their actual position once the social order is constituted.

Rawls believed that these “constituents” would build a liveable society even if they found themselves in a disadvantaged position when this imaginary society became reality.

Sen, on the other hand, states that we are unable to say what is intrinsically right, in absolute terms, though we are perfectly capable of identifying injustice when we see it (exploited children, for example).

These two thinkers’ opposing ideas reflect the confrontation of two philosophies: one, procedural, the other substantial.

Today, the procedural conception has triumphed (with formal guarantees that protect individuals). Yet, humanity has principally been marked by the substantial conception (with tangible benefits distributed according to people’s needs).

Equality and equity

Other differences also matter, such as the distinction between equality and equity.

Whereas egalitarian justice erases all hierarchy (it redistributes income through progressive taxation), justice as equity guarantees everyone’s fair place in a social order in which merit is rewarded (you get your fair share according to your effort and ability).

The justice as equity conception therefore accepts differences in income and rewards, because they are justified by differing levels of talent.

However, this all requires somebody saying what is fair and what is not, and obviously it mustn’t be someone who might benefit from that decision, as we see in this cartoon.

By Nina Paley, used under CC licence.

A large part of the world now lives in an equity-based regime (for example, the Indian world). Another part remains strictly hierarchical in practice (for example, the Chinese, Muslim – despite a true ideal of equality – and Russian worlds).

Equality is above all a European concept: the idea of a social contract guaranteeing justice for all is not particularly commonplace.

The political pact

And what about another form of social contract, not between the elite and the population, but within the elite themselves: the “political pact”?

This term refers to behaviour: the way the political elite (including the opposition which is a prospective majority) refrains from condemning others to prison, exile, torture or house arrest, to avoid becoming victims of it when no longer in power.

A more demanding variant of this is a pact allowing parties in power to benefit from immunity for even illegal or inhumane acts once they are no longer in power (outgoing governments) or when they come to power (today’s leaders were yesterday’s illegal opponents).

Here are four examples.

In Argentina

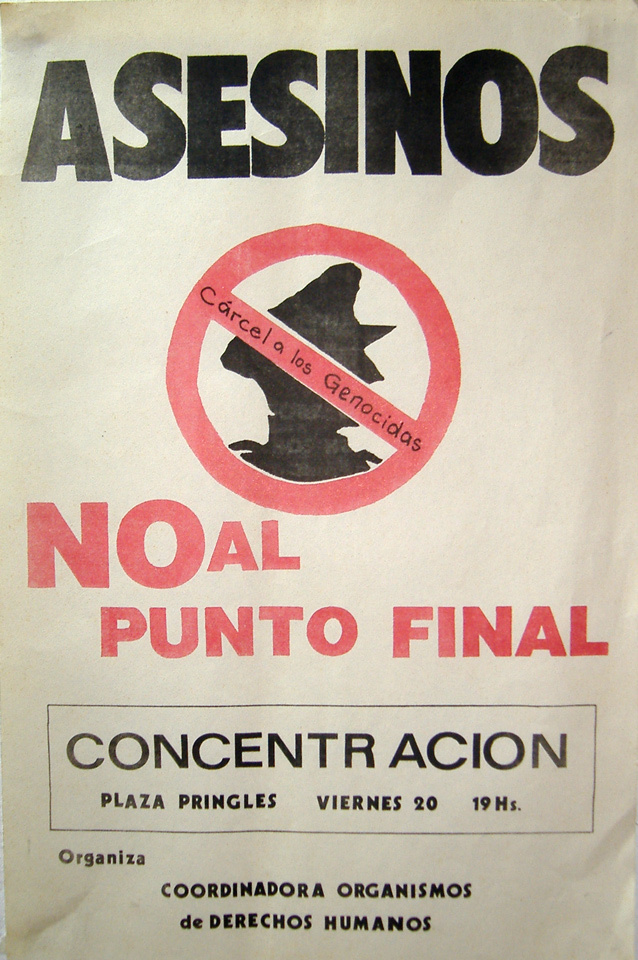

The first example of a political pact is Argentina in 1986: the newly elected radical president elected by universal suffrage, Raul Alfonsin, enacted a law, against the wishes of his supporters, banning prosecution for crimes committed during the dictatorship.

An announcement of a demonstration against the Ley de Punto Final (Full Stop Law), passed in Argentina after the last military dictatorship in order to stop the multiple crime investigations against military, police and others.

By Pablo D. Flores, used under CC licence.

This is why it was called the “full stop law” (Punto Final), once and for all.

In Chile

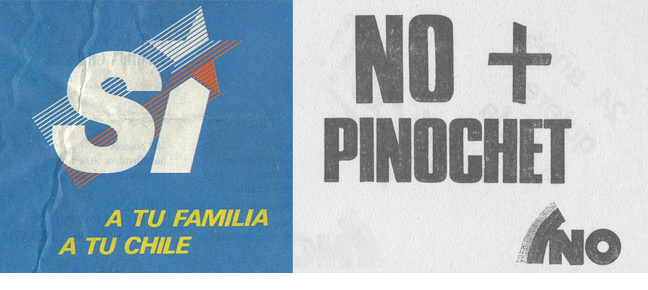

The second example is the political pact in Chile (here we see the ballots used for the constitutional referendum after which Pinochet stepped down of his own free will).

By Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional, used under CC licence.

In the USSR

The third, less successful example was the political pact in the USSR: Perestroika triggered the end of the Soviet Union, but it did not force the still mighty security services from power.

In South Africa

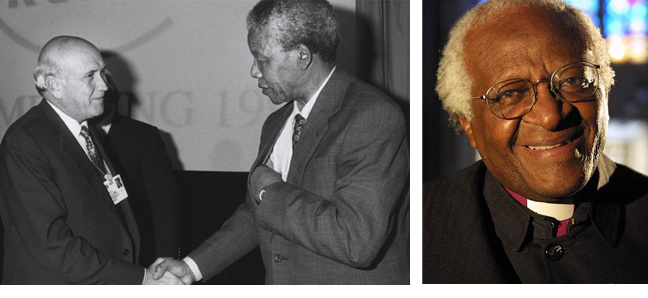

The fourth example was a successful pact: in South Africa, when the new constitution ended apartheid for good, the pact led not only to a change of rulers, but to true reconciliation.

In this picture, former President De Klerk and former prisoner Mandela seal their agreement to start afresh; on the other, the South African bishop Desmond Tutu is the one who invented the concept of reconciliation between victims and persecutors.

Left: Frederik de Klerk and Nelson Mandela shake hands at the Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum held in Davos in January 1992, © World Economic Forum,used under CC licence. Right: Archbishop Desmond Tutu, public domain.

Repairing the social fabric requires shared determination. The principle is simple: “a fault confessed is half redressed”: the persecutors confess their crimes, and the victims forgive them.

Conclusion

Two major conceptions of the world have clashed since the beginning of history; each has a certain conception of justice.

Before acting, either rulers set up a social contract with the governed, and a political pact with their opponents; or the notion of justice is considered natural, in which case the natural or providential order cannot be undermined.

However, even heavenly or natural justice can be slightly modified: for example, one can avoid injustice to others whenever one sees it; or, political opponents can be guaranteed immunity for their action and ideas, even before they need it.

Societies based on opposing organizational principles can thus come closer together, despite their contradictory points of view, instead of confronting each other in an alleged ‘clash of civilizations’.

Share this

Global Studies: Cultures and Organizations in International Relations

Global Studies: Cultures and Organizations in International Relations

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free