Agroforestry

Share this step

Agroforestry is a farming system that combines trees and agriculture (crops or livestock) on the same land. These different elements complement each other.

This leads to higher resilience, greater biodiversity and more productive use, compared to a monoculture system.

The overall result is very positive, as the system allows the production of vegetables, grains, fodder and other raw materials from crops, together with timber and fruits from trees. This multiplicity of products allows farmers to access different markets, ensuring sustainable yields.

In the European Union, agroforestry is defined as “land use systems in which trees are grown in combination with agriculture on the same land”.[1] A more detailed definition of agroforestry is “the practice of deliberately integrating woody vegetation (trees or shrubs) with crop and/or animal systems to benefit from the resulting ecological and economic interactions”.[2]

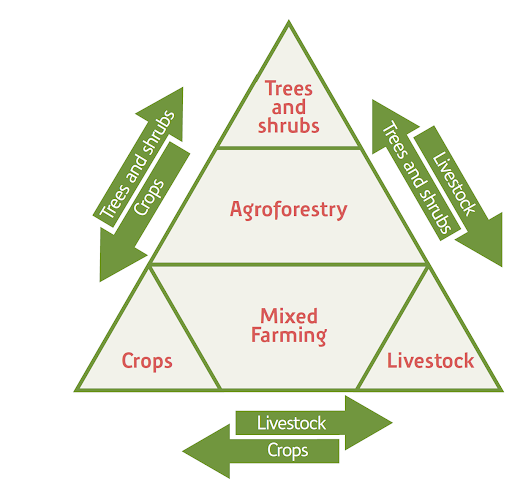

Whereas “mixed farming” is the integration of crops and livestock, agroforestry covers the area in a triangle where trees (and shrubs) are integrated with either crops, livestock, or mixed farming (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Agroforestry involves the integration of trees and shrubs with either crop, livestock or mixed farming. Source: Agroforestry handbook, Ben Raskin and Simone Osborn 2019

Figure 1: Agroforestry involves the integration of trees and shrubs with either crop, livestock or mixed farming. Source: Agroforestry handbook, Ben Raskin and Simone Osborn 2019

A recent agroforestry research project called AGFORWARD[3] identified five distinct types of agroforestry in Europe:

- Silvo-pastoral agroforestry: the combination of trees and livestock;

- Silvo-arable agroforestry: the combination of trees and crops. If livestock is included, the word used to describe this type of system should be agrosilvopastoral;

- Hedgerows, shelterbelts and riparian buffer strips. Lawson et al. refers to them as “linear” forms of agroforestry where trees are grown between parcels of land;

- Forest farming: crop cultivation within a forest environment; and

- Homegardens: combination of trees and food production close to homes.

What are the benefits of an agroforestry system?

Improve soil health

One of the main objectives of regenerative agriculture is the regeneration of soils, improving their health and fertility. Agroforestry allows, through trees, to maintain the long-term soil fertility of pastures thanks to the increased number of earthworms, fungi and bacteria that restore soil activity.

Trees capture nutrients leached below the grass rooting zone and return them to surface soil via litter and root turnover. They improve the soil’s holding capacity for water and nutrients thanks to the establishment of a deep root system. They also limit compaction by animals (poaching) and increase infiltration.

Under elevated stress conditions (such as drought) trees invest in their mycorrhizal associations and can scavenge water and nutrients from deeper within the soil. The same is true under elevated CO2 conditions, suggesting that trees also help resilience to climate change. In addition, trees’ root systems significantly reduce soil loss from erosion.

*Mycorrhizal associations: A mycorrhiza is a symbiotic association between a fungus and a plant.

Reducing the risk of pests and diseases

Systems with several species are less vulnerable to diseases and pests than monocultures. This is because flowers are present for as long as possible to ensure food and host sources are available for beneficial or predatory species that can help managing pests and diseases.

Planting trees in wetter areas of the farm can also provide additional health benefits to livestock. These areas are often only marginally productive. Fencing them off helps with managing stock. Trees will naturally dry soils creating conditions that are less favourable for bacteria that cause foot rot or snails that form part of the liver fluke cycle.

Whilst trees can increase risk of head flies and blow flies (by offering a habitat for them), in a well-designed silvo-pastoral system there are also more dung beetles. These remove faeces more quickly and combined with higher predator numbers can result in fly counts that are 40% lower than on open pasture. However, drying wetlands can have an impact on biodiversity. It is important to do an ecological survey if major plantings are planned.[4]

Reduction of heat stress

Overheating in crops and livestock can have a significant impact on productivity. Seeking shade or shelter are natural and effective animal behaviours and, in silvo-pasture where solar radiation can be reduced by as much as 58%, skin temperature is 4ºC lower than on open pasture.[5] As a consequence, other normal behaviour patterns such as eating and resting are better maintained.

In areas with limited shading opportunities livestock will tend to clump (increasing the risk of disease, soil compaction and death of vegetation), so provision of more even-shade using silvo-pasture can reduce this effect.[6]

Broader environmental benefits

Trees provide a set of much broader environmental benefits than just to the farm itself. Expanding the area of silvo-pasture, for example, will sequester significant amounts of carbon (C). These are higher in silvo-pastoral systems than they are in silvo-arable. Silvo-pastures can also provide biodiversity benefits. It is associated with higher soil biodiversity and provides semi-natural habitat and habitat networks for a range of birds, mammals and other fauna.

All of these interactions provide societal benefits which policy should support. These can benefit the farm through access to environmental grants through agri-environmental schemes.

Photo by PROJETO CAFÉ GATO-MOURISCO on Unsplash

Photo by PROJETO CAFÉ GATO-MOURISCO on Unsplash

Design and planning of an agroforestry system

“What is not defined cannot be measured. What is not measured cannot be improved. What is not improved, always degrades”.

This phrase coined by William Thomson Kelvin, British physicist and mathematician (1824-1907) highlights the importance of measuring data in order to improve. This concept is perfectly applicable in our case and we will now see how this can be done.

Before designing or establishing new species, it is important to take contextual factors into account. This includes:

- The environmental conditions and corresponding climatic indices that will allow choosing species adapted to the environment;

- The location and situation of the farm (hillside or slopes, possible industrial activities nearby, etc.);

- The availability of water and the possibility or not of irrigation; and

- The type of soil and its characteristics (pH, texture, depth, granulometry, etc.).

In addition, the social and cultural context of the area such as traditions, local market potential, access to infrastructures such as oil mills, cooperatives, sawmills, etc. must be taken into account. All these factors influence the design and decision making of the system established in the farm.

It is essential to determine the objectives that lead to the establishment of an agroforestry system. Any form of diversification is a challenge, so it’s important to establish clear and measurable objectives in order to design the most efficient and profitable model. They must be based on the results of benchmarking and always taking into account the socio-economic environment of the farm. Some of these objectives could be:

- Diversify sources of income and reduce the risks of monoculture;

- Improve biodiversity of the farm to attract new fauna;

- Improve water retention; and

- Increase soil fertility, etc.

The second step would be to quantify these objectives. It can be done from an different points of view, (i) agronomic, such as yield or amount of biomass generated per unit area. (ii) Economic, such as reduction in total inputs or economic profitability. And finally, (iii) they can also be social, such as the creation of local employment.

Once the objectives have been established and quantified, land design can begin. There are no limits on what species can be brought together in agroforestry if the site is suitable and mitigating measures are made, however the following guidance is useful:

- Species may harbour pests or disease which could infect an adjacent species, e.g. rhododendron fungal diseases can affect larch

- Trees with late leafing and or short leaf area duration may be optimal in some systems

- Variety is critical for fruit and nut trees. Grafting can dramatically improve precocity (age of bearing)

- Different breeds of sheep have different bark-stripping behaviours

The agroforestry diagnosis and design focuses on the analysis of the perennial woody component, its interactions with other productive components, its management and its use by the farm that manages the land.

To this end, the farm is considered as a system in which humans, production systems and the environmental and economic environment interact. There is no single model; it has to be adapted to each farm.

Let’s discuss:

- Think about your region, have you seen examples of agroforestry in practice?

- In some regions coffee, cocoa, rubber, and oil palm are grown as part of an agroforestry system. In your region, which tree species could be productive and used in agroforestry?

- What do you think could be some possible pros and cons to silvo-arable and silvo-pastoral agroforestry?

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free