Popular recognition and memorialisation

Share this step

Although Wellington’s reputation was forever linked to Waterloo, his victories in the Peninsular War had already made him a household name. From 1810 onwards his likeness began to appear on a range of merchandise, such as clocks, tea services, door stops and snuff-boxes.

This commodification took on a new phase with 1815. The naming of many items was opportunistic, a way of selling goods. At his death in 1852, personal items — quasi-relics, such as letters and locks of hair — were added to the mix. The Duke’s image was an icon that all would have recognised: paintings and drawings were engraved and circulated widely; and some 5% of the caricatures now in the British Museum’s collection depict Wellington.

Monuments to Waterloo and Wellington

Popular recognition, however, was taken a stage further by memorialisation. There were monuments erected across the country to the Duke and Waterloo, from the Scottish Waterloo Monument, at Ancrum, in the Borders, a tower of 150 feet built in 1817–23; the Wellington Testimonial Monument in Phoenix Park, Dublin, which took from 1817 to 1861 to construct; to the massive obelisk near Wellington in Somerset, started in 1817, but only completed in 1854 when additional funds had been raised after the Duke’s death. This renewed interest in memorials after the Duke’s death was typical of a wider pattern: Wellington’s Column, or Waterloo Memorial, in Liverpool, for example, was started in 1854 and completed in 1865. British memorials were overwhelmingly the result of public subscription, and this led to a stop–start quality in the construction of many — a contrast to the much larger schemes of public support for monumental work on the Continent. We should not therefore see the monuments in Britain as a state-inspired programme, but as broad movement in which individuals expressed the long-lasting importance of the commitment to the war against the French.

A national pantheon for British heroes

There was, however, one major exception to state support for monumental works. In 1795, Parliament had voted funds to support memorials to the British heroes of the Glorious First of June [1794], the battle in which the Royal Navy had defeated the French fleet in the Atlantic. The intention was that these monuments should be sited in St Paul’s Cathedral, to create a national pantheon in the centre of the capital. More than £110,000 had been spent on these sculptural monuments by 1850, but the scheme was less successful from an artistic point of view. It had established a tradition, however, that St Paul’s should be a burial site for heroes — that Wellington was buried there was a carefully considered decision.

Popular memorialisation

The Duke’s name and that of Waterloo were more widely used in less formal settings: in streets, buildings and public places, attached to works that were going on for other purposes, or simply as renamings as an act of homage. In London, by 1823, there were 14 places named after Wellington and 10 sites named after Waterloo. When the first portion of what then was called New Street (now Regent Street) was built in 1815–16, it was called Waterloo Place. One of the new bridges built over the Thames in 1813–19 became Waterloo Bridge.

The naming of public houses and inns after Wellington and Waterloo became widespread. In 1816, on the banks of the Mersey, near Liverpool, the Crosby Seabank Hotel was renamed the Royal Waterloo Hotel — and the village there gradually came to be called ‘Waterloo’. Through the Victorian period it acquired streets, villas and cottages named after those who had taken part in the battle — from Wellington Street and Anglesey Terrace to Picton Road, Blucher Street, Brunswick Mews and Murat Street; there was also a Hougoumont Avenue.

Some of the naming made a direct connection to the Duke’s military career. Regiments in armies were named after the Duke: the 33rd Regiment of Foot in the British army, of which he had been colonel, was renamed the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment in 1852. Wellington College in Berkshire, which opened in 1859, was built in memory of the Duke, and originally provided for the children of officers who had lost their lives in the service of the country.

The spirit of the age

If there was a common sense of the significance of Waterloo and that those who had taken part in the battle were due special recognition, this, by itself does not entirely account for the phenomenon. There was something else, a spirit of the age, well captured by Thomas Carlyle. His work, Heroes, hero worship and the heroic in history, published in 1840, put at the centre of the past the lives of great men — and Wellington was the greatest of them all: it was they who constituted the history of the world. At the same time, the public funding for the memorials in St Paul’s had intended that these works should provide moral improvement for the people who saw them — commemorating the fallen might inspire others to similar deeds. There were increasing numbers of memorials through the 1830s and 1840s, as old heroes came to the end of their days — and the death of Wellington gave this movement special impetus. Memorials across the nation demonstrated the contribution that all the heroes, be they English, Welsh, Scottish or Irish, had made to the country’s history.

Activity

You have already been on the look out for places and memorials linked to Wellington and Waterloo. Have you also found objects and memorabilia? Would you like to share examples of those you have encountered? When were they made, where and for whom? How much might they have cost?

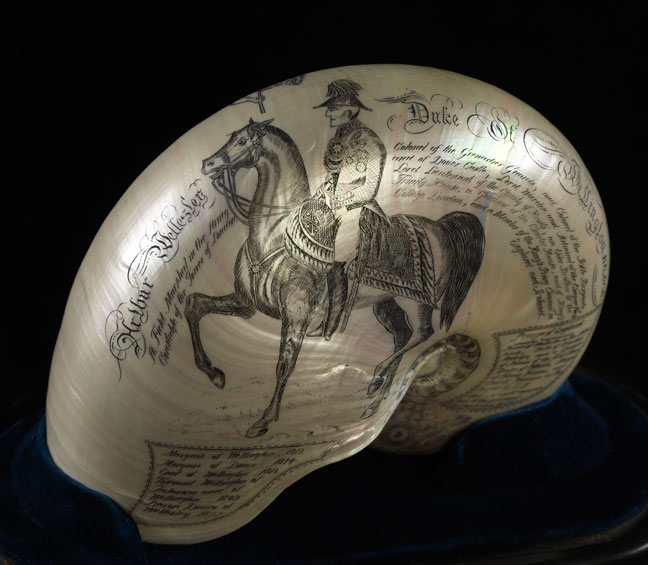

Document: Scrimshaw nautilus shell, engraved by C. H. Wood.

© University of Southampton Library, MS 351/6/28.

© University of Southampton Library, MS 351/6/28.

Produced in the 1850s, this engraved shell promotes the idea of Wellington as a great English national hero, depicting the Duke on one side and St George slaying a dragon on the other. Wood engraved other nautilus shells in the 1850s: one to commemorate Nelson’s victories, again with St George on one side, is in the National Maritime Museum; there are two examples engraved with Britannia, c.1855, one now in Gallery Oldham — the other was given to Queen Victoria.

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free