Wonkhe @ Home: The New Normal – What will it look like and how will universities get there?

Author: David Avery, Partnership Manager at FutureLearn

With September rapidly approaching and the world in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, I attended Wonkhe’s remote session on what ‘the new normal’ may look like for universities from next term. What will the student experience look like for those who decide to keep their places? How far will universities be able to meet student expectations while keeping everyone safe? And how will decisions get made in the context of the rapidly changing global pandemic? Don’t expect easy answers to any of these questions.

The event took the format of a presentation by Jim Dickinson, Associate Editor at Wonkhe, followed by a panel discussion with Mary Stuart, Vice Chancellor of the University of Lincoln and Jonathan Grant, Vice President of King’s College London.

Student Experience

If you’re a graduate, try to cast your mind back to the decision making process you went through before deciding to go to university and why you chose one institution in particular. What questions did you ask yourself? What were your hopes and aspirations for your university experience? What impact did you hope it would make on your life? How did you balance the importance of learning with the quality of the student union, the vibrance of the local nightlife and the chance to make lifelong friends and colleagues? Would university change or even help define your identity? It was probably hard to balance these sometimes competing motivations. Imagine having to make those decisions now. The way in which you answer, may give some clues as to what’s going to happen this September and beyond, when students face their first big choice about how they will approach their education in a post-covid world.

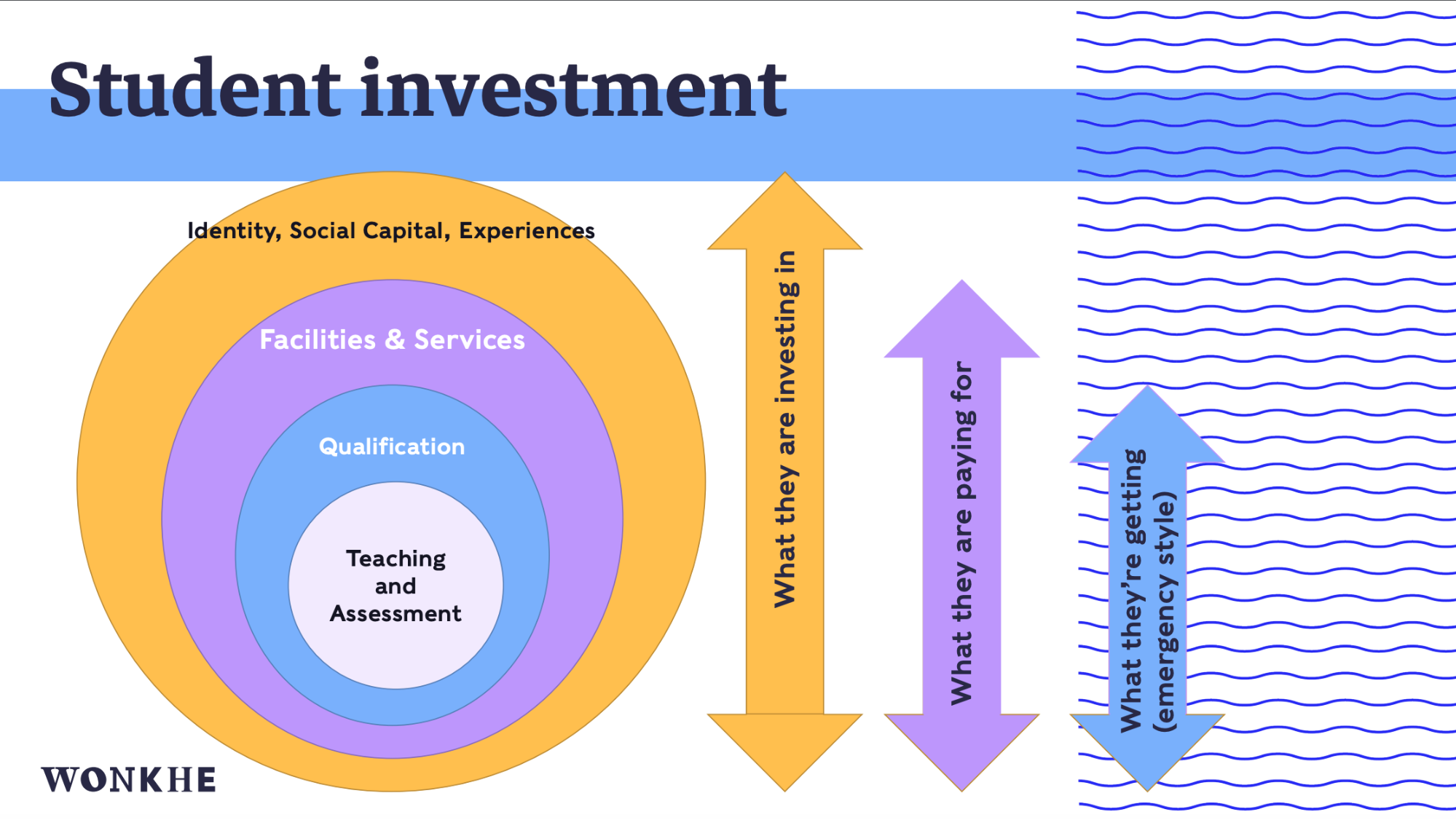

Jim Dickinson raised this as a central question in the challenge to find a new normal. When students invest in a university course, the value proposition goes far beyond teaching, learning and assessment and ultimately a qualification. They also pay for facilities and services that, when combined with tuition and the social experience, lead to the broadest but least tangible (and measurable) benefits of identity, social capital and life changing experiences. For different universities, the value of each ring of the concentric circle is different. Students at The Open University, for example, will have a different conception of university value compared to those attending a campus university.

But regardless of model, it will be hard for universities to claim students will be getting much beyond the core functions of teaching, assessment and a qualification this autumn. Panel members, Mary Stuart and Jonathan Grant, were in agreement that for universities to survive the pandemic, they need to move beyond metrics, become much more empathetic to the needs of students and to take their real feelings into account when designing university experiences for the post covid-19 world. And they need to have a true understanding of the diversity of experiences, motivations and challenges faced by the student population. A second year, full time, well funded 19 year old will have a completely different set of challenges from those of an overseas student with travel restrictions, competing life priorities and access to adequate IT equipment.

As Jim highlighted, while furlough schemes are in place, the economic impact of the pandemic has not yet been fully felt. We don’t know who will still be able to afford to go to university, we don’t know what drop out rates will be, we don’t know the impact of immigration and travel restrictions and we don’t yet know which programmes might be more impacted by these changes than others. Just as important as teaching and assessment, it’s what students will do with their other 120 weekly waking hours that might come to define the future of higher education. If they will be spending them inside cramped halls of residence, unable to leave and take advantage of university facilities, fully online degrees might look more attractive.

Online

Universities have had to rapidly shift their teaching, learning and assessment online. For many this is an acceleration of digital transformation programmes already running, for others it’s more of a rude awakening in the value of digital education. Something that may have been seen previously as an interesting experiment on the side is now core business, essential to the maintenance of any level of student experience. It’s worth reflecting for a moment on the fact that EdTech has reached a level of ubiquity that has largely enabled the continuation of learning for most students in this unprecedented crisis but also recognising monumental efforts of the academic and technology teams that have converted hours of teaching so rapidly.

However, speed can lead to tradeoffs in quality. There are clearly large differences in the provision of online learning to date. Jim referenced a recent survey that indicates student satisfaction with the online alternatives during lockdown can be as low as 33%. In contrast, FutureLearn’s average satisfaction currently stands at over 90%. As we move from “emergency response” to “the new normal”, the quality of the online offer provided by universities is going to become one of the defining factors of their success in the post-covid world.

Decision making and constant change

As Jim explained from the outset of his presentation, universities need to undergo a radical shift in their decision making processes to tackle the coronavirus problem. It’s not a ‘tame’ problem and universities won’t be able to solve it using their usual structures. It’s a ‘wicked’ problem, as complex as they come, and decision making will have to become a lot more agile to make decisions and take actions quickly – and change them if they aren’t working or the shape of the pandemic changes.

He also highlighted the need to be honest with ourselves and students and to avoid making false promises based on optimism alone. Otherwise UK higher education could walk the path of the ill-fated, now notorious Fyre Festival. This will likely mean negotiations with government about accountability and autonomy, where universities have freedom to define policy and where they must respond to policy.

How do we get to the new normal? Jim gives a clue to the principles that could be followed in his article here. We’re a long way from knowing what the ‘new normal’ is but based on this event, there are some watchwords that will help universities tread the path: safety, empathy, radical shifts in decision making and constant change. For some time to come, the new normal may be indefinable.