A case on metal mining and reindeer herding: Boliden in northern Sweden

Share this step

Following the introduction of the resource based approach, you can find information on a SUMEX case study below. This case illustrates that effective Land Use planning can consolidate competition for Land Use and solve potetnial issues that can arise from extractive projects.

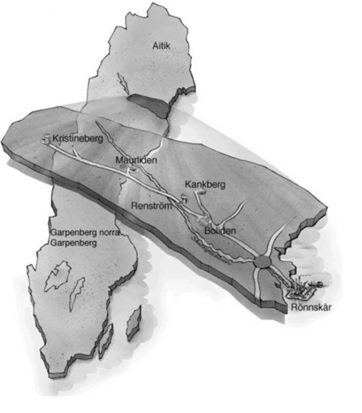

Getting to know the Boliden area

Mineral extraction in the Boliden Area started around 100 years ago. Currently, it has one closed mine at Maurliden and three operating mines: Renström, Kankberg and Kristineberg, 1 Concentrator (Boliden Area Operations Processing Plant) and a Smelter at Rönnskär (Albrecht, 2018; Boliden AB, 2021d)

–>Table 1: ‘Basic characteristics of Extractive operations in Renström, Kankberg and Kristineberg Mines’ from the word document needs to be included here as an image [-> how can we include images in the text?]

Reindeer herding & Sami People and what it means for mineral extraction

The intersection between mineral extraction and indigenous people’s rights has become an increasingly contested topic in geographies where these activities overlap. The indigenous people of Sweden are the Sami people, located in the northern Scandinavian Peninsula and Kola Peninsula; a territory shared between Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia. The traditional Sami land located in these four countries are referred to as Sápmi1. There are about 20,000 Sami people living in Sweden, of which about 3,500 are reindeer owners, owning about 220,000 reindeer (Jacobsson, Stoor and Eriksson, 2020). Sami people domesticated reindeer in the 17th century. Since then, reindeer herding constitutes a central part of the Sami culture, albeit only a little over 10% of Sami people are reindeer herders due to the challenges of the reindeer trade, including disputes over land rights and loss of grazing land (The International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry (ICR), no date). Reindeer herding is organized in Reindeer Herding Communities, otherwise referred to as Sami villages (Sameby); there are a total of 51 Sami villages in Sweden. The majority of Sami people are not part of a Sameby, as a result of not owning reindeer, and are legally on equal footing with other Swedish citizens (Sametinget, 2022).

Boliden Area operations are situated within a number of Sami villages. Renström and Kankberg mines, and Boliden Concentrator are located within Mausjaure Sami village, whereas Kristineberg mine is located in Malå Sami village and Gran Sami village. The table below summarizes some general information on these villages:

-» Table 2: ‘ General information on the Sami villages overlapping with Bolidean Area mines and concentrator’ from the word document needs to be included here, how do we inlcude images in the middle of the text?

A rules system regulating Reindeer herding as a resource

The evaluation of the Institutional Regime that regulates reindeer as a resource requires an understanding of the ‘extent’ and ‘coherence’ of the regime in place. In this case, the ‘extent’ refers to the extent to which reindeer are affected by all different users (actors) that affect this resource. The analysis of reindeer herding in Sweden, in general, as well as in the Boliden Area, reveals that there is not a clear picture of the overall cumulative effects of different developments on reindeer herding. Although there are some positive initiatives from the company, which seeks to improve the understanding of the impact that specific projects have on reindeer grazing patterns, the scope of such studies does not go beyond measuring the impact of one specific project and cannot estimate whether the cumulative effect on reindeer threatens the reproductive capability of this resource. In terms of coherence, the Environmental Code requires the Land and Environmental Court to make a decision balancing out national interests, in this case between an extractive operation and preserving intact habitats for reindeer, based on the public interest associated with different forms of land use.

However, the assumption that any mineral extraction project is in the interest of society is far from true. UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples maintains that expropriation for the sake of national interest is not a legitimate argument in cases concerning commercial activities when private profit is involved (Lawrence and Larsen, 2019). In addition, the extent to which the renewal capacity of reindeer is affected by new developments is discussed only if it constitutes arguments of a representative party in the court hearing (this could be affected reindeer herders or county administration board). Hence, there is no in built process that evaluates the limits of the resource from the perspective of defining the maximum ‘stocks’ of the resource that can be affected without causing irreversible damage.

Reindeer herding is not inherently adaptable, and, in many cases, coexistence with other land uses, such as extractives, is not possible. Evaluation of issues concerning reindeer herding on a case by case basis can lead to a failure in accounting for the cumulative effect that different uses (mineral extraction, transport infrastructure, energy production) and users (different mineral extraction operations in one village) may have on the resource as a whole. Without a thorough understanding of this bigger picture, decisions made by institutions that regulate different uses affecting reindeer (the institutional regime) can be incoherent with reindeer conservation goals. Another area of internal incoherence is within the property rights system, concerning the Usufruct rights held by reindeer herding Sami people.

Although such rights are endowed upon reindeer herders by the Swedish Constitution, in the form of special rights to property (usufruct), reindeer herders affected by permitting of exploration/exploitation activities are not legally subject to compensation. The compensation of affected property owners and the lack of any compensation for Usufruct holders whose use rights are affected indicates a differentiated protection of property rights, and raises concerns of legitimacy and justice of such provisions. In conclusion, the institutional resource regime regulating reindeer can be classified as a complex one, which regulates the uses that affect the resource to a high extent, but with coherency flaws.

A Synthesis of how reindeer as a resource is affected by mineral extraction

The analysis of reindeer herding in Sweden, in general, as well as in the Boliden Area, reveals that there is not a clear picture of the overall cumulative effects of different developments on the reindeer. The ‘slicing’ and ‘dicing’ of the reindeer issue into project-based evaluations confines the scope of each evaluation and fails to recognize the environmental limits of reindeer as a resource, that the resource is not inherently adaptable, and that interventions in reindeer grazing areas (especially winter pastures) should be minimized and strategically thought through in their entirety and not on a case to case basis. Reindeer herding rights, connected to land use rights (usufruct), are protected by the Swedish Constitution. However, such rights are not subject to any form of compensation when infringed by other land uses, such as extractives. With an expanding bundle of rights, including water rights (following the Supreme Court decision that the Girjas Sameby may grant small-game and fishing rights without the consent of the State), there is a need to clearly define what these rights mean and how they are protected, or otherwise compensated, fairly. Parts of the institutional regime regulating reindeer resources, both in public policy and property rights regulations, are often incoherent with reindeer conservation goals, reflecting a complex institutional regime.

A complex regime, so what: Thoughts by our experts

Given the challenges on mineral extraction and reindeer herding from an IRR perspective, we provide you with some suggestions on how to improve the situation.

There is a call for a shift in the institutional regime regulating reindeer to grant Sami communities more power in decision-making. To this end, clear guidelines for consultation with Sami people should be established. The duty of consultation should not only remain with the company, but it should also involve public authorities. Prior to consultation, the interested exploration/exploitation parties should draft a report of the planned operations and the way they will affect reindeer husbandry together with impacts on landscape, culture, hunting and fishing.

To ensure that the cumulative effect of different interventions are taken into account, the public authorities evaluating permits for exploration should take into consideration previously approved exploration permits in the same Sami district and their collective impact.

So we gave you some practical insights on the topic. We would be interested in what you think about:

- How useful is the IRR approach to investigate mineral resource conflicts with other resources regimes?

- Do you have experience with resource conflicts around extractive projects? If yes, who are the resource owners, users, and what are the conflicts?

Further reading material: SUMEX project report D3.2 Draft Report Policy Analysis

Share this

Sustainable Management in the Extractive Industry

Sustainable Management in the Extractive Industry

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free