Covert: strikes, religion and belief

In essence, covert resistance is any action that does not seek to overturn the institution of slavery but instead, provides respite or a sense of freedom for the individual or a small group. For many scholars, the definition is flexible enough to include any act of defiance, including the will to survive in the midst of labour practices meant to work a person to death. Malnutrition was an unfortunate and problematic constant on many plantations.

As said in Week 2, obstinate slaveholders consciously ignored their responsibility to labourers, therefore the enslaved had to go hunting and gathering, keep small gardens and even steal food to supplement their meagre provisions. Additionally, colonial law failed to force enslavers to look after the basic needs of the slave community.

Cuffy the negro’s doggrel description of the progress of sugar, E. Wallis, London, 1823. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. This illustration for a children’s book about sugar cultivation and slavery shows a child in the background stealing sugar cane for essential nutrition. Even infringements like this could be severely punished.

Cuffy the negro’s doggrel description of the progress of sugar, E. Wallis, London, 1823. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. This illustration for a children’s book about sugar cultivation and slavery shows a child in the background stealing sugar cane for essential nutrition. Even infringements like this could be severely punished.

Covert resistance, unlike overt resistance (ie., open rebellions, etc), could be performed daily and most certainly occurred before African captives landed on Caribbean island colonies. Historical accounts detail many instances of slave resistance on slaving ships during the Middle Passage. It could take the form of personal protest by self-mutilation, suicide, and infanticide. Other forms of covert resistance included the slowing of plantation work, intentionally breaking farming tools, destruction of plantation crops, poisoning farm animals, working slower, or going on strikes which all negatively affected production. Withholding information on the whereabouts of fugitives or feigning ignorance were also common practices.

Plantation families also worried about poisoning. Some enslaved domestics used their proximity to slaveholders and their families to tamper with their drinks, spirits, and meals. For example, in 1815, a fifteen-year-old enslaved girl named Minetta, was sentenced to death for poisoning her enslaver’s brandy and watching him die. Minetta also allegedly poisoned the coffee which two bookkeepers fatally consumed. Interestingly, a repeating colonial narrative posits poisoning as the strategy of enslaved women but made possible by sorcerous Obeah men.

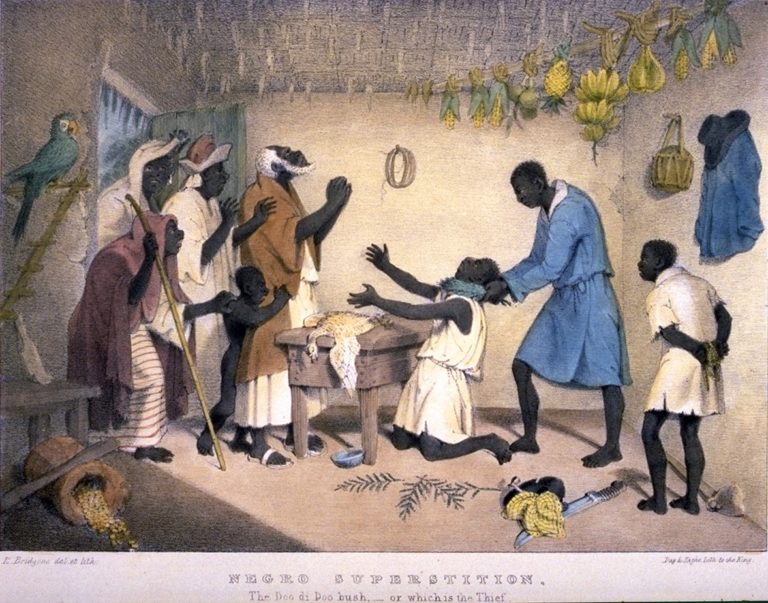

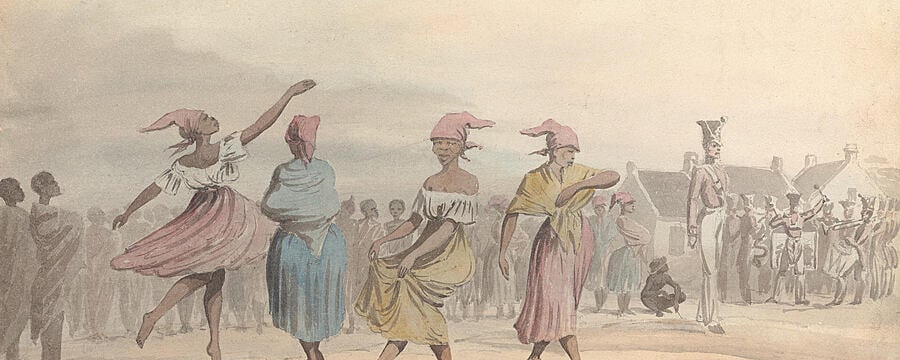

An Obeah Practitioner at Work, Trinidad, 1836 Public Domain. Source: Slaveryimages.org

An Obeah Practitioner at Work, Trinidad, 1836 Public Domain. Source: Slaveryimages.org

Pro-slavery propaganda of the 18th century frequently made the claim that enslaved people were given the opportunity to convert to Christianity. The reality was that many enslaved people already held deeply-felt spiritual beliefs, whether from African indigenous traditions or Islam. Despite the fact that Islam proscribed the enslavement of Muslims, an unknown number of Muslims were trafficked to the British Caribbean through the 18th and 19th centuries. Richard Madden, a magistrate sent to Jamaica by the British government to oversee emancipation, reported that he met several men fluent in Arabic, one of whom had written out the Quran from memory.

Abu Bakr Saddiqi (also known as Edward Doulan) wrote an account of his enslavement, where he described how he “acquired the knowledge of Al Coran in the country of Gounah, in which country there are many teachers for young people.” He was abducted as a youth, stripped, tied and marched through Buntocoo to the town of Cumasy (Kumasi). Despite his trials, he held onto a strong faith:

“We were three months at sea before we arrived in Jamaica, which was the beginning of bondage. But, praise be to God, who has everything in his power to do as he thinks good, and no man can remove whatever burden he chooses to put on us, as He has said, ‘Nothing shall fall on us except what He shall ordain; He is our Lord, and let all that believe in Him put their trust in Him.’”

‘Not long since, some of thee execrable wretches in Jamaica introduced what they called the myal dance, and established a kind of society, into which they invited all they could. The lure hung out was that every Negro initiated into the myal society would be invulnerable to the white men; and, although they might appear slain, the obeah-man could, at his pleasure restore the body to life’. (Edward Long, History of Jamaica 1774, p. 449)

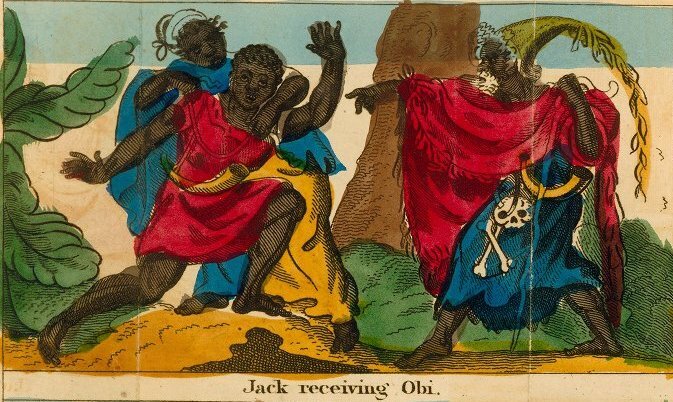

Fairburn’s edition of The wonderful life and adventures of Three fingered Jack, the terror of Jamaica! : Giving an account of his perservering courage and gallant heroism in revenging the cause of his injured parents, J. Fairburn, London, 1825. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

Fairburn’s edition of The wonderful life and adventures of Three fingered Jack, the terror of Jamaica! : Giving an account of his perservering courage and gallant heroism in revenging the cause of his injured parents, J. Fairburn, London, 1825. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

By the mid-eighteenth century, concerns over African spirituality and its potential to stimulate open slave rebellion pushed Jamaica to pass its ‘Act to Remedy the Evils Arising for Irregular Assemblies of Slaves’ in 1760. African or creolised African religious practices intertwined with overt rebellions was a common phenomenon throughout the Caribbean for British, French, Dutch, and Spanish colonies. For example, Haiti’s Maroon leader Makandal (1758) and Cécile Fatima (1791) along with Jamaica’s Nanny (1730s) and Sam Sharpe (1831) were religious leaders that led or influenced slave rebellions. Caribbean laws forbidding Obeah under penalty of death. Even the possession of Obeah materials was worthy of expulsion from the British Caribbean to exile in Cuba. Creolised African religious practices continued to be condemned long after emancipation. The criminalisation of Obeah stayed on the books until the twenty-first century.

Pro-slavery activists in Britain falsely claimed that the system of slavery helped to spread Christianity among the enslaved. In reality, many enslavers opposed the propagation of the Christian faith as they feared it would weaken their control over enslaved people, or give them ideas about freedom. Missionaries were frequently blamed for slave resistance and revolt. An edited version of the Bible was even published in 1807, titled ‘Select parts of the Holy Bible for the use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Islands’.

You can download a pdf version of the so-called ‘Slave Bible’ held at the University of Glasgow Special Collections.

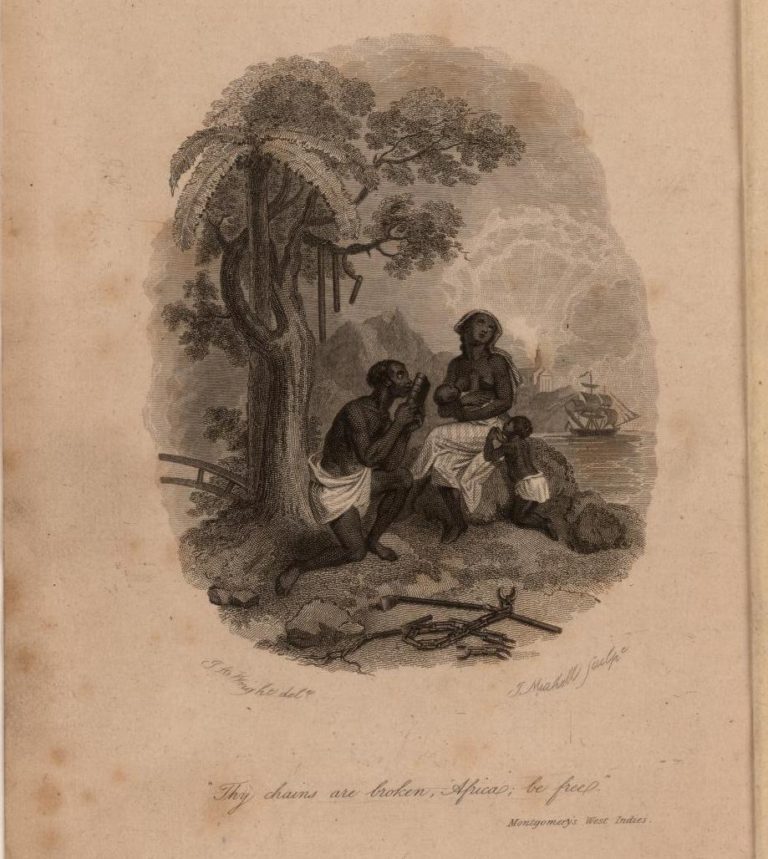

J.A. Wright, ‘Freed West Indian slave family’, The negro’s friend, or, the Sheffield anti-slavery album., J. Blackwell, Sheffield, 1826.

J.A. Wright, ‘Freed West Indian slave family’, The negro’s friend, or, the Sheffield anti-slavery album., J. Blackwell, Sheffield, 1826.

Anti-slavery activists also saw conversion to Christianity as central to emancipation. This image shows an idealised family, post emancipation, with the tools of slavery at their feet. The man holds a book, which looks like a bible, while the rays of light peeking through the clouds appear to symbolise the light of redemption. Some enslaved people also embraced Christian theology as a way to resist slavery. Biblical references to slaves finding freedom resonated strongly. Christianity also provided a powerful model to explain how suffering would be alleviated and their sacrifices would be rewarded.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free