Swiss–EU Law: A Disparate System

The present article deals with certain aspects of the institutional system of the Swiss–EU agreements that led the EU to suggest changes. As a starting point, it must be remembered that the system as a whole has developed over time. There are now many agreements and it is perhaps no wonder that they reflect different approaches to issues such as the development of the law, its interpretation and the settlement of disputes. Indeed, it would be surprising if an agreement of the 1970s and an agreement of 2004 were to provide for the same approach in this respect. Our first message is, therefore, that institutional rules in the various agreements are of a rather disparate nature.

Interpretation of the bilateral agreements

With respect to interpretation, the general rule is that of Art. 31 of the Vienna Treaty Convention of 1969, according to which ‘a treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose’.

In addition to this, two bilateral agreements contain specific interpretation rules, namely the Air Transport Agreement (Art. 1) and the Free Movement of Persons Agreement (Art. 16(1)). Both provide that insofar as their provisions are identical in substance to corresponding rules of the Union, they must be interpreted in conformity with the relevant decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) given prior to the date of signature of the agreement in question. For the Agreement on the Free Movement of Persons, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court has decided that, in principle, a parallel application is called for even beyond the date of signature of the agreement (BGE 136 II 5). For the Air Transport Agreement, there is no corresponding case law (yet) – apparently because no case so far has raised this issue.

Dispute settlement and supervision

With respect to the settlement of disagreements between the parties, the general rule is that the relevant Mixed/Joint Committee is in charge. These Committees are bodies in charge of monitoring the functioning of the agreements. Both the European Union (EU) side and the Swiss side are represented in that framework. The problem is that here a dispute can get stuck, as happened with the 8-day rule. It is therefore possible that, over a prolonged time, the parties get no further than ‘to agree to disagree’. Notably, the agreements do not provide for a judicial element that would allow for the settlement of the dispute before a court.

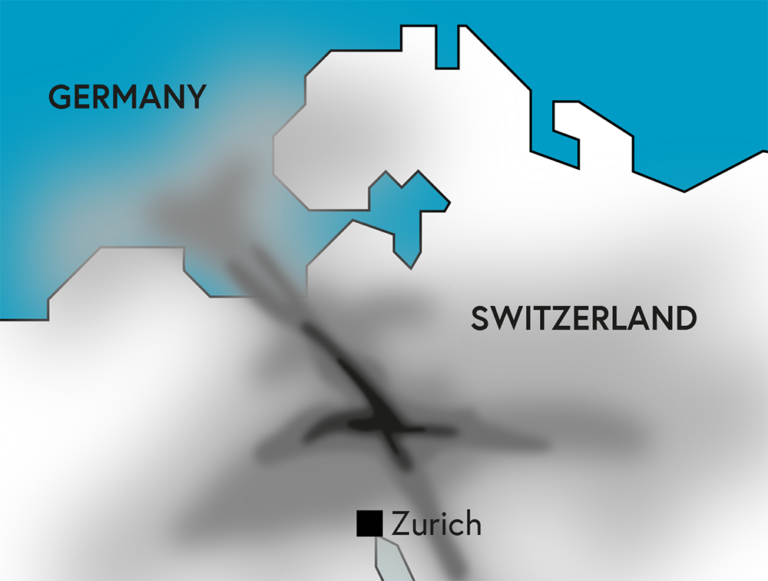

The only exception is the Air Transport Agreement. Under its rules, the European Commission and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) are in charge for certain types of issues. A few years ago, this became relevant in a dispute between Switzerland and Germany relating to German rules on the reduction of noise caused by airplanes taking off from, and landing in, Zurich Airport.

A map that shows the strong traffic of airplanes around Zurich

A map that shows the strong traffic of airplanes around Zurich

This case first led to a decision by the Commission and then, when Switzerland disagreed with it, to decisions by two levels of the Court of Justice. [1]

International and independent supervision

Different from EU law and European Economic Association (EEA) law, the Swiss–EU Agreements do not provide for a mechanism of independent international supervision with administrative and judicial procedures. In other words, under the agreements there is no international body with the power to investigate breaches of the parties’ obligations and to take a State Party to an international court over this issue.

Development of the law

Finally, international agreements are not set in stone. Rather, they can be changed through a procedure that is usually described in the relevant agreement itself. That in itself is not a ‘difficult’ issue. However particular questions arise where an agreement provides for the association of a third country to certain EU policies. Should that law develop in parallel with the EU law from which it is derived? In other words, should such agreements be dynamic even in their legal nature?

In the system of the Swiss–EU agreements only the Schengen, Dublin and Customs Agreements are based on the principle that they should be updated regularly, failing which there are legal sanctions. For example, we will see in our next step that a refusal to accept an update to the Schengen Agreement in principle leads to its termination. Note, however, that updating is never automatic but rather requires a decision of Switzerland to that effect.

All other agreements are what is sometimes called static in nature. This does not mean that they cannot be changed or updated. In fact, in the case of some ‘static’ agreements changes happen quite regularly. However, static agreements do not provide for legal sanctions for the case where an update is not accepted by Switzerland.

A note for advanced learners of public international law

The Vienna Treaty Convention applies only to its members, which are states, thus excluding the EU, which is an international organisation. However, the Vienna Treaty Convention to a great part is considered to be reflective of customary law. Further, there is another Vienna Convention, namely the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties between States and International Organizations or between International Organizations of 1986. This second Convention copied Art. 31 of the Vienna Treaty Convention. However, the second Convention (ie the Vienna Convention that also includes international organisations) has not entered into force so far, and the EU has not signed it.

Further reading

The charts in the ‘downloads’ section provide further information about the adaptation and revision of the Swiss–EU agreements as well as about their interpretation and about the role of the Joint/Mixed Committees:

- Chart Bilat15 provides more information about the revision of the Swiss–EU Agreements.

- Chart Bilat16 provides more information about the interpretation of the Swiss–EU Agreements.

- Chart Bilat17 provides more information about the role of the Mixed/Joint Committees, including in the context of dispute settlement.

Read the decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union on the German–Swiss dispute on air noise (Case C-547/10 P Swiss Confederation v Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2013:139).

References

[1] (Case T-319/05 Swiss Confederation v Commission, ECLI:EU:T:2010:367, and Case C-547/10 P Swiss Confederation v Commission, ECLI:EU:C:2013:139).

Share this

Switzerland in Europe: Money, Migration and Other Difficult Matters

Switzerland in Europe: Money, Migration and Other Difficult Matters

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free