Home / Creative Arts & Media / Design / Invitation to Ex-Noguchi Room: Preservation and Utilization of Cultural Properties in Universities / Architecture of the Noguchi Room at Keio University

This article is from the free online

Invitation to Ex-Noguchi Room: Preservation and Utilization of Cultural Properties in Universities

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

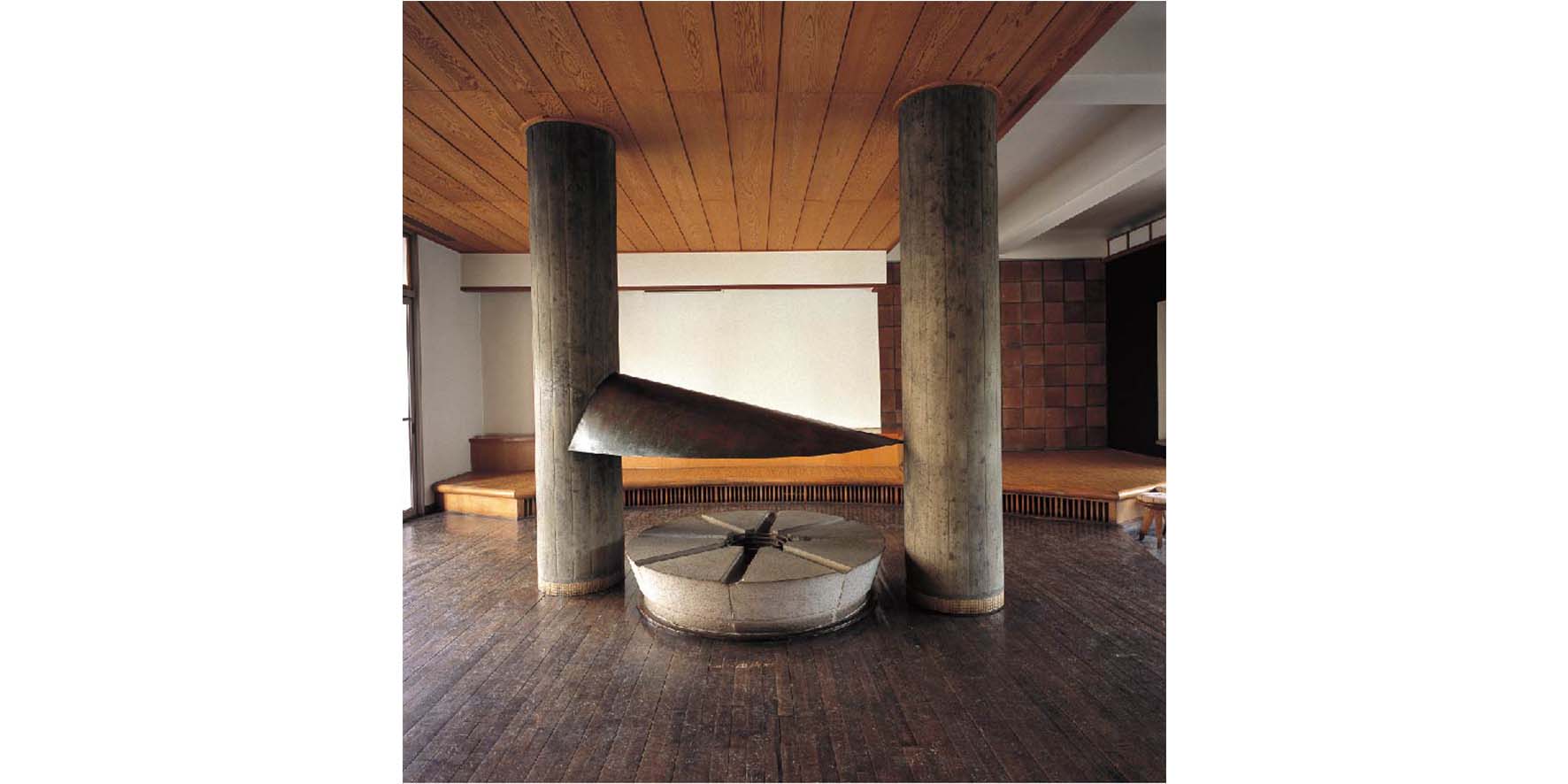

Natural materials like the rattan and rushes of the floor, ceiling panels and furniture, and the stone of the floor, coexist with the concrete of the columns. (©Shigeo Anzaï (Source: Kajima Institute Publishing))

Natural materials like the rattan and rushes of the floor, ceiling panels and furniture, and the stone of the floor, coexist with the concrete of the columns. (©Shigeo Anzaï (Source: Kajima Institute Publishing))

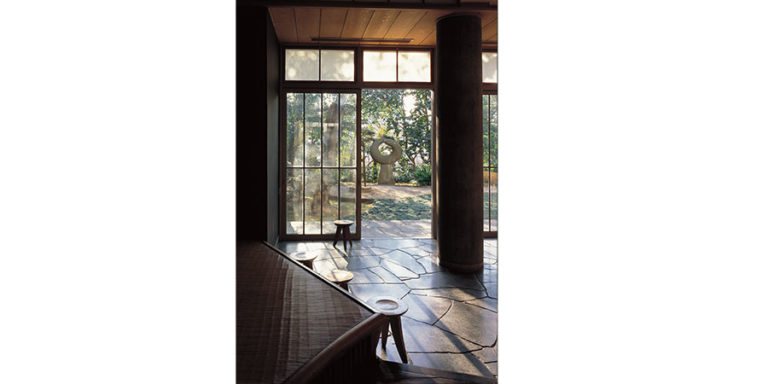

View of garden from second floor of the Second Faculty Building.

View of garden from second floor of the Second Faculty Building.  Garden and Mu seen from inside the Noguchi Room (©Shigeo Anzaï (Source: Kajima Institute Publishing))

Garden and Mu seen from inside the Noguchi Room (©Shigeo Anzaï (Source: Kajima Institute Publishing))