Creoles, Creolisation, and Atlantic Colonial Society

The term ‘creole’ and the process of creolisation have multiple definitions, often dependent on geographical and temporal contexts. In some cases, definition of creole is underpinned by linguistics (i.e, Haitian Creole language). For others, creole refers to a culture and communal identity (i.e., Louisiana Creoles*). As a language, culture, identity, or subsequent process, it is grounded in hybridity: the mixing of two or more things to produce something new.

The origin of the term, creole, is obscure. In regard to Atlantic communities, the process of creolisation began during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Scholars agree that there are several possibilities: Caribbean origin; invented by Spanish conquistadors that is a derivation of the Spanish word ‘crear’ or the Portuguese word ‘criar’: to create; an African (Kikoongo) word that meant ‘outsider’ to Africa and born in the Atlantic world.

At minimum, Europeans, colonists, and enslaved Africans assigned the term, creole, to those born and raised in the Atlantic world by the nature of geography. Since the onset of European contact and throughout the colonial era, Whites remained the racial minority (even if politically powerful) demographic in the Caribbean. As early as the 1630s, the colonial hierarchy was supported by large and disenfranchised Black population, most of them enslaved; above them were the poor-to-working class of Whites of small tract farmers, some skilled labourers but most usually occupied menial jobs associated with the plantation economy. At the top of the colonial hierarchy were the few but wealthy slaveholders merchants, plantation owners, and colonial administrators.

Furthermore, for a variety of reasons, the White population did not grow naturally; and due to a high mortality rate, White creoles, regardless of class or economic distinctions, began to decline during the 18th century. As such, White colonial culture, had to adapt to a radically different climate, environment, food practices, etc. away from the norms of British culture. White men also took sexual advantage of enslaved women that led to the creation of racially mixed communities, many of which were allotted a free status.

1750 Demographics in Barbados and Jamaica 1

Barbados

| White | Slave | Free persons of colour | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16,772 | 63,410 | 235 | 80,417 |

Jamaica

| White | Slave | Free persons of colour | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,000 | 127,881 | 2,119 | 142,000 |

Therefore, a creole could be White or Black.

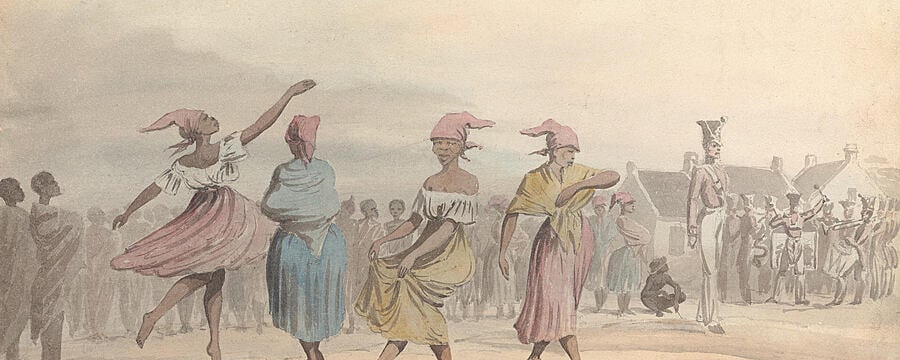

‘Linen Market, Dominica’ painting by Agustino Brunias, ca. 1780 Public domain

‘Linen Market, Dominica’ painting by Agustino Brunias, ca. 1780 Public domain

For colonials born and raised in the islands, trips to the mother country brought to light glaring differences in accent and mannerisms that required a degree of cultural adjustment while residing in the UK. For non-colonials, whether residing the islands or observing colonists back in Britain visiting their ancestral homes, they made numerous pejorative comments, suggesting that creole Whites were culturally inferior to their British-born counterparts.

It is extraordinary to witness the immediate effect that the climate and habit of living in this country have upon the minds and manners of Europeans … they have become indolent and inactive, regardless of everything but eating, drinking and indulging themselves, and are almost entirely under the domination of their mulatto favourites. In the lower orders they are the same, with the addition of conceit and tyranny.2

The subtext of creole is one that is not ‘pure’, not only because of locale but because of creolisation- the process of cultural and/or racial mixing. In relation to enslaved Blacks, there was also the distinction between ‘salt-water negroes’-those born and raised in Africa and enslaved Creoles*. The children of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean embodied the process of creolisation, incorporating cultural aspects (i.e., linguistics, foodways, religions, etc.) from Britain, West African heritages, and in some cases, indigenous Caribbean, resulting in a new and hybrid culture.

Creolisation and creole as a process, identity, language or cultural system, have confusing and complication definitions with multiple perspectives because temporal, geographical, communal, and individual factors that can sometimes contradict each other. As a process, creolisation is continuous play of rejection, adaptation, and accommodation. But when necessary or desired, it was also one of imitation and invention.

In its simplest definition, it is a mixing. But more importantly, it is the movement away from the original (be it European imperialist viewpoints or African cultural authenticities. Today, the majority of Caribbean peoples identify as Black (with a very small local white minority) who proudly claim a Creole identity. But it is important to remember that the historical process was the site social tensions and conflict, born out of violence and forced to conform to a colonial racial and cultural hierarchy that situated whiteness and British language and culture at the top and blackness with African cultural aesthetics at the bottom.

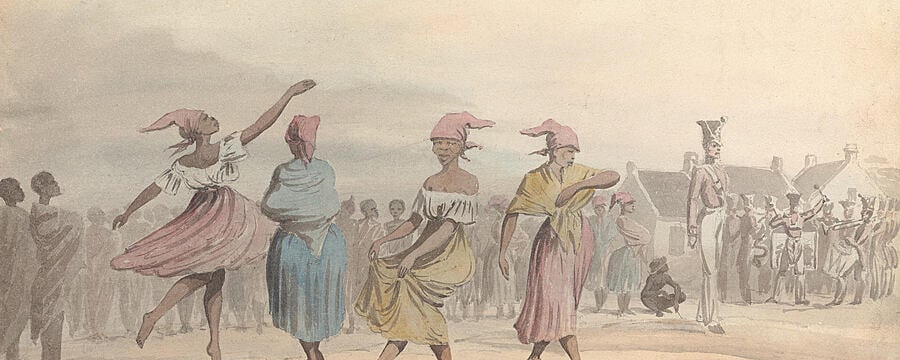

Consider the pastel painting, The Creole Women (Les femmes créoles), by Joseph Savart, 1770.

The Creole Women (Les femmes créoles), by Joseph Savart, 1770. Public domain

The Creole Women (Les femmes créoles), by Joseph Savart, 1770. Public domain

These four Creole women, mostly likely culturally similar yet with differing skin tones, demonstrated the plurality of a colonial Caribbean creole society. The focus of the painting is on the lightest women whose gazes meet the viewer. However, the darker toned women admiringly look to their lighter complexed counterparts. Furthermore, the woman with the darkest skin holds a plate of food to denote her status as a servant or perhaps an enslaved.

*When creole is capitalised, it is to reference a cultural identity or language voluntarily embodied by the individual/community rather than designated by an outsider.

1Engerman, Stanley L., and Barry W. Higman. “The demographic structure of the Caribbean slave societies in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.” In General History of the Caribbean, pp. 45-104. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2003.

2Philip Wright (ed.), Lady Nugent’s Journal of her Residence in Jamaica, 1801- 1805 (Kingston: Institute of Jamaica, [1907] 1998.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free