Selfies and Self-Portraits in China: The History

In this article, we’ll look at how individuals construct and perform their identity through images in China. Dr. Ting Guo starts off by considering the selfie culture in China, including the popularity of selfie-inspired beautifying apps. She will then discuss the history of self-portraits in China, and how this history intertwines with the change of social and political powers in Chinese society.

We will look at another popular form of representation in Chinese society: images of self. Like texts, images are important cultural products, and the production of images is also an interesting cultural practice. The popularity of smartphones with cameras and fast broadband connections in the twenty-first century has made our society increasingly digitised and visual, including our perception and representation of ourselves. From artistic self-portraits to playful selfies, images are used more and more by people around the world to interpret and present themselves.

Selfie

In 2013 the word, ‘selfie’ was selected by Oxford Dictionary as the Word of the Year, and is defined as ‘’a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and uploaded to a social media website”.

A selfie edited by touch-up applications

A selfie edited by touch-up applications

Like other places around the world, photographic self-portraits and selfies have become one of the most popular forms of content on Chinese social media. Selfie touch-up applications such as Meitu (美图, “beautiful picture”) and BeautyCam, have also become one of the basic apps in many Chinese people’s mobile phones, especially among young people. These photo-editing apps can improve one’s appearance in photos through smoothing the skin, enlarging eyes and slimming-down jawlines.

This craze for a perfect appearance in selfies in China has been seen by researchers such as Wen Hua, author of Buying Beauty: Cosmetic Surgery in China (2013), as a result of the thriving service industry in Chinese society which has a desire and preference for perfect appearance. Similar views on the selfie trend in China are also found in Western mainstream media. In an article entitled “China’s Selfie Obsession” in The New Yorker on 18 & 25 December 2017, Jiayang Fan points out that beautifying apps such as Meitu capitalise on people’s desire for success, and at the same time shape the Chinese public’s understanding of beauty and self-representation.

These negative views on the trend of selfies in China reinforce the prevailing image of ‘narcissistic’ and ‘snobbish’ selfie-obsessed people, overlooking the connections between the current selfie fashion and the social and cultural functions of self-portrait and photographs in Chinese society.

Self-portrait

Recent study on the culture of selfie, especially its connections with the history of self-portraits and the invention of photographic technologies provides a useful perspective for our understanding of the Chinese public’s craze for self-images. For example, Nicholas Mirzoeff, in his book How to See the World (2016), reviews the genre of self-portrait/ photographic self-portraits in visual art history.

Examining examples from the invisible but powerful king in the painting, Las Meninas (1656), by the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez, and the photographic fake in French photographer, Hippolyte Bayard’s Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (1839-40) to the male gaze at women in cinema in a series called Untitled Film Stills (1977-80) by the New York artist Cindy Sherman, Mirzoeff explores how self-portraits have been used by artists to shape our perception and understanding of power relationships embedded in every aspect of social life (e.g. class, gender, and race), and argues how today’s selfies enable ordinary people to take up the role of artists and perform their own identity (2016: 29-69).

This performance, according to Mirzoeff, should not be seen as a simple expression of selfishness and narcissism, because the significance of selfies lies in sharing them with others; therefore, it needs to be studied as an important part of communication and socialisation in our intensely visualised world (2016: 62-69). Mirzoeff’s observation of the shift from artists to the masses in cultural production and the representation of social reality in popular art also took place in Chinese history.

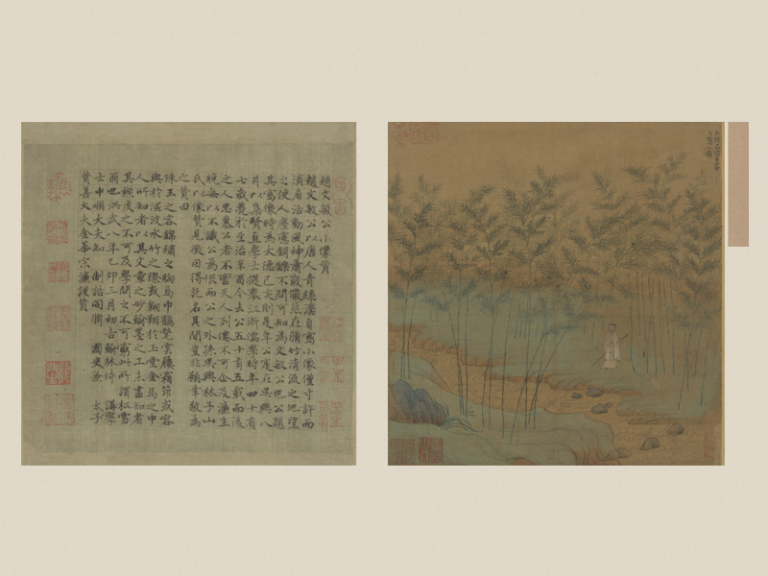

In traditional Chinese art, the self-portrait is never the mainstream, and has been heavily influenced by figure painting, in which the figure is situated in a specific setting to form a narrative. More importantly, traditional Chinese portraits emphasize less physical appearances but focus more on the spirit of the subject. A good example is Zhao Mengfu’s (1254-1322) Zi Xie Xiao Xiang (1299) (自写小像, a small self-portrait).

Zi Xie Xiao Xiang – A small self portrait

Zi Xie Xiao Xiang – A small self portrait

Rather than with a close up on the figure’s face like most portraits, Zhao portrays himself from a distance and in a bamboo forest. The figure of the artist himself is only 4cm in the 24 X 23 cm painting. Dressed as a middle-aged man in a white robe and white hat, he was standing in a bamboo forest, with a bamboo stick in his right hand. At the bottom of the painting, a stream runs across the forest, and the artist gazes over to the other side of the stream, at ease in the peaceful atmosphere.

Notably, the artist does not depict himself as the centre of attention, but the contrast formed between his white robe and green bamboo mark his presence. This presence is further defined by the surrounding bamboo and stream, both of which are enduring symbols of nobleness and virtuousness in Chinese art. Using and understanding the veiled meaning of these symbolic objects and scenery requires both literary and artistic training, which consequently limit both the producer and his/her audience to the elite group.

This is confirmed in the Commentary and Preface of Zhao’s self-portrait by Song Lian (1310-1381) (see the text on the left side of Zhao’s painting above).

In the Commentary, Song comments on Zhao’s use of colour and his refined taste portrayed in the portrait. While lamenting the fact that he was unable to meet Zhao in person, Song praises Zhao’s breadth of mind and his achievements in calligraphy and literature. This form of portrait commentary appeared in China as early as the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD), but became particularly prevalent during the Song Dynasty (962-1279). They can be comments on someone else’s portrait, or on the artist’s self-portrait. The popularity of self-portraits and portrait commentaries among Chinese literati and scholars indicates the secularisation of portrait culture in Chinese society on the one hand; on the other hand, it also suggests the social function and cultural meaning associated with self-portraits: practice one’s artistic taste and perform one’s cultural identity.

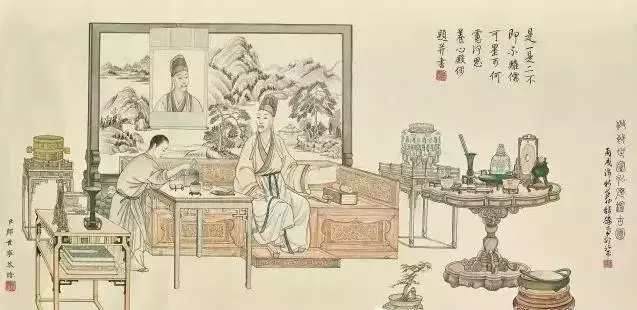

This specific cultural aspect of the self-portrait is exemplified in another interesting painting, Song Dai Ren Wu Tu (around 1082-1135), by an unknown painter.

Song Dai Ren Wu Tu by unknown painter [1]

Song Dai Ren Wu Tu by unknown painter [1]

This painting depicts a middle-aged man in a Confucian scholar’s robe and hat, sitting in a couch with a young boy waiting with drinks. The simply and elegantly decorated study, especially the presence of books, an incense burner, a seven-string Chinese zither, reveal the man’s elitist taste. What is more prominent in the painting, however, is the presence of his self-portrait hanging on a screen behind the man. Like a mirrored image, the portrait depicts the man in the painting from the opposite side, with the exact same clothes and facial expressions. The fact that it appears in such a space, typical of the Chinese literati, suggests the prevalence of self-portraits in Chinese elites’ cultural life in the Song dynasty. The similarities and contrasts between the man in the painting and his image in the self-portrait provide the viewers with a different perspective of the man; at the same time, it also reveals the literati’s emphasis on self-reflection and self-cultivation in their daily life. This painting was in the collections of several Chinese emperors, including Emperor Huizong of Song (1082-1135), Emperor Gaozong of Song (1107-1187) and Emperor Qianlong of Qing (1711-1799).

Emperor Qianlong even asked his royal painter, Ding Guanpeng (1708-1771), to reproduce a painting, titled Hongli Jian Gu Tu (Painting of Emperor Qianlong appreciating antiques), with a similar layout but replacing the figure in the painting with the emperor himself and the original decorations commonly seen in scholars’ study with various antiques collected by Qing court.

Scroll of Emperor Qianlong asking one or two

Scroll of Emperor Qianlong asking one or two

This painting is called Scroll of Emperor Qianlong asking one or two, because the Chinese text on the top right of the painting, written by the Emperor himself, raises an interesting philosophical question. This is similar to the question posed by Zhuangzi (c. 3rd century BCE), one of the founders of Taoism in his story, The Butterfly Dream[1a]: whether the figure painting hanging on the screen and the figure sitting in the arhat bed are in fact the same person?

This question highlights the metonymic reference of self-portraits and reveals the significance and history of self-portraits in Chinese culture, especially their use among the social elite. For members of this group, producing and appreciating self-portraits is a way to imagine, explore and question themselves as well as to perform their cultural taste and identity. This process was entangled with the tradition of self-cultivation in Confucianism and contested through Taoist relativistic scepticism.

Does this history affect the practice of photographic self-portraits in modern China? And how should we understand the popularity of selfies amongst the Chinese public?

Notes

[1a] This is one of the foundational texts in Taoism. In the story, Zhuang Zhou (Zhuangzi) fell asleep and in his dream he became a butterfly. However, when he woke up and remembered his dream, he could not tell whether he dreamed that he was butterfly or whether he was actually a butterfly, dreaming that he was a man. Through this story, Zhuangzi challenges the reality and existence (of human beings) and emphasizes the relativity of distinctions in the world.

References

- Song Dai Ren Wu Tu. Taiwan: Collection of National Palace Museum [Cited 10 October 2018]. Available from http://painting.npm.gov.tw/Painting_Page.aspx?dep=P&PaintingId=14553

Share this

Many Faces: Understanding the Complexities of Chinese Culture

Many Faces: Understanding the Complexities of Chinese Culture

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free