What Does Climate Adaptation Governance Look Like?

Share this step

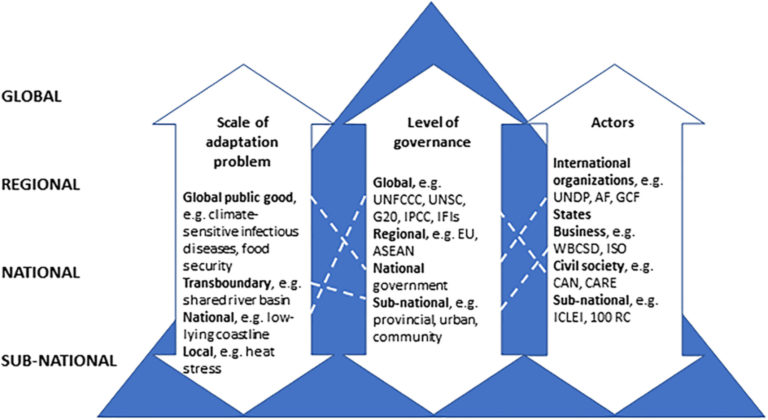

Climate adaptation governance involves different definitions of the problem (frames), different levels of governance (national, regional and global) and different actors (public, civil society, local administrators). This means climate adaptation governance is a complex process that requires in depth understanding and planning to achieve tangible results on the ground.

The connection between governance and climate adaptation is given by the following definition developed by Termeer et al., 2017:

Adaptation to climate change is not only a technical issue; above all, it is a matter of governance. Governance is more than government and includes the totality of interactions in which public as well as private actors participate, aiming to solve societal problems. Adaptation governance poses some specific, demanding challenges, such as:

- the context of institutional fragmentation, as climate change involves almost all policy domains and governance levels;

- the persistent uncertainties about the nature and scale of risks and proposed solutions;

- the need to make short-term policies based on long-term projections.

Three dimensions for conceptualizing global adaptation governance (Reference: Persson, Å. Global adaptation governance: An emerging but contested domain. WIREs Clim Change. 2019)

Three dimensions for conceptualizing global adaptation governance (Reference: Persson, Å. Global adaptation governance: An emerging but contested domain. WIREs Clim Change. 2019)Overview of developments

Sub-national climate adaptation governance

rules, process, and instruments that structure the interactions between public and/or private entities to realize collective goals for a specific domain or issue

Termeer et al., 2013; pg.161.

The climate adaptation decisions made at national levels and above, need to be implemented in the sub-national regions. National levels provide guidance through national adaptation policies and fiscal allocation. However, these policies are implemented in the subnational regional areas such as cities, districts and provinces. The lower levels have their own procedures for implementation of climate adaptation strategies. The procedures involve many actors and stakeholders such as councilors and other government officials, private actors, non-governmental organisations and the public.

Implementation

Implementation of adaptation policies in the sub-national region is difficult. The challenges faced can be grouped into three broad categories:

1. Context of divisions

The development and implementation of climate change policies and strategies involves different stakeholders and actors. These players may come from government, business, civil societies and the public. They might also come from different government sectors and national institutions. In a previous step we observed that climate change affects different sectors such as agriculture, health, energy supply, spatial planning and water management. Therefore, climate adaptation also involves these different sectors. The sectors are related to different policy systems and administrative levels. These have different formal and informal rules, many goals and finite resources. The complex environment of divisions within governance make formulation of climate adaptation policies difficult. For example, to address flooding in a city, you require attention to policies about urban spatial planning and water management. These policies belong to different administrative levels with different procedures and actors.

Due to these divisions, many stakeholders and actors, and different ways of working, the policy development for climate adaptation may encounter opposition. The opposition could take the form of bureaucracy or conflicts over responsibilities of the different sectors/actors. In the instance of climate adaptation policy, some approaches favour mono-centric governance systems to by-pass the divisions. However, mono-centric governance systems (also known as top-down or centralized) have disadvantages. They are less able to adapt and anticipate changes, and learning in this system is slow. The concept of polycentric systems (multi-level and multi-actor) allow for more flexibility, but we will discuss this later in the course.

2. Invention of new policy domain

The development of climate adaptation policy is a new domain. Due to this, it is characterized by weak policy frameworks, undefined goals, responsibilities and procedures. Climate adaptation governance may also address questions such as what problems should be addressed, who should address the problems and how should they address them. It is also relevant to think whether climate adaptation strategies should be temporary or be embedded in public policy.

These questions contribute to bureaucratic/political struggles about jurisdictions, procedures and budget allocations. What is clear is that specific adaptation policies are required to address the urgent need occasioned by climate change effects. Nevertheless, to include climate adaptation strategies in existing policy streams (‘mainstreaming’) is a challenge.

3. Inherent uncertainties in a knowledge-intensive domain

In order to develop appropriate climate adaptation approaches, policy-makers need reliable knowledge on the changing climate and future predictions. In a previous step we discussed controversies surrounding data and models of climate change. Despite these controversies, decisions about climate change adaptation need to be made. The uncertainties about the kind and scale of risk make it even more difficult for stakeholders and actors to agree and design adaptation solutions. Another big disadvantage is that data and models on climate change are usually collected on a global scale, making it difficult to translate them into sub-national levels, where policies need to be implemented. It also makes it hard to institute legitimacy to climate adaptation strategies already being implemented, if effects are not yet visible locally. This kind of policy development requires a combination of long-term adaptation goals with short-term urgent action.

Complexity

In conclusion, climate change presents complex governance problems including, having various stakeholders and actors, changing political agendas and budgetary limitations. These difficulties require concepts to guide development, testing and implementation of new governance arrangements. There are a variety of approaches developed by non-governmental organisations and meta-regional arrangements.

Further reading For more foundational reading on climate change adaptation we recommend the following chapter: Termeer C., Dewulf A., Breeman G. (2013) Governance of Wicked Climate Adaptation Problems. In: Knieling J., Leal Filho W. (eds) Climate Change Governance. Climate Change Management. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

References:

Emma Tompkins and Neil Adger, Defining Response Capacity to Enhance Climate Change Policy, 8 Env. Sci. Pol. 562 (2005).

Mike Hulme, Why We Disagree about Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity (2009).

M. Kok and H. C. de Coninck, Widening the Scope of Policies to Address Climate Change: Directions for Mainstreaming, 10 Env. Sci. Pol. 587 (2007).

Termeer C., Buuren v. A., Dewulf A., Huitema D., Mees H., Meijerink S., and Rijswick v. M. (2017) Governance Arrangements for Adaptation to Climate Change. Oxford Research Encyclopedia on Climate Science.

Share this

Making Climate Adaptation Happen: Governing Transformation Strategies for Climate Change

Making Climate Adaptation Happen: Governing Transformation Strategies for Climate Change

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free