Women and Nature: The Countesse of Montgomery’s Urania

Share this step

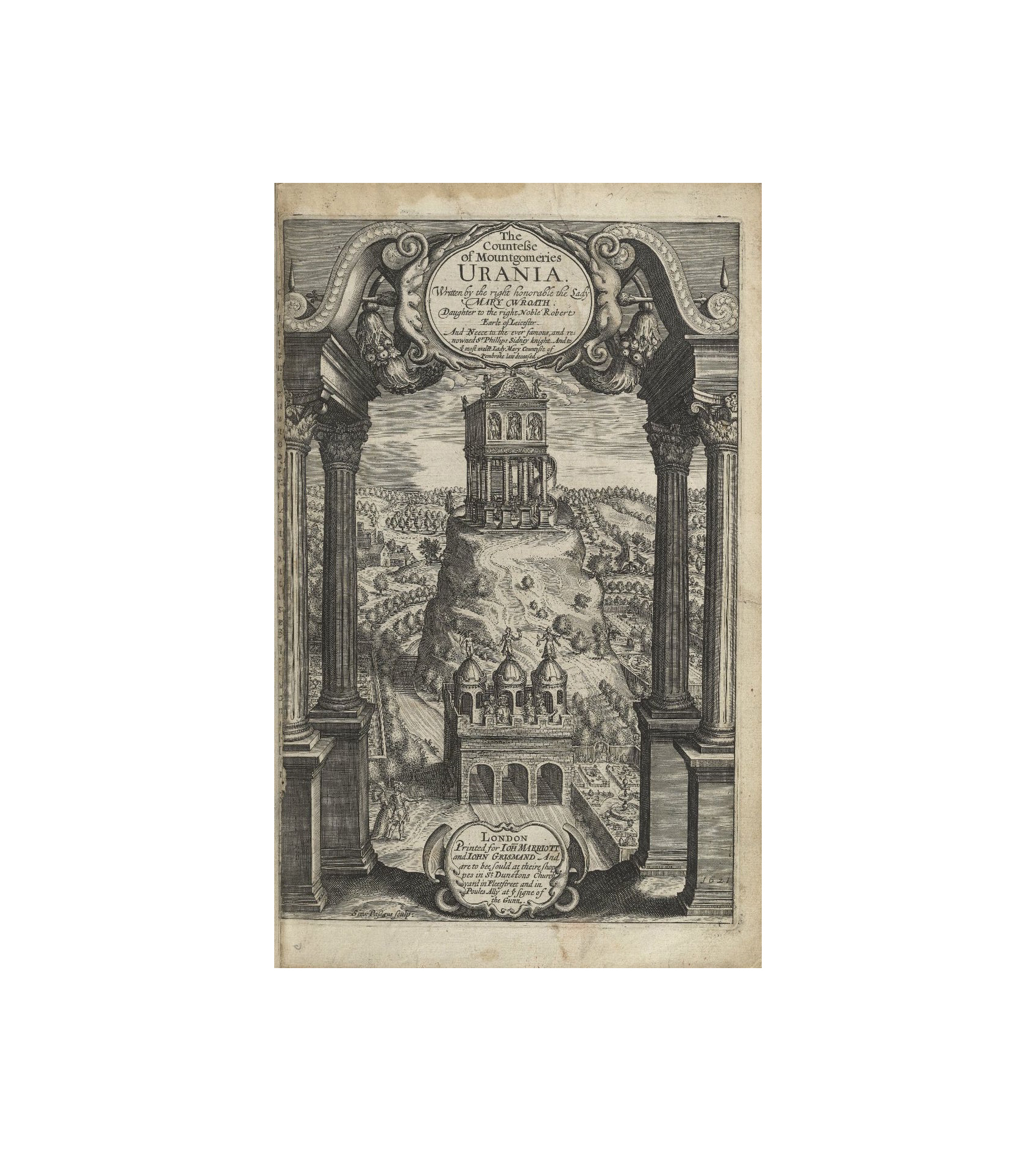

How does the landscape of pastoral change in the hand of a female Sidney writer? In this article we will read the beginning “The Countess of Montgomery’s Urania” (1621), written by Lady Mary Wroth, Sir Philip Sidney’s niece.

These are the opening pages of Lady Mary Wroth’s story which introduce the title character, Urania, who has been living as a shepherdess but now knows that she is the daughter of the King and Queen of Naples.

Consider the following questions to guide your reading.

- How does the mood of this extract contrast with that in the extracts from Sir Philip Sidney’s “Arcadia”?

- What kind of pastoral landscape is depicted in this extract and how is it linked to Urania’s feelings?

- How are poetry and writing intertwined with the landscape in this extract?

When the Spring began to appear like the welcome messenger of Summer, one sweet (and in that more sweet) morning, after Aurora (1) had called all careful eyes to attend the day, forth came the fair Shepherdess Urania, (fair indeed; yet that far too mean a title for her, who for beauty deserved the highest style could be given by best knowing Judgements). Into the Mead(2) she came, where usually she drove her flocks to feed, whose leaping and wantonness showed they were proud of such a Guide: But she, whose sad thoughts led her to another manner of spending her time, made her soon leave them, and follow her late-begun custom; which was (while they delighted themselves) to sit under some shade, bewailing her misfortune; while they fed, to feed upon her own sorrow and tears, which at this time she began again to summon, sitting down under the shade of a well-spread Beech; the ground (then blest) and the tree with full, and fine leaved branches, growing proud to bear, and shadow such perfections. But she regarding nothing, in comparison of her woe, thus proceeded in her grief: “Alas Urania,” said she, “(the true servant to misfortune); of any misery that can befall woman, is not this the most and greatest which thou art fallen into? Can there be any near the unhappiness of being ignorant, and that in the highest kind, not being certain of mine own estate or birth? Why was I not still continued in the belief I was, as I appear, a Shepherdess and Daughter to a Shepherd? My ambition then went no higher than this estate, now flies it to a knowledge; then was I contented, now perplexed. O ignorance, can thy dullness yet procure so sharp a pain? and that such a thought as makes me now aspire unto knowledge? How did I joy in this poor life being quiet? blest in the love of those I took for parents, but now by them I know the contrary, and by that knowledge, not to know my self. Miserable Urania, worse art thou now then these thy Lambs; for they know their dams, while thou dost live unknown of any.”By this were others come into that Mead with their flocks: but she esteeming her sorrowing thoughts her best, and choicest company, left that place, taking a little path which brought her to the further side of the plain, to the foot of the rocks, speaking as she went these lines, her eyes fixed upon the ground, her very soul turned into mourning.“Unseen, unknown, I here alone complain To Rocks, to Hills, to Meadows, and to Springs, Which can no help return to ease my pain, But back my sorrows the sad Echo brings. Thus still increasing are my woes to me, Doubly resounded by that monefull voice, Which seems to second me in miserie,

And answer gives like friend of mine own choice. Thus only she doth my companion prove, The others silently do offer ease;

But those that grieve, a grieving note do love, Pleasures to dying eyes bring but disease. And such am I, who daily ending live,

Wailing a state which can no comfort give.”In this passion she went on, till she came to the foot of a great rock, she thinking of nothing less than ease, sought how she might ascend it; hoping there to pass away her time more peaceably with loneliness, though not to find least respite from her sorrow, which so dearly she did value, as by no means she would impart it to any. The way was hard, though by some windings making the ascent pleasing. Having attained the top, she saw under some hollow trees the entry into the rock. She, fearing nothing but the continuance of her ignorance, went in, where she found a pretty room, as if that stony place had yet in pity, given leave for such perfections to come into the heart as chiefest, and most beloved place, because most loving.The place was not unlike the ancient (or the descriptions of ancient) Hermitages, instead of hangings, covered and lined with Ivy… This richness in Natures plenty made her stay to behold it, and almost grudge the pleasant fullness of content that place might have, if sensible, while she must know to taste of torments. As she was thus in passion mixed with pain, throwing her eyes as wildly, as timorous Lovers do, for fear of discovery, she perceived a little Light, and such a one, as a chink doth oft discover to our sights. She curious to see what this was, with her delicate hands put the natural ornament aside (3), discerning a little door, which she putting from her(4), passed through it into another room, like the first in all proportion, but in the midst there was a square stone, like to a pretty table, and on it a wax-candle burning; and by that a paper, which had suffered itself patiently to receive the discovering of so much of it as presented this Sonnet (as it seemed newly written) to her sight:Here all alone in silence might I mourn, But how can silence be where sorrows flow? Sighs with complaints have poorer pains out-worn, But broken hearts can only true grief show.Drops of my dearest blood shall let Loue know Such tears for her I shed, yet still do burn, As no spring can quench least part of my woe, Till this live earth, again to earth do turn.Hatefull all thought of comfort is to me, Despised day, let me still night possess; Let me all torments feel in their excess, And but this light allow my state to see.Which still doth waste, and wasting as this light, Are my sad days unto eternal night.“Alas Urania” (sighed she)! “How well do these words, this place, and all agree with thy fortune?”

Notes

(1) Aurora] the goddess of the dawn

(2) Mead] meadow.

(3) put the natural ornament aside] pushed aside the curtain of ivy leaves.

(4) putting from her] pushing away from her i.e. to open it.

Share this

Penshurst Place and the Sidney Family of Writers

Penshurst Place and the Sidney Family of Writers

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free