Clothing for the Enslaved

In eighteenth and nineteenth-century Britain clothing was an essential marker of social status.

With the expansion of the British empire these western notions of dress were transferred to the Caribbean, along with the idea that this same clothing could mark the perceived racial inferiority of enslaved people. Clothing was also a powerful tool for expressing belonging and identity, a fact which was quickly recognised by the European enslavers. The relationship between enslaved, enslaver and dress began with the Middle Passage when captive Africans were stripped of their clothes for the crossing. One account by ʿAlī Eisami Gazirmabe, also known as William Harding, recorded by the linguist Sigismund Koelle many years later recounted,

“The white man took us. We had no shirts. We had no trousers. We were naked. Into the midst of water, into the midst of a ship they put us.”

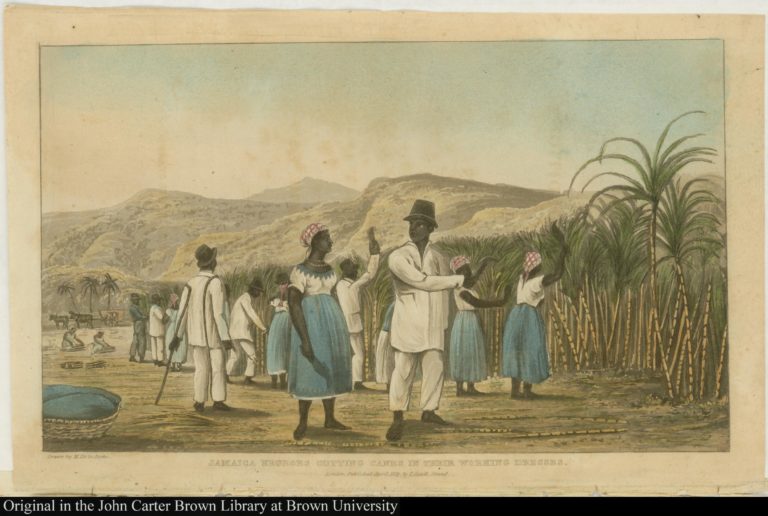

Henry T. De La Beche, ‘Jamaica Negroes Cutting Canes in their Working Dresses’, T. Cadell, Strand, London, 1825. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Henry T. De La Beche, ‘Jamaica Negroes Cutting Canes in their Working Dresses’, T. Cadell, Strand, London, 1825. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. “For clothing, the owner gives to each slave in the year six yards of blue stuff, called bamboo, and six yards of brown. The young people and children are given a less allowance, in proportion to their size and age; the young children getting only a small stripe to tie round the waist. For bed-clothing, they give them only a blanket once in four or five years; and they are obliged to wear this till it falls in pieces. If the slaves require other clothes, they must buy them out of their own little savings. Many of the field negroes are very badly off for clothing.”

Enslaved people who worked as domestic servants rather than amongst the sugar canes held a different status in the racial and social hierarchy. They were expected to dress in a manner which reflected the wealth and status of the household which meant they often had better quality and a greater quantity of clothing than their field-working counterparts. Some enslaved male servants had jackets of broadcloth, fine linen shirts and breeches rather than trousers. In the 1830s, a Scottish woman, Mrs Carmichael, observed that the enslaved female servants of St Vincent wore “fine light calico printed gowns, or white muslin” accessorised with a “a Madras handkerchief about the neck… good necklaces, ear-rings, gold rings, and a nice handkerchief for a turban.” Better clothes did not necessarily mean a better lifestyle, however, and women in particular were subjected to sexual abuse and exploitation.

While clothing was a tool of oppression, it could also be a site of resistance and agency. The colour red, for example, had various meanings amongst different African societies, from representing mourning, warfare or resistance, to invoking protection. Agostino Brunias’s painting The Linen Market, Dominica, c.1780 shows how red might have appeared in the checked and striped cloth worn by enslaved and free women. The painting also shows various headwraps which had prominent links to African style and heritage and were worn by women across the islands. The different styles sent messages about heritage, occupation and on some islands even indicated if a woman was single or married.

Agostino Brunias, Linen Market, Dominica, ca.1780. Yale Center for British Art., https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:586

Agostino Brunias, Linen Market, Dominica, ca.1780. Yale Center for British Art., https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:586

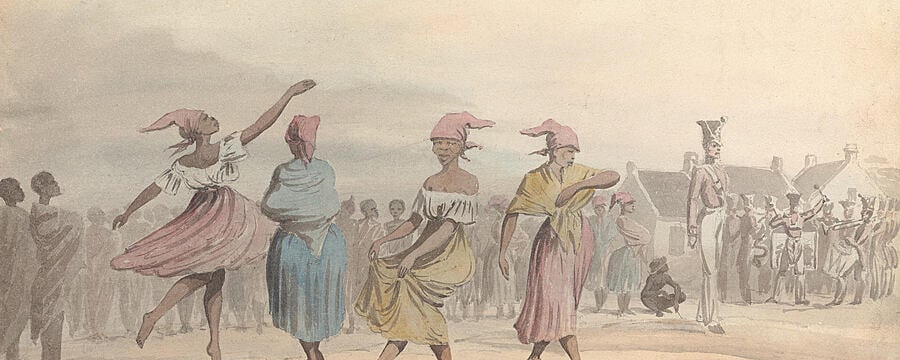

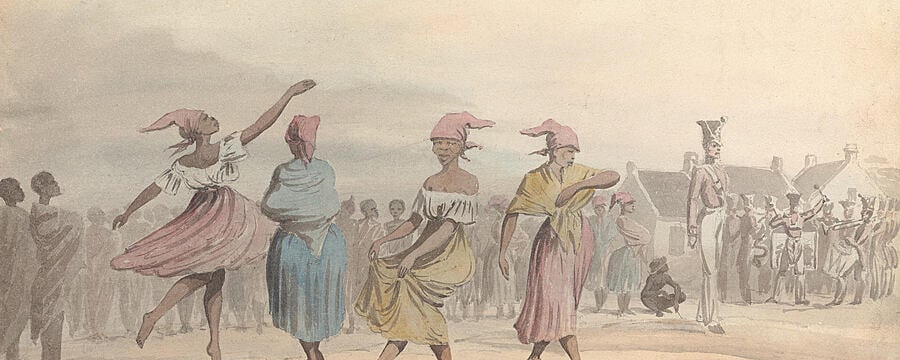

Extra garments could be obtained by selling or bartering vegetables or poultry. Waistcoats, bodices, stockings, or jewellery could become prized possessions worn at special occasions. Christmas, for example, was traditionally when enslaved workers were given two or three days off from their labour and was a prime time for carnivals. Carnivals such as Jonkonnu in Jamaica were creolised celebrations drawing on West African traditions of dance, music, masks and costumes. Staged within the colonial context these events were an opportunity for enslaved people to use dress to create and portray their own communal identity, often subverting European dress codes at the same time. Jaw-bone or House John Canoe, for example, shows the masquerader dressed in striped trousers, often worn by sailors, with the addition of coloured ribbons at the sides. The mask, wig and military-style jacket evokes British imperialism but red also had symbolic meanings for African cultures that could transcend and subvert the British connection. Many aspects of the clothes of the enslaved were controlled but regulating what someone thought or felt when they wore or saw a particular outfit was impossible.

Further Reading

Steeve O. Buckridge, The Language of Dress: Resistance and Accommodation in Jamaica, 1760-1890 (University of West India Press, 2004)

Carol Tulloch, The Birth of Cool: Style Narratives of the African Diaspora (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free