The Abdication of Napoleon

Share this step

This article considers the remarkable conclusion to Napoleon’s great empire with his unconditional abdication as Emperor of the French on 6 April 1814, at Fontainebleau. This marked an end to over two decades of warfare and to the empire that Napoleon had fashioned for France.

To the last Napoleon had remained unyielding, collecting troops at Fontainebleau with the intention of continuing the military campaign, even though Paris had surrendered to the allied powers on 31 March. On 4 April Napoleon met with his military commanders — Marshals Ney, Lefebvre, Moncey, Oudinot and Macdonald — who urged him to abdicate as, they stated, he no longer had the support of the army. Faced with this loss of support, Napoleon now contemplated the prospect of abdication. He initially offered to abdicate in favour of his son, but the defection of Marshal Marmont and his forces on the 5 April undermined his position further and led to his unconditional abdication the following day.

How had this situation come about?

It was not the case that the deposition of Napoleon, rather than the defeat of the French, had always been an aim of the allies. It was not agreed as one of their war aims until late 1813. Throughout 1813, as the military campaign had begun to turn in favour of the allies, they continued to make overtures for peace with France and a ceasefire was agreed by the armistice of Pleiswitz, signed on 5 June 1813. These peace efforts culminated in February and March 1814 in a peace conference held at Châtillon, at which Caulaincourt, the Foreign Minister, attended on behalf of the French government. The talks were ultimately to prove fruitless, as Napoleon rejected the peace terms offered, and it was in the wake of Napoleon’s uncompromising stance that the British government, represented by Lord Castlereagh, was able to unite the allies in their war aims. By the Treaty of Chaumont (9 March 1814) they formalised an agreement to fight against Napoleon until their common war aim was achieved.

The catastrophic Russian campaign of 1812 marked a turning point for Napoleon and French expansion, even if it did not destroy the spell cast by Napoleon’s previous victories or his status as a formidable commander. His exhausted and depleted forces were unable to achieve a decisive victory against the allies at the Battle of Bautzen (20–1 May 1813) and the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813 was a catastrophe probably second only to the Russian campaign of 1812: it effectively marked the end of the French empire east of the Rhine. The considerable losses of men — a loss that could not be easily replaced — and disillusionment created by the defeat not only debilitated the forces, but led to discord at home. Efforts to raise finances to continue funding the campaign and to replenish the ranks of the army in the wake of this defeat contributed to unrest in France. Napoleon was to enjoy some military successes in the so-called ‘six-day campaign’ of February 1814, which persuaded him to reject the peace overtures from the allies, but he was not able to exploit these military advantages and was defeated at the Battle of Laon (9–10 March) and at Arcis-sur-Aube (20–1 March). Moreover, at the same time that Napoleon was occupied on one front, the Duke of Wellington and his troops had entered southern France and were attacking on another front in order to make their way north towards Paris.

Why was political support for Napoleon diminished?

Politically, Napoleon no longer enjoyed significant support in France outside the army and with continued defeats enthusiasm even within the army for the military campaign was dwindling. The ongoing war led to higher taxes and fresh conscription to fill the ranks, causing unrest and resistance across the country and a revolt in Hazebrouck, in the Département du Nord, in November 1813. Napoleon lost support in Paris in late 1813 by refusing to conciliate with the notables and by dissolving the country’s legislative body when it urged him to consider peace terms. With Napoleon’s final rejection of peace overtures in early 1814, Paris, and in particular Prince Talleyrand, the French foreign minister, began making overtures to the allies. The declaration on 12 March by Bordeaux, the fourth largest French city, in favour of the restoration of the Bourbons to rule France was a significant blow to Napoleon’s cause and was followed by the collapse of resistance and the capture of many other important cities by the allies.

What did the allies decide to do with Napoleon?

Following the abdication of Napoleon, the allies were faced with the question of what to do with the former Emperor. Their conclusion was that he needed to be deposed and sent into exile. They feared that any attempt to overthrow him would risk civil war and as the British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, noted ‘any peace with Buonaparte will only be a state of preparation for renewed hostilities’. The conditions covering Napoleon’s abdication were set out by the Treaty of Fontainebleau, signed by the allies on 11 April 1814. In return for his abdication as Emperor of the French, Napoleon was granted the title of Emperor, given the sovereignty of the island of Elba, off the coast of Italy, and granted an annual pension of 2 million francs from the French government. Thus the years of the French Empire under the rule of Napoleon were brought to an end and the work of the allies in how to shape France in the post-empire period was about to begin.

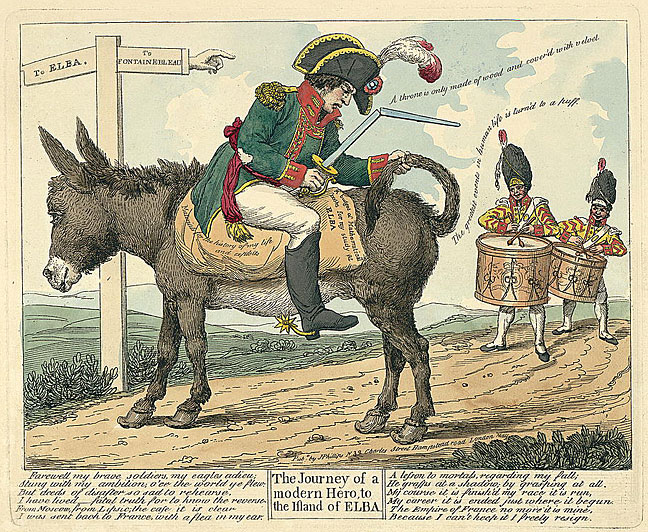

Document: The journey of a modern hero, to the island of Elba

There was a popular market for satirical cartoons in Great Britain. Napoleon had frequently been caricatured as a small man (as in the ‘Plumb-pudding in danger’) — and making him the object of ridicule became a significant element in sustaining popular morale in the long period of the wars. His exile to Elba was therefore an obvious target for satirists. This cartoon, ‘The journey of a modern hero, to the island of Elba’, by J. Phillips, was published in May 1814, and shows the disgraced emperor riding backwards on a donkey, a typical pose of humiliation, with his sword broken. The poem makes much of the immorality and consequences of his ambition.

Napoleon: A throne is only made of wood and cover’d with velvet

Donkey: The greatest events in human life is turn’d to a puff

Saddlebags: Materials for the history of my life and exploits. A bagful of Mathematical books for my study on ELBA.

The Journey of a modern Hero, to the Island of ELBA

Farewell my brave soldiers, my eagles adieu;

Stung with my ambition, o’er the world ye flew;

But deeds of disaster so sad to rehearse,

I have lived — fatal truth for to know the reverse.

From Moscow. from Lipsic; the case it is clear

I was sent back to France with a flea in my ear.

A lesson to mortals, regarding my fall;

He grasps at a shadow; by grasping at all.

My course it is finish’d my race it is run,

My career it is ended just where it begun.

The Empire of France no more it is mine,

Because I can’t keep it I freely resign.

Document: Letter from Lord Liverpool, the British Prime Minister, to the Duke of Wellington, 24 March 1814

In the extended reading below, Lord Liverpool set out for Wellington no more than a fortnight before Napoleon’s abdication the uncertainties involved in keeping the international coalition against him together. The British Foreign Secretary, Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, had been keen to ensure that the allies were united in their war aims and achieved this in the treaty of Chaumont signed on 9 March. This treaty committed the allies to continue the war against France and Britain pledged a £5 million subsidy to be divided amongst the allies. The British government viewed the royalist cause and the restoration of the House of Bourbon as the best means of governing France once the war was ended. This letter from Lord Liverpool describes how far the British government was prepared to go in support of its aim.

Fife House, 24 March 1814

My Dear Lord

I am much obliged to you for your letter, which I received a few days ago by Major Fremantle. We have since received your letters of the 14th, with the important intelligence of the occupation of Bordeaux by a division of your army under Marshal Beresford, and of the declaration of the civil authorities and people of that city in favour of the House of Bourbon.

I shall direct a copy of the instructions which have been sent in consequence to Lord Castlereagh to be forwarded to you.

The case which has arisen has been foreseen from the beginning as possible; and, as far as was practicable, provision has been made for it.

At a meeting of the ministers of the Allied Sovereigns at Langrès, on the 29th of January, when they settled the principles on which they were ready to negotiate with Buonaparte, Lord Castlereagh declared that though he was ready to negotiate and conclude peace with Buonaparte on the part of his government, as the sovereign de facto of France, yet if anything should occur in the course of the negotiations to call his power in question, he reserved to himself the right of suspending the negotiations, or of adopting such course as, according to circumstances, might then be expedient.

That the declaration of the second or third city in France, as Bordeaux maybe said to be, in favour of the Bourbons, combined with the account you have given us of a similar sentiment pervading the adjoining country, does in a degree call Buonaparte’s power in question cannot be denied. The question is altogether one of degree. Every effort of this nature must have a beginning: a more promising one could not have been expected; and it remains to be seen to what extent it spreads.

Whilst we are determined, however, under present circumstances to keep off the conclusion of any treaty of peace with Buonaparte, we must endeavour to manage our Allies. Our decision may at first alarm them. I entertain confident expectations that they will be reconciled to it if the preliminaries shall not actually have been signed before they receive the communications of yesterday. If the preliminaries shall have been signed upon our own terms, the business will be more difficult; and their decision will very probably then depend upon the degree in which the spirit which has manifested itself at Bordeaux extends itself. At all events, much will be done by gaining time; and I am sure you will see the importance of furnishing us with the most early information on the following points. First, on the progress of the royalist spirit throughout the south and other parts of France within your observation or cognizance. Secondly, the resources which the country can afford for the support and furtherance of that cause. Thirdly, what would be the prospect of ultimate success if the other Allied Powers were to withdraw from the contest, either by making a separate peace, or by retiring with their armies to the frontier, and Great Britain should be left to carry it on unsupported by any power except the nations of the Peninsula and the royalists themselves. The last alternative is one which must be most seriously considered.

If the Austrians were determined either on withdrawing from the interior of France, or on making their separate peace, the Russians and Prussians would never attempt to preserve their present station; and we should then have to decide whether we would make peace jointly with the Allies, or continue the war in France, under such circumstances, in support of the royalist cause.

I have not the least apprehension of the Emperor of Austria being actuated by any tenderness towards Buonaparte on account of the connexion with his daughter. I can even say that in my judgment he has been disposed to act more fairly about the Bourbons than either of the other great military powers. But the Austrians of all descriptions, military and political, dread the power of France; and with resources far more considerable, and a better organized military system, than either Russia or Prussia, they want the spirit of enterprise and self-confidence which belong in a very considerable degree to both the other powers.

We shall wait with the most anxious solicitude for the next intelligence from you; and we must only now hope (as so considerable a portion of territory and population has already committed itself against Buonaparte) that the flame will extend itself so widely as to leave no doubt of the insufficiency of Buonaparte to answer for the French nation.

I have thus communicated to you freely my sentiments on the present most singular and important crisis. I have no apprehension of any difficulties in Parliament at present, whatever may exist hereafter, if the line of policy adopted by the government should prove unsuccessful.

[From A.R. Wellesley, second Duke of Wellington, ed., Supplementary despatches and memoranda of Field Marshal Arthur Duke of Wellington, KG (15 vols., London, 1858–72) [abbreviated hereafter to SD], viii, pp. 680-2]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free