Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) Study: Pros & Cons

Below are extracts of a fictive article from a study that uses a rapid appraisal method called knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study.

KAP studies are frequently used. We invite you to read the abstract and extracts that are shown below and to reflect on the following questions:

- What are the advantages of the study?

- What are the shortcomings of the study and why?

1. (Fictive) AbstractThere are many infectious diseases transmitted from pets to people. These zoonotic diseases are viruses, bacteria, parasites or fungi and also antibiotic resistant bacteria. Allergens are not considered as zoonoses. However, there is little information about the knowledge of pet owners.We wanted to assess the knowledge, attitude and practices of pet owners. For this, we conducted a questionnaire-based study among pet owners in two dog training courses and among cat owners in three veterinary clinics. In total, 56 pet owners agreed to participate (32 dog owners and 24 cat owners) and were interviewed with the structured questionnaire.In addition, we made notes on our observations. A major finding was that a majority of pet owners (80.3%) could list rabies as a zoonosis, but only a few knew at least two zoonoses (17.9%). Most interviewees believed that the risk of zoonoses from pets was small. Many wrongly believed that washing hands regularly was sufficient to prevent diseases that can be potentially acquired from pets.Only a few dog owners reported that they received much information about zoonoses from their veterinarians, whereas this proportion was significantly higher among cat owners (15.5% vs 83.3%). All interviewees wanted more information on zoonoses in pets. Pet owners seemingly use a range of different names for zoonotic diseases when they were probed.We observed that virtually all dog owners collected the faeces of their dogs (96.9%) and, of these, 64.5% washed their hands afterwards (however there was a large difference of this practice between the two training settings).In conclusion, the knowledge on zoonoses among pet owners was poor. Public health education programmes are needed and veterinarians need to better inform dog owners.© Swiss TPH (Esther Schelling)

2. Extracts from (fictive) methods and materialsThe two dog training courses took place during weeks 32 and 33 of the year 2015. They were organized by the same conveners but were in different locations (30 kilometers apart). The three veterinary clinics in the same range were all contacted and agreed to participate. Cat owners were interviewed during the same time period (3 to 14 August 2015).A cross-sectional descriptive study using questionnaires was designed to assess knowledge, attitudes, practices and beliefs of pet owners regarding zoonoses. We presented the study to all dog owners of a training course and enrolled all willing to participate (18 and 14 participants in course A and B, respectively). Interviews were conducted after the course in a nearby restaurant.For cat owners, owners coming to one of the three clinics (16, 2 and 6 in clinics A, B and C, respectively) were asked to participate while the veterinarian was waiting for the next patient. We excluded other pet owners such as owners of guinea pigs or reptiles.The questionnaire included 33 closed questions and 8 open-ended questions. The open-ended questions were on local names used for zoonoses and local practices. We observed and took notes of behaviors of owners. In addition we took photos.3. Extracts from (fictive) results3.1 Knowledge on zoonoses

Different sources of information were reported when probed. Interestingly, cat owners significantly more often reported veterinarians as a source of information than dog owners (15.5% vs 83.3%, chi square p-value <0.001).Knowledge of pet owners in relation to zoonosis (stratified by dog and cat owners)

This table summarises knowledge indicators among dog and cat owners.

3.2 Attitudes

The majority believed that the risk of zoonotic diseases from their pets was minimal (on a scale from 1-5). However, when probed almost all stated that they were afraid of rabies and wanted more information on zoonoses from pets.3.3 Practices

We observed that 31 out of 32 dog owners collected the dog faeces, which is an important public health measure. When we asked cat owners if they immediately collect cat faeces, none reported to do so, but at least 12% and 33% said that they clean the cat litter every 24 and 48 hours, respectively. Regarding other important hygienic measures, we observed that a total of 64.5% of dog owners washed their hands after collecting faeces with a plastic bag – a good personal hygienic measure.However, we found differences in this good practice: of the participants enrolled who collected faeces, a total of 88.2% (15 out of 17) in course A washed their hands, but only 35.7% (5 out of 14) did so in course B. This result was significant (Fisher’s exact p-value of 0.007).In addition, we observed that more women than men washed their hands. We also observed that particularly dog owners were smokers. This can be a predisposing factor to acquire air-borne zoonoses, such as tuberculosis, and should be included in education material.3.4 Beliefs

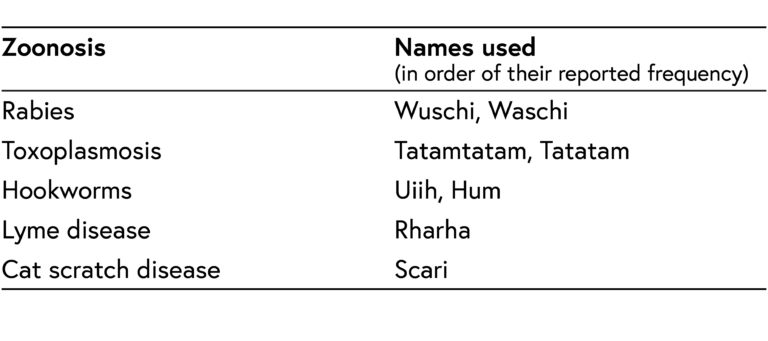

Some interviewees believed that rabies can be cured. However, they also seemed to mistake rabies for another disease. We found that pet owners used different names for the same disease.Names pet owners use for major zoonotic diseases in pets

4. Extracts from (fictive) discussionDespite that the majority of pet owners knew about rabies (and that it is transmitted by animal bites), only 60.7% of the interviewees knew that it was caused by a virus. Therefore, not all knew that it could be prevented by vaccination of dogs and cats. Importantly, we found a belief that rabies can be cured.One limitation of this study may be that we could not further evaluate the relationships between a zoonosis and its reported local names.You might agree that it was good that the authors combined different approaches such as observation and questionnaire interviews to assess the knowledge, attitude and practices.We do not know for how many days data was collected at a course site, but we can assume that the 18 and 14 participants were interviewed within a couple of days since interviewers were present and received the permission of the course conveners to conduct these interviews. The findings are interesting in view of the astonishingly low knowledge on zoonoses. This is in spite of the fact that the authors have gathered names used by pet-owners for the zoonoses. However, we do not really know if these were assessed prior to the interviews and then used in the questioning.Alternatively the researchers might have assessed these local names in parallel with knowledge of, for example, toxoplasmosis and only then were the participants asked how they called the disease causing this and that symptom. The study led to a rather straightforward recommendation to increase education among pet owners. However, we do not learn much about which particular aspects of knowledge should be addressed and what are the best entry points for effective information on risk and prevention because the understanding of issues at hand remains very superficial.During interviews, people tend to give answers that they believe to be correct from the perspective of the interviewer or of other listeners if interviews are not conducted privately. In the case of interviews at veterinary clinics, it would be inappropriate if, for example, the consulted veterinarian were present. When knowledge of interviewees is not in good agreement with the biomedical model, it is often labeled as ‘beliefs’ since more information on the socio-cultural constructions is not available and alternative interpretations can be found. Local knowledge could represent good entry points for information campaigns or to strengthen resilience of communities.

Now, think about what you have just read. What do you like and where do you identify shortcomings?

Share this

One Health: Connecting Humans, Animals and the Environment

One Health: Connecting Humans, Animals and the Environment

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free