Sustainability: Impact of Chemical Fertilizers

Share this step

In India there is now considerable debate about the future of farming as international conglomerates aggressively push forward mono-cultural practices using high-yield crops underpinned with the use of agrochemical fertilizers. This is threatening not only the livelihoods of small-scale farmers but also having an immediate and deleterious impact on the ecosystem itself.

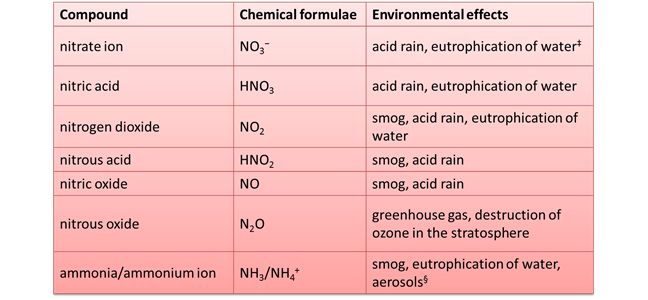

This apparent ‘need’ for chemical fertilisers to feed the large proportion of the world’s human population is now the major source of nitrates in the environment. This is having considerable environmental impact. Nitrous oxide is a significant greenhouse gas but there are also other environmental effects as shown in Table 1 below.

The increased use of nitrogen compounds in agriculture is also indirectly implicated in:

- Marked increase in the incidence of asthma in many developed countries.

- The formation of algal bloom which ‘choke’ lakes, rivers and streams. The blooms may contain a type of bacteria, called cyanobacteria, which produce toxins, killing water life and posing a threat to people

Above text and table sourced from OpenLearn under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence

A necessary evil

Many would argue that such chemical fertilisers are necessary if we are to feed a growing, frequently starving population. However, food is losing its flavour, the very make-up of the soil is being destroyed, and farmers are required to buy in fertilizers and thus find themselves exposed to the vagaries of the market. This is a sorry indictment of the impact of chemical fertilizers on the lives of producers and consumers, and on the land itself.

Back to basics

The first half of the 20th century saw the publication of a number of influential treatises which rejected chemical fertilizers and advocated more organic methods. We might pick out Rudolf Steiner’s 1924 lectures, published as Spiritual Foundations for the Renewal of Agriculture, which responded to the damage he perceived had been done to agriculture by ‘modern cultural and intellectual trends’.

Steiner’s suggestion for a more holistic approach, that emphasised the use of manure and planting according to lunar cycles, resonates with the earlier agronomic texts of Roman and Arabic writers. His treatise would become the basis of biodynamic agriculture. This, together with the works of others, led to the formation of the Soil Association in 1946, which remains the most important voice for the organic movement.

In the post-war period, in what might be described as a Malthusian ground swell, we have seen a return to more natural practices. This largely unchoreographed movement from below lies behind biodynamic farming, organic farming, local food, and slow food movement. What articulates the practice and philosophy of this amorphous group of individuals and organisations is a concern for the environment and the future of the soil. As a consequence those involved are increasingly discarding the chemical solution and returning to the very principles that guided farming throughout the pre-industrial era.

Food waste

Supermarkets are responsible for huge quantities of waste: shelves hold baskets of oranges, scores deep, hundreds of cartons of milk are on perpetual display and meat and fish counters bulge with pre-wrapped, oven-ready protein. A proportion of this food is never sold and while some supermarkets have signed up to food bank donations, large quantities of unspoilt but ‘past sell-by’, or slightly blemished items, are, literally, ‘dumped’.

‘Freeganism’ is an attempt to redress food wastefulness. Opposed to the routine waste of supermarkets and households, freegans seek to draw attention to the financial and friendly benefits of sharing wasted foods. Whilst freeganism is now a term used in common parlance, the message is still not getting through to the general public. It is estimated that nearly 30 per cent of the food Britons buy is wasted, with over 6.7 million tonnes being discarded uneaten.

The issue of waste, and perhaps more importantly, wastefulness, goes to the heart of global inequalities. As Tristram Stewart notes, ‘All the world’s nearly one billion hungry people could be lifted out of malnourishment on less than a quarter of the food that is wasted in the US, UK and Europe’. Moreover, a ‘third of the world’s entire food supply could be saved by reducing waste – or enough to feed 3 billion people; and this would still leave enough surplus for countries to provide their populations with 130 per cent of their nutritional requirements.’

The statistics of waste – food waste, packaging waste, electronics waste, wasted journeys – are shocking, and have economic, environmental and, perhaps increasingly, personal implications.

Above text sourced from OpenLearn under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Licence

What is rubbish?

In many Chinese cities street recycling is a way of life. Here ‘waste’ is a means for people to earn money to live. If they work hard (and are lucky) they make more money than if they had not migrated from their villages. Many cities have a steady supply of materials such as paper, corrugated card, plastics and metals. These are collected for recycling (that is, making into new items with a similar function). The recyclers will spend their entire day travelling around neighborhoods collecting and buying materials. Once they have collected as much as they can carry, they then take their load to depots where the waste is weighed out and money changes hands. In many cases the people collecting waste are rural migrants who have moved towards China’s coastal cities in search of a better life for themselves.

Conclusions

Attitudes to ‘waste’ reveal a lot about the cultures responsible for its generation (or not). Rubbish may be a focal point for communities, as in Prehistory when middens proclaimed wealth and fertility, or in modern Chinese cities where rubbish middens proclaim the opposite: poverty and ill-health.

Where connections are made between illness and waste, humans have gone to extraordinary lengths to ensure that ‘filth’ is jettisoned out of eyesight.

Many cultures have seen great feats of civil engineering to deal with waste, such as the sewer systems that were monuments to Roman and Victorian civilisation. However, as is the case with most short-term solutions, the problem was just passed down the chain (or drain) creating much larger long-term problems of water pollution and soil fertility.

Sanitation systems, for all the benefits that they have brought for human health, have also created a legacy of cultural neuroticism about ‘filth’, with communities discarding ever greater quantities of ‘rubbish’ (or perfectly good food) that ought to be used to bring others out of starvation.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free