How Micro Behaviours Lead to Macro Outcomes

Share this step

Sometimes it appears that a small spark can lead to a big social action, while in other cases it seems that everyone would want something to change (e.g. an unfriendly organisational culture) but people seem to be stuck and nothing happens.

Dynamics of demonstrations is a typical case here – we already know that it is hard to predict how many people will come to a demonstration. In the case of Fruit County protests we can observe that similar levels of discontent could produce a small or a big protest, depending on the presence or absence of initiators, the size of the early-goers group or discrepancies between thresholds.

Getting back to real protests – what we can also observe is that sometimes when people do turn up and just march through the city with their banners, a seemingly small incident can change a peaceful march into a riot. In other words, sometimes we cannot see the potential of a collective action and it is revealed only when some people initiate the action. Or despite the fact that there is some potential for such action, it doesn’t lead to anything. This might be puzzling but it’s just one of the examples of social mechanisms that lead from individual attitudes or ideas, or desires to the final result that we can observe in a group.

In such phenomena we can see two ‘levels’: the individual level of separate people (the micro level) and the group level where we can see the combined effect (the macro level). The problem of connecting those two levels is called the micro-macro problem.

In some of our other articles, we explore a model of a social process – we analyse how a protest comes to life, step by step, starting with a simple observation that for each protest to occur, individual people have to make a decision that they want to join it. In this model we also assume that people are more willing to go provided that some people are protesting. We use the term threshold to describe a minimum number of protesters needed for a certain person to join the protest. (It’s worth mentioning that this simple model is an example of a wider array of threshold models proposed and investigated by a sociologist Mark Granovetter in the 1970s.) Although the model itself is pretty simple, the results are not so obvious. It helps us understand how some collective actions develop.

So, let’s describe it step by step. In the case of a demonstration we explored a very simple social process: people (on the micro level) were more or less eager to go to a protest (which was represented by their thresholds) and they made their decisions based on observation of each other’s behaviour. However, the result on social (macro) level wasn’t just a simple sum of independent behaviours of individuals. People influenced each other, initiators played a really important role in the process while discrepancies made it difficult for the number of protesters to grow. So, a lot happened between the micro and the macro level!

Protestor by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona via Unsplash.

Although it was a simple example, it helped us illuminate some pretty important issues related to collective actions, for example the importance of the initiators and the size of the early-goers group for the growth of the protest. This example shows how – in order to understand social behaviour – we need to pay attention not only to the individuals but also to what is between them – for example to the way they influence each other.

There are a lot of other processes that lead from individual behaviours (micro) to a social effect (macro):

For example, if we have a number of individuals that produce a certain commodity and a number of potential buyers, what connects them all is some sort of market. And in order to find out how the producers and customers end up – do they succeed in selling or purchasing a good and what price they settle on, we need to study the characteristics of the market. In the well-known story of the invisible hand of the market (which is now perceived with much more caution than before), eventually they are all happy with the final result. Market is an example of a mechanism that connects individual behaviours and their result on a macro level.

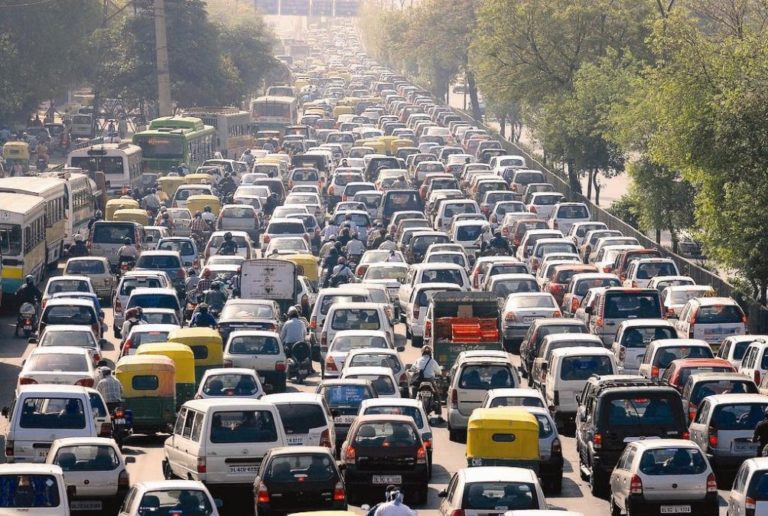

Another example: sometimes our individual behaviours, which seem understandable and don’t seem harmful at all on an individual level, like a simple decision of driving a car to work, lead to traffic jams which is far from satisfying for all the commuters and city-dwellers.

Image: Traffic jams are not created on purpose, but are an effect of thousands of decisions, each of those decisions harmless, but taken together, rather problematic, both for the drivers and other city-dwellers.

Image: Traffic jams are not created on purpose, but are an effect of thousands of decisions, each of those decisions harmless, but taken together, rather problematic, both for the drivers and other city-dwellers.

The way how thousands or millions of individual decisions can affect the whole society is often unintuitive and unexpected. People want to buy certain products before the others do and their behaviour – taken together – leads to a shortage that wouldn’t have occurred if they didn’t fear this shortage. On the other hand, if many people fear that a local event will be too crowded, they won’t come which actually prevents the fulfillment of their expectations.

Image: Self-fulfilling prophecy – people who were stockpiling toilet paper because they feared the shortage of this product, caused the shortage themselves.

Image: Self-fulfilling prophecy – people who were stockpiling toilet paper because they feared the shortage of this product, caused the shortage themselves.

There are a lot of different mechanisms that lead from individual ideas, needs and attitudes to the combined effect. And what is important, just as in case of the story of Fruit County villages there are many unexpected things that can happen on the way. Egoistic motivations can lead to a positive result, good intentions can lead to creating problems, we can observe self-fulfilling prophecies or self-cancelling prophecies. When we are dealing with social behaviour we should pay attention not only to what people think but also how they are connected, how they communicate, how they influence each other, what they expect from each other etc.

And if you are interested in exploring in more detail how seemingly rational choices can lead to problems, try out our Are we doomed to destroy our planet? course on Futurelearn (coming soon).

Additional Reading

A much more advanced approach to threshold models: check out Threshold Models of Collective Behavior. American Journal of Sociology, written by Mark Granovetter in 1978.

Share this

People, Networks and Neighbours: Understanding Social Dynamics

People, Networks and Neighbours: Understanding Social Dynamics

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free