How Do Clinical Trials Work?

Share this step

To test potential new treatments we need clinical trials – often called ‘drug trials’. These are controlled tests, strictly carried out to try as much as possible to ensure any differences that are seen are due to the drug being tested and not caused by any other factors that could alter or affect the true result.

In order to hold these treatments up to the highest scientific standards, and thus give the most reliable results, there are several factors that are considered to be ‘gold-standard’ for running a drug trial. Where possible trials should be placebo-controlled, randomised, and double-blind.

Let us explore each of these terms in a little more detail:

Placebo-controlled – a placebo is ‘dummy treatment’ designed to look exactly like the real therapy being investigated but containing no active treatment. In the placebo arm of the trial, people complete absolutely all the same steps as someone taking the actual drug. This is the best way to compare the rigorousness of the drug and make sure that nothing about the trial design itself is affecting the outcome. Or indeed just the nature of being in a trial in the first place – known as the placebo effect.

Randomised – in a randomised trial participants will be randomly allocated to receive either treatment (possibly also being randomised to one of several doses being tested) or placebo. Randomness is an important factor because it is designed to balance out the natural variation that will exist between individuals, which could in theory affect the outcomes being measured in the trial.

Double-blind – in a double-blind trial neither the participant taking part nor the research staff administering the treatment and conducting the assessments, know whether an individual is getting the active treatment or the placebo. This is really important so no one can be unconsciously biased by the knowledge of who is and who isn’t receiving the drug – and the expectations that may come along with that knowledge.

Clinical Trial Phases

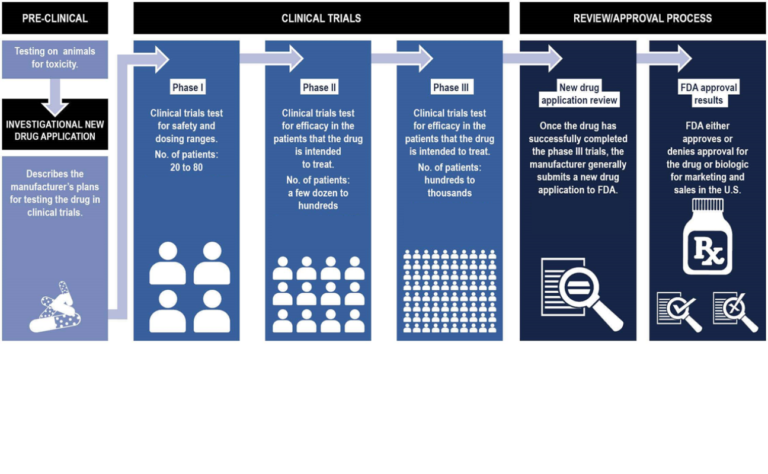

There are several checkpoints or phases that a drug must successfully pass on its journey to becoming widely available for use. Preliminary testing will use animal models to check safety and maybe look for hints at effectiveness in these animal models that try to recreate the disease.

Phase 1 – is primarily concerned with the safety profile of the drug. Sometimes these trials are described as ‘first in man’. Phase 1 trials assess if the drug is well tolerated and check for side effects. This is also the phase to start to work out the most effective dose. Phase 1 trials involve only a handful of people and so are too small to tell if the drug is effective.

Phase 2 – starts to explore the effectiveness of the drug. This is done by evaluating pre-specified outcome measures – things which should change in a positive way if the drug is working as intended. In Alzheimer’s trials scores on certain cognitive tests or improvements in independent functioning have traditionally been used to measure outcome. There is a movement however to start also measuring effectiveness by evidencing desirable changes in target biomarkers. Phase 2 trials are carried out in still fairly small numbers of participants – in the hundreds rather than thousands. The aim of a phase 2 trial is primarily to collect enough data to decide if the drug is worth pursuing a larger (and much more expensive) phase 3 trial.

Phase 3 – the real test to see if the new treatment works. Phase 3 trials often involve thousands of participants and are often conducted across several countries. Phase 3 trials are all about proving the drug is effective in improving the set outcome measure and often that the new drug being tested is as good, or better, than the existing treatments. The results of phase 3 testing will provide the best evidence for whether a drug should go on to be licensed. If phase 3 trials are considered ‘positive’ – they meet their pre-determined criteria – then applications will be made to the relevant regulatory authorities for example, the FDA in the US, EMA in Europe and MHRA in the UK. An expert panel then consider the sum of all the evidence collected throughout the trial stages and deliver a decision on whether the drug can be approved or not.

Phase 4 – following approval of the drug by the regulatory authorities, phase 4 trials look to gather more long-term data on effectiveness and side effects once the drug is being used in the ‘real-world’.

FDA approval process (Click to expand) figure adapted from U.S. Government Accountability Office review of the FDA approval process

FDA approval process (Click to expand) figure adapted from U.S. Government Accountability Office review of the FDA approval process

Clinical Trials for Alzheimer’s Disease

The most recent drug to be approved for use in Alzheimer’s dementia was memantine back in 2002. And remember whilst we have a small number of drugs for symptomatic treatment, we have no disease-modifying therapies – drugs that actually tackle the underlying disease process.

If we imagine the damage caused by Alzheimer’s disease in the brain is equivalent to a boat springing a leak. The drugs we currently have act to bail water out of the boat. But they don’t do anything to plug the hole. Plugging the hole is the aim for disease modifying therapies.

Since 2002 over 2000 clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease have been undertaken across all phases. Each have unfortunately fallen at one hurdle or another and we still await the next successful therapy.

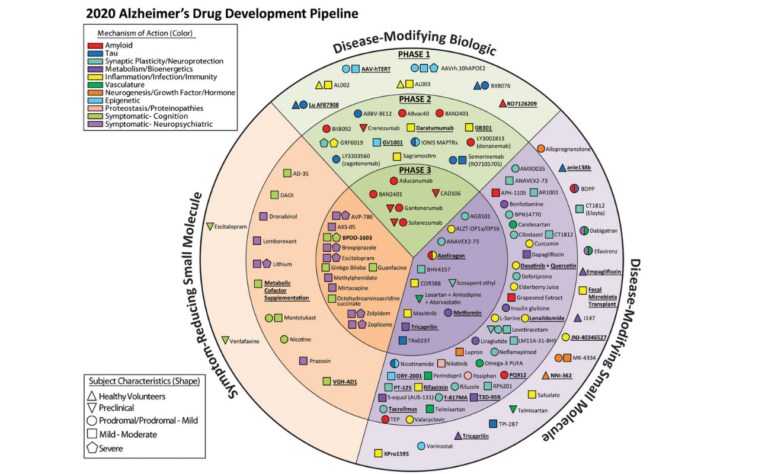

Since 2015 researchers led by Jeff Cummings at the Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health, Las Vegas have compiled an annual report, the Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline which catalogues all of the drugs currently in therapeutic trials. The current pipeline (as of Feb 2020) identifies over 200 different compounds – see chart below.

Drug development pipeline (Click to expand) Taken from Cummings et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2020. Underlined compounds are those newly registered since the 2019 report. (Figure by Mike de la Flor)

Drug development pipeline (Click to expand) Taken from Cummings et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2020. Underlined compounds are those newly registered since the 2019 report. (Figure by Mike de la Flor)

Let’s re-join Craig now and explore some of the reasons previous drug trials may have failed and how we can design better trials to find drugs that will help prevent and treat the diseases that lead to dementia.

Share this

Understanding Brain Health: Preventing Dementia

Understanding Brain Health: Preventing Dementia

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free