The Ethics of Water

Share this step

What do ethics have to do with water and water security? Ethical dimensions take on an increasing significance as human interventions, both intended and unintended, increasingly impact on the water others may need.

Ethics relate to how decisions are made and choices taken, rather than presenting a normative position on the status of water itself. It also raises important cultural questions of how water is perceived.

Consideration of the ethical dimension to water security is a relatively recent development, although the ethical concepts used have a long history.

In this article, we explore the various ethical aspects of human interventions into water systems. In doing so, we consider cultural, moral and religious attitudes towards water and the implications of this for debates on water security.

How do we value water?

One of the first questions to be considered is what we mean when we refer to water and how we then choose to value it.

Does water have an intrinsic value for example, or should it be regarded simply as an economic good, much like coffee is?

A human right to water

Every person has the right to between 50 and 100 litres of water per day for personal and domestic use, from a source that is within 1,000 metres of their home and does not take more than 30 minutes to collect. The cost of this water should not exceed 3% of household income. (Resolution A/RES/64/292. United Nations General Assembly, July 2010)

Do rivers and ecosystems have rights too?

Human interventions affecting water availability

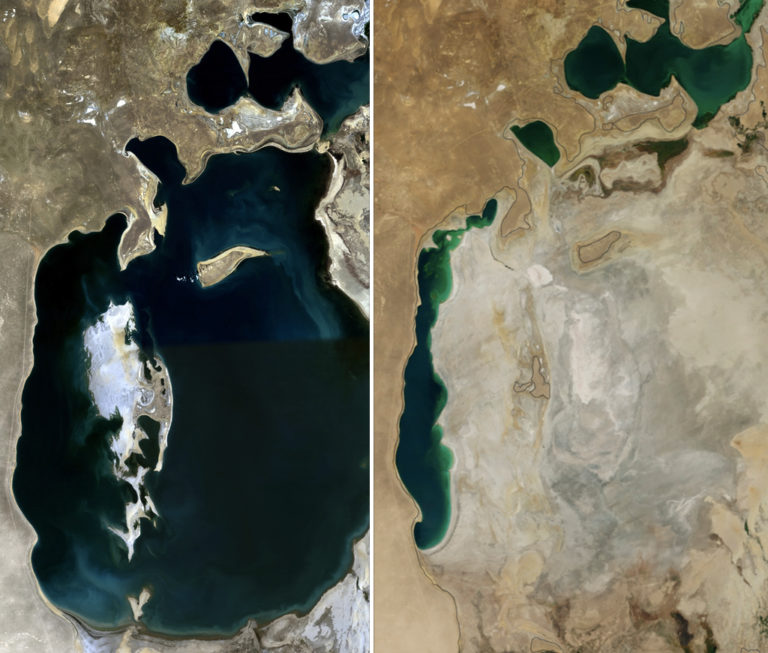

The Aral Sea

A comparison of the Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right). NASA. Collage by Producercunningham, Public domain.

A comparison of the Aral Sea in 1989 (left) and 2014 (right). NASA. Collage by Producercunningham, Public domain.Sea of Galilee

Construction of dams

A thing is right if it preserves or enhances the ability of the water within the ecosystem to sustain life; and wrong if it decreases that ability (Armstrong 2006, p. 13).

However, others argue that it is rare to find examples of an intervention that universally sustains life, most tend to privilege some forms of life over others. This has led authors to suggest that the real question is how humans take responsibility for their interventions.

This raises fundamental questions as to how decisions are made, by whom, and how these managers value different, and often competing, claims on water. At a more philosophical level we are also left to ask whether nature should be valued for its own sake, rather than only in relation to how it meets human needs.

Over to you

- What value do you give to water?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free