This article is from the free online

The History of the Book in the Early Modern Period: 1450 to 1800

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Fig 1. Portrait of James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh, writing in a note-book: Richard Parr, The life of the Most Reverend Father in God, James Usher, late Lord Arch-Bishop of Armagh, primate and metropolitan of all Ireland (London, 1686), frontispiece. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 1. Portrait of James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh, writing in a note-book: Richard Parr, The life of the Most Reverend Father in God, James Usher, late Lord Arch-Bishop of Armagh, primate and metropolitan of all Ireland (London, 1686), frontispiece. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

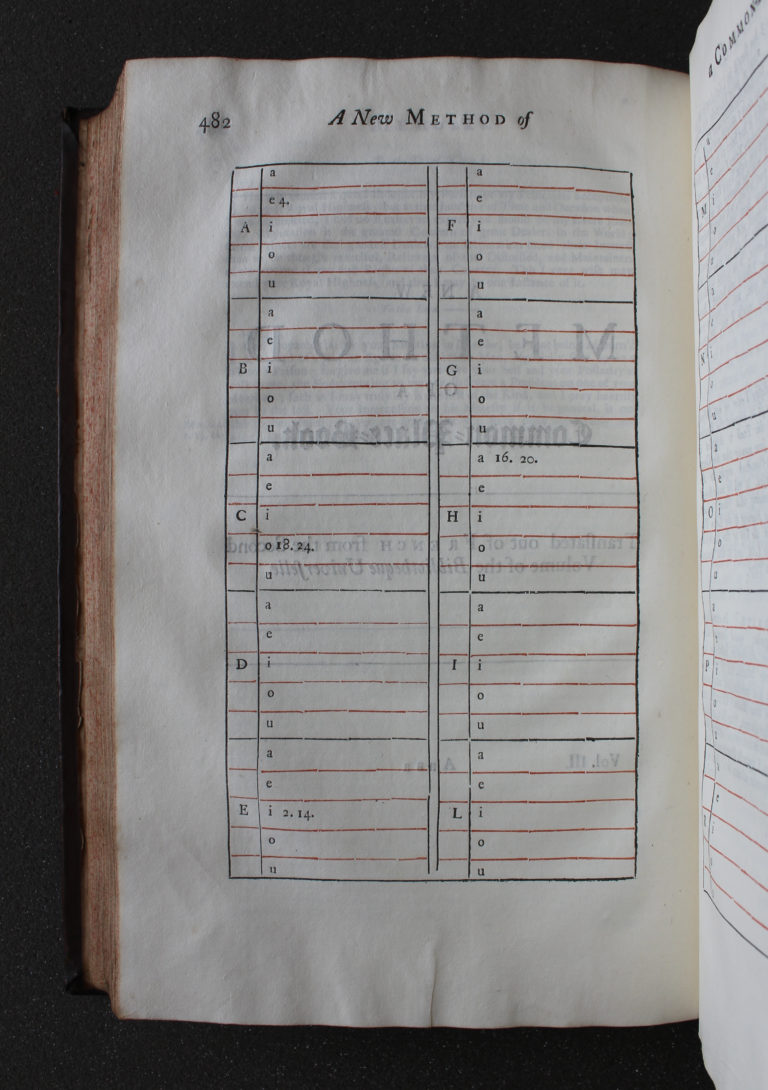

Fig 2. How to index a commonplace book in John Locke, The Works of John Locke (London, 1714), vol iii, p. 482. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 2. How to index a commonplace book in John Locke, The Works of John Locke (London, 1714), vol iii, p. 482. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

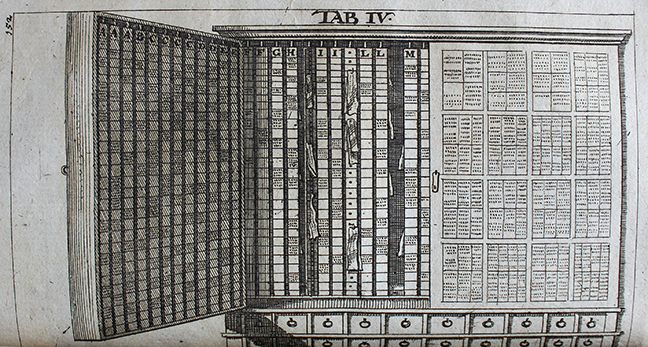

Fig 3. A note closet, in Vincent Placcius, De arte excerpendi (Stockholm and Hamburg, 1689), Tab IV. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 3. A note closet, in Vincent Placcius, De arte excerpendi (Stockholm and Hamburg, 1689), Tab IV. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

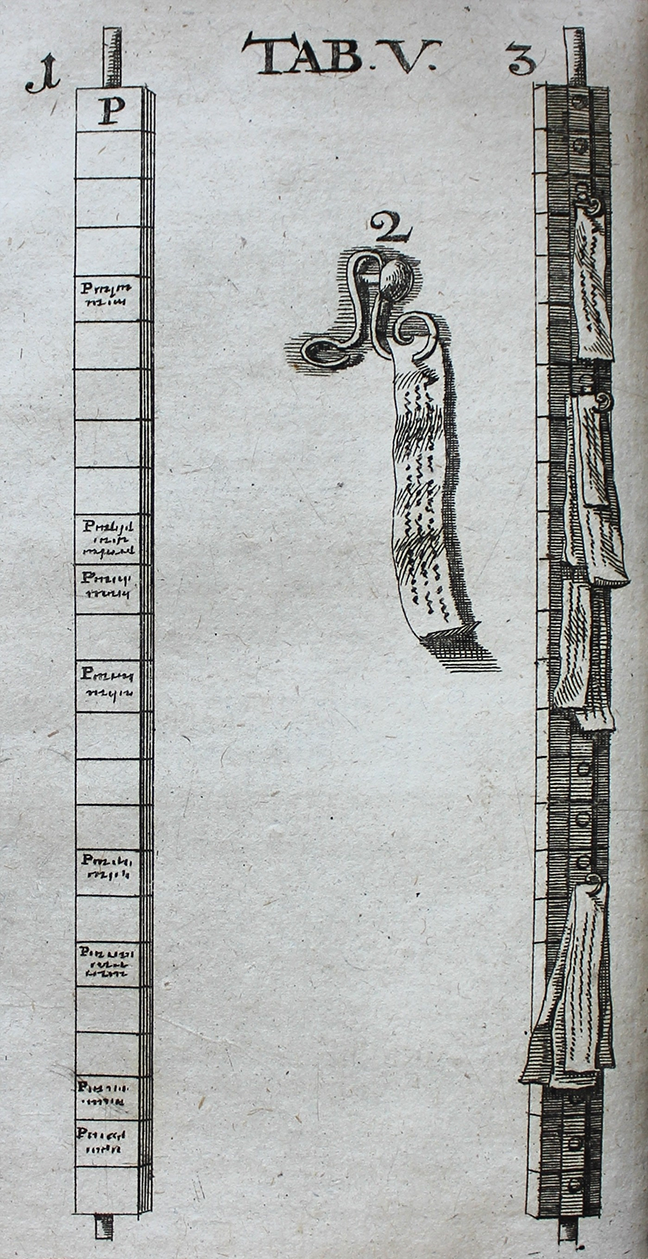

Fig 4. Slip of paper on hook, used in the note closet in Vincent Placcius, De arte excerpendi (Stockholm and Hamburg, 1689), Tab V. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Fig 4. Slip of paper on hook, used in the note closet in Vincent Placcius, De arte excerpendi (Stockholm and Hamburg, 1689), Tab V. © The Trustees of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.