Leading in a Crisis: Organizational Stakeholders

Organizations exist because of their ability to create valued goods and services that provide acceptable outcomes for a collection of stakeholders. These stakeholders, simply put, are groups of people who have an interest, claim, or stake in the organization, in what it does, and in how well it performs. Business is ultimately about the creation of value through the interactions between and among these stakeholders. To understand a business is to know how these relationships work. An executive’s or entrepreneur’s primary function is to create, manage, and shape these relationships and the value propositions that result from them.

Stakeholders are motivated to engage with an organization if they receive benefits that equal or exceed the value of the contributions they are required to make in exchange for them. These benefits can be thought of as rewards such as goods, services, money, power, satisfaction from association, the support of shared beliefs or values, or organizational status. Contributions can be thought of as money, goods, services, opportunities, time, effort, loyalty, or the skills, knowledge, and expertise that organizations require of their members during task performance. We will not conduct a deep exploration of all potential methods of value exchange between stakeholders in this course – we simply don’t have the time. To truly understand the relationships between stakeholders and an enterprise, however, high stakes leaders must have a good sense of the range of potential sources of value that are available for exchange. Why? Because during a crisis, it is precisely these benefits and contributions – informed by the extent to which some part of a value exchange has already commenced – that become threatened. Understanding stakeholders means understanding their perceptions of the contributions they have made or are making in exchange for the benefits they expect to receive. In other words, understanding stakeholders means understanding their perceptions of the value proposition they have or could have with an organization.

Stakeholder value propositions would be sufficiently challenging to calculate if they were simply economic formulae (e.g., Value = Tangible Benefit – Cost). Unfortunately, a fundamental premise of this course is that organizational stakeholders are not simply emotionless automatons who perform their value proposition calculations using only the material components of an exchange. Rather, stakeholders will ALWAYS include their humanness – their aspirations, expectations, and emotions – in their calculus. Consider, for a moment, the last time you made a purchase that didn’t meet your expectations. Did you simply recalculate the value of the exchange in the context of the reduced benefit you actually received? Or was your reaction to this scenario as much emotional as it was economic? There was almost certainly an element of emotion in your reaction – perhaps a sense of disappointment, or sadness, or frustration, or anger. This is simply an element of the human condition. When someone or something doesn’t meet our expectations, we have feelings about it. In the context of crisis leadership, this human element will be a primary area of focus for high stakes leaders. To engage stakeholders in the most effective ways possible, before, during, and after any crisis event, leaders must be able to recognize and respond to the psychological implications of a crisis as much as the material.

This idea of stakeholders and the relevance of their humanness is not new. In his book Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art, researcher Ed Freeman describes a business’s relationships with stakeholders this way:

“To create value for stakeholders, executives and entrepreneurs must see business as fully situated in the realm of humanity. Businesses are human institutions populated by real live complex human beings. Stakeholders have names and faces and children. They are not mere placeholders for social roles. Most human beings are complicated. Most of us do what we do because we are self-interested and interested in others. Business works in part because of our urge to create things with others and for others. Working on a team, or creating a new product or delivery mechanism that makes customers’ lives better or happier or more pleasurable all can be contributing factors to why we go to work each day. And, this is not to deny the economic incentive of getting a pay check. The assumption of narrow self-interest is extremely limiting, and can be self-reinforcing — people can begin to act in a narrow self-interested way if they believe that is what is expected of them, as some of the scandals have shown. We need to be open to a more complex psychology — one any parent finds familiar as they have shepherded the growth and development of their children.”

What is the key lesson here? That we have relationships with our stakeholders not simply to extract economic value, but to make their lives better – to make the execution of their responsibilities more meaningful, satisfying, and enjoyable. And when value propositions are threatened during a crisis, there isn’t simply a material impact, there is a personal impact as well. Interestingly, the Ross School of Business is known for its Center for Positive Organizations, an academic unit dedicated to business that enriches the lives of its stakeholders. If you’re interested in learning more about them, you can find information at this link.

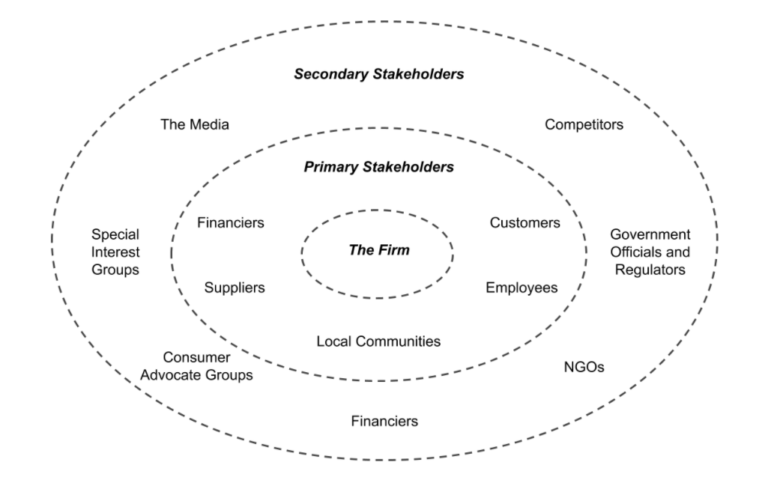

Who are your stakeholders? The following provides an introduction to the collection of typical organizational stakeholders and their value propositions. Figure 1 graphically illustrates this collection.

Figure 1: Typical Enterprise Stakeholders

Starting with the organization or firm in the center of the graphic, you will notice two rings of stakeholders. The inner ring, labeled as Primary Stakeholders, are relevant to just about every organization, regardless of industry or state of maturity. These are also the stakeholders who will be most significantly impacted by an organizational crisis. The outer ring, labeled as Secondary Stakeholders, may or may not have a relationship with a given organization. Over time, most organizations will have some degree of interaction with all of these.

If this generic approach to differentiating primary and secondary stakeholders doesn’t feel particularly satisfying, you may prefer to conduct the following mental exercise to determine the primary stakeholders at your organization. In an HBR article titled Five Questions to Identify Key Stakeholders, author Graham Kenny offers these five questions to help you “direct your organization’s energy and resources to the right relationships.” If your responses match those required below when considering a particular stakeholder, then they deserve your attention as a primary stakeholder.

1) Does the stakeholder have a fundamental impact on your organization’s performance? (Required response: yes.)

2) Can you clearly identify what you want from the stakeholder? (Required response: yes.)

3) Is the relationship dynamic — that is, do you want it to grow? (Required response: yes.)

4) Can you exist without or easily replace the stakeholder? (Required response: no.)

5) Has the stakeholder already been identified through another relationship? (Required response: no.)

Typical Primary Stakeholders. Here is a list of typical primary stakeholders and a very brief description of their value proposition with an organization.

Enterprise Leadership. This group has a unique set of responsibilities and, in exchange for their leadership, they extract a great deal of value from the enterprise. As stated earlier, these leaders are expected to create, manage, and shape relationships with all other stakeholders. When the organization is performing as expected, these leaders tend to receive the credit. When the organization is not performing, they tend to be held responsible. Also, because stakeholder interests typically conflict (e.g., employees want high pay while investors want low costs and high margins), enterprise leadership must find ways to resolve these conflicts in the best ways possible.

Employees. Employees are the primary internal stakeholder of an organization (larger in scale, cost, and complexity than Enterprise Leadership). These stakeholders often have a desirable set of specialized skills, a value system similar to the organization, and are willing to provide time, energy, and a commitment to an enterprise. In return for their labor, employees expect security, wages, benefits, and meaningful work. Most employees also expect an opportunity to grow and increase their value proposition over time within the organization.

Customers. Customers and suppliers exchange resources for the products and services of the firm and in return receive the benefits of those products and services. These stakeholders will be expecting value in exchange for something of value that will be or may have already been exchanged for it, such as the items mentioned earlier (e.g., money, goods, services, opportunities, time, effort, loyalty, etc.).

Investors. Owners or financiers have a financial stake in the business in the form of stocks, bonds, and other currencies. They expect some kind of financial return from their investments. Financiers typically expect these returns in a specific time frame (e.g., short-, medium-, or long-term) and are typically doing so at a predictable and predetermined level of risk.

Regulators. Governmental officials typically play one of two different roles in their relationships with an organization. While all regulatory officials are elected or appointed to serve the interests of their constituents, some are expected to look after the interests of the communities they serve (e.g., mayors, governors, etc.), while others are expected to oversee enterprise compliance (e.g., safety or legal officials). The value propositions of all regulators can be found in the organization’s ability to perform as it is expected to perform. When an enterprise serves a community well, community leaders will tend to highly value it. When an enterprise complies with regulations and meets or exceeds regulatory standards, officials responsible for compliance will be satisfied.

Media. The media can be a primary stakeholder for an organization, especially in today’s social media-heavy environment. While the value proposition of the media group is quite different than the groups previously mentioned, members of the media will look to an organization for stories that serve the interests of their audiences. The more interesting the stories, the greater the value proposition for the media. Also, when stories of great interest can be reported exclusively by a single outlet, this increases the value proposition for the specific outlet significantly.

Competitors. Why might competitors be viewed as a typical stakeholder for an organization? Not surprisingly, there are many ways an organization can behave that impact the decision-making and performance of its competitors. Most people understand the fundamentals of competition and competitive forces undoubtedly influence all companies in a given industry. What is not so clear to most, however, is the extent to which an organization can influence the way its stakeholders view other competitors in that industry. Because of this potential to influence different groups with both strategic and tactical organizational choices, high stakes leaders should think of competitors as primary stakeholders that can be significantly influenced by its performance.

As a high stakes leader, you will need to find ways to effectively manage, mitigate, and recover from these threats and, along the way, purposefully engage your stakeholders – not as instruments of economic value, but as members of your organizational family.

Share this

High Stakes Leadership: Leading in Times of Crisis

High Stakes Leadership: Leading in Times of Crisis

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free