Impact of grazing on the final product

Share this step

Regenerative agriculture brings together and reconciles two of the crucial challenges facing the world: that of producing adequate and nutritious food, on the one hand, and that of restoring ecosystems degraded by human activity, on the other.

The impact of regenerative practices on soil and environmental health has been developed throughout this course. However, this type of agriculture promotes a holistic view of the agro-livestock sector by also promoting better nutrition and human health.

Evolution of human nutrition

Industrialisation and centralised food production were created to increase the ability of farmers to produce more food at a lower cost, thus enabling higher crop yields through increased mechanisation, use of inputs and genetic improvement. Unfortunately, an essential principle was lost in this efficiency equation: that of food quality and nutrient density.

One of many examples is seen in the research of August Dunning, chief scientist and co-owner of Eco Organics, as he reveals that to get the amount of iron you used to get from an apple in 1950, by 1998 you would have to eat 26 apples. Today you would have to eat 36 apples to achieve this, and this is a direct consequence of industrial farming techniques and the use of chemicals that destroy soil quality by killing essential microbes.

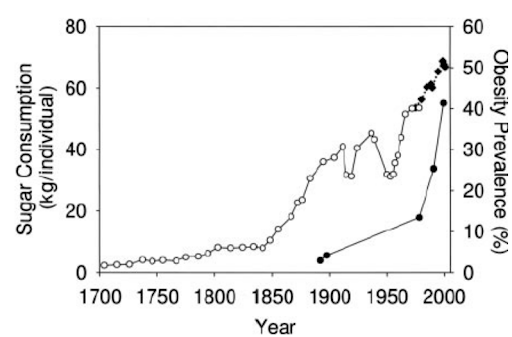

This soil degradation is compounded by society’s consumption habits, which tend to consume much more processed food, fats and sugars. This encourages the development of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and intolerances (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Sugar intake per capita in the United Kingdom from 1700 to 1978 (〇) and in the United States from 1975 to 2000 (◾) is compared with obesity rates in the United States in white men aged 60 – 69 y (⧭). Source: The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2007

Figure 1: Sugar intake per capita in the United Kingdom from 1700 to 1978 (〇) and in the United States from 1975 to 2000 (◾) is compared with obesity rates in the United States in white men aged 60 – 69 y (⧭). Source: The American journal of clinical nutrition, 2007

Conventional agriculture and human health

More than half of the world today suffers from “hidden hunger”, a condition defined by a deficiency of micronutrients despite adequate daily caloric intake.[1] This “hidden hunger” may be part of the rise in chronic disease in the US as we rely on vitamins, minerals, protein and food – not calories – to prevent disease.

Agricultural production goals focused primarily on maximising crop yields have led to a significant decline in nutrient concentrations over the past 50-70 years.[3] An assessment of nutrient concentrations of 43 crops, mainly fruits and vegetables, from 1950 to 1999 revealed a decline in most nutrients – protein, Ca, P, Fe, riboflavin and vitamin C – decreasing significantly, ranging from 6% to 38%.[4] The same study also revealed higher concentrations of water and carbohydrates in our food.

Although cereal yields have more than doubled in this time period,[5] the protein concentration of grains have decreased significantly: wheat, rice and barley by up to 30%, 18% and 50%, respectively.[6]

This suggests a “dilution effect”, an inverse relationship between yields and a measured nutrient. This effect is cause for concern, as more than half of the world’s population suffers from nutrient health deficiency,[7] and grain products constitute an important part of many diets.

More recently, climate change – driven in part by emissions from the production and use of fertilisers, herbicides and agricultural pesticides – has been implicated in declining crop nutrition.[8] Indeed, studies found that increased atmospheric CO2 levels in rice fields reduced the concentration of protein, iron, zinc and B vitamins.[9]

Considering the health implications of a continued decline in crop nutrient density, agricultural production goals will have to shift from an exclusive emphasis on yield to a more integrated emphasis on crop quality. Regenerative organic agriculture and its emphasis on soil health supports this shift.

Grazing and its impact on human health

The previous step detailed the benefits of pastoralism* in terms of environmental and soil health. The aim of this section is to transfer the discourse to human health and, more precisely, to the nutrient density of products from pastoral systems.

To this end, EIT Food has carried out a comparative study in which the fatty acid profile of meat from a number of animals intended for human consumption has been analysed. These meat samples can be classified into two groups: the first group is made up of animals from different farms that have been fed only pasture and fodder and a second group of animals from different farms that have been fed with different proportions of feed and fodder.

The percentage of saturated fats (SFA) was slightly higher in grass-fed animals. This can be explained by the state of maturity of the pasture, which can lead to an increase in SFA, since fibrous feed (over-mature pasture) favours the formation of these fatty acids.

In the case of Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFAs), animals coming from the grazing systems had lower levels than the animals fed on feed and forage. This is because green grass is poor in MUFAs compared to cereals, which have a higher proportion.

Regarding Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs), the percentage of these acids is much higher for animals fed with pasture and forage, than for animals fed with concentrates, which is desirable for our cardiovascular system, but it is also true that the variability of results in grazing animals is very high. This variability is explained by the different level of maturity of the grass consumed by animals. This statement leads us to consider the importance of using grass at its optimum time, before the stalks reach a high fibre content.

Higher levels of omega-3 fatty acid were found in the grass group than in the feed group. This is very desirable as this is the main objective sought with grass and forage feeding. The high omega-3 fatty acid content in the meat of grass-fed animals is explained by the high omega-3 content of green plants and the low level of this fatty acid in the cereals that make up the feed.

If we analyse the effects of grazing on another product such as milk, we find similar results. In fact, the Lactiker Research Group of the University of the Basque Country published an international thesis on the benefits of grazing and its influence on the nutritional quality of milk.[10]

One of the most interesting aspects of this research is that the study has been carried out with commercial sheep flocks. The results show that extensive mountain grazing favours:

- A milk fat profile with a lower content of saturated fatty acids, including those considered atherogenic (formation of fatty deposits in the arteries)

- A higher content of fatty acids that are desirable from a nutritional and human health point of view, such as α-linolenic acid (n-3), rumenic acid (conjugated linoleic acid), vaccenic acid (trans n-7) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, n-3).

Likewise, mountain grazing also increases the tocopherol content of milk and cheese from commercial herds when compared to management of these herds in stalls during winter and part-time grazing in the valley in spring.

As for the results derived from the study of volatile compounds (responsible for cheese aroma), relevant changes were observed in the content of various compounds such as acids, esters, ketones, aldehydes and terpenes, when the sheep were in mountain grazing.

Sensory analysis of the cheeses, carried out by a trained panel of tasters, showed no significant differences in taste, odour and texture properties between mountain cheeses compared to valley or winter grazing cheeses when the cheeses were made by the same shepherd during the annual cheese production season.

*Pastoralism: a form of animal husbandry where livestock are released onto large vegetated pasture lands for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The animal species involved include cattle, camels, goats, yaks, llamas, reindeer, horses and sheep.

Conclusions

With current scientific knowledge, it is clearly demonstrated that products obtained from animals fed only on pasture and forage have a positive effect on the health of consumers. Some parameters have a clear impact on our health, such as Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA), which are almost twice as high in animals fed on pasture and fodder as in animals fed on concentrates.

The information obtained in this research shows the nutritional benefits of eating meat and milk produced from grazing animals. Moreover, from an economic point of view, the consumption of these products can contribute to the development of the rural landscape, especially with regard to the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystems, thus promoting the establishment of a resilient and sustainable system.

Let’s discuss

- Are you surprised by the results of the study?

- Do you already purchase food produce that comes from graze-fed animals or will the results of this study affect your future food choices?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free