Battle of Waterloo: Armies, Battle Tactics and Orders

Share this step

The three armies at Waterloo — the French under the overall command of Napoleon, the Anglo-Allied forces commanded by Wellington, and the Prussian forces commanded by Field Marshal Blücher — were broadly organised along similar lines.

Corps and divisions

The largest independent military unit was the corps: at Waterloo Wellington had three infantry and one cavalry corps, Napoleon four infantry and two cavalry corps, and Blücher eventually brought one whole infantry corps and parts of two others onto the field. These corps were composed of divisions (usually two or more brigades), brigades, regiments and battalions, although the Prussian army used large brigades rather than divisions. Normally corps were commanded by generals or lieutenant generals within the British army and by a général de division in the French; the divisions were led by major generals, brigades by brigadier generals and regiments and battalions by lieutenant colonels or majors. There were some differences at Waterloo, with the divisions in the British army commanded by lieutenant generals. In the eighteenth century, it was understood that a division would have forces of all arms — infantry, cavalry, artillery; the French, however, concentrate either infantry or cavalry in their divisions, linking them up into larger corps d’armée.

Regiments and battalions

The basic unit in these armies was the regiment. In the British army, regiments were led by a colonel. The regiment varied in size — a consequence of the way the army had been expanded in the early 1800s — but with two battalions, and officers, on active service it might total some 2,250 men. The first battalion, the stronger of the two, was composed of about 1,000 men, made up of 10 companies of 100; the second battalion might only put in the field about 700 men (as the less able soldiers, those deemed ineffective for various reasons, would have been transferred to it from the first battalion). Warfare depleted the ranks and regiments took time to return to full strength.

Chains of command

The chain of command stretched from the commander in chief of the army to the general in the field, and down to his non-commissioned officers in the field. Staff officers were link across this chain, the channel of communication by which a commander controlled and commanded his army. Staff officers of the French army were more numerous at Waterloo, partly because Napoleon needed to keep in touch with not only the Armée du Nord but also with other armies on the frontier and with the government in Paris. The French army, like that of the Prussians, had staff officers at every regimental headquarters. The staff around Wellington usually numbered 40 or more, although his personal staff consisted only of his military secretary, Lord Fitzroy Somerset, and his aides-de-camp.

Communications between commanders

Wellington and Blücher had met in Brussels in May when they had discussed a strategy for the campaign and agreed the disposition of their respective forces. To facilitate communication between the two armies, liaison officers were placed at their headquarters and the communication links across the forces were carefully maintained.

Wellington and Napoleon as commanders

Unlike Napoleon who was prepared to delegate to Marshal Ney — commander of the left wing of Armée du Nord and tasked with overseeing the initial attack on Wellington’s lines — or his corps commanders, Wellington rarely if ever delegated. The exception at Waterloo was the control of the cavalry, which he delegated to his nominal second-in-command, Lord Uxbridge. All day at Waterloo Wellington gave orders to the infantry and artillery units as he saw fit, but left the cavalry to Uxbridge. Wellington did not use the corps as tactical entities — and we do not necessarily hear of the corps commanders. Instead, following his usual practice of issuing orders directly to divisional and other commanders, Wellington expected to move around the battlefield, with his staff in his wake, to wherever his presence was needed. While this allowed his commanders less scope for initiative, this type of leadership was perfectly feasible for a commander overseeing a defensive strategy — as Wellington was — but it would have been difficult to sustain if the Anglo-Allied force had been fighting an offensive battle. Napoleon had the initiative. Even on such a small battlefield as Waterloo, Napoleon could not, even if he had been inclined, lead and encourage every assault, making delegation to his commanders essential.

Battle tactics

Precision in military manoeuvres was crucial to the armies of the early nineteenth century, especially to infantry, which formed the bulk of all the forces engaged. Muskets, the principal infantry weapon, were only effective at limited range, perhaps not much more than 100 yards. This meant that in the battles of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century opposing armies often fought at close quarters. British drill manuals therefore set out how to deploy in line, to ensure that the greatest firepower might be concentrated on the enemy — marching in column until close at hand was one tactic, as it was much easier to advance in this way rather than in a long, extended line. At Waterloo, the allied army was deployed over a front of some two to three miles, in great density, perhaps 24,000 men to the mile.

British infantry and musket fire

There has been an argument that, during the Napoleonic Wars, the British defeated the French by using continuous, well-ordered volleys of musket fire, with their troops lined up in two or three ranks, as opposed to a continuous fire (that has been associated with the Prussian army). It is now believed that British success had another basis. The evidence of military memoirs suggests it was a common practice for British soldiers to hold their fire until very close, firing a single volley and then charging with bayonets. Sources are difficult to assess, but suggest that British infantry in fact used a wider range of different tactical practices, that they were characterised by an increased aggressiveness and a corresponding reluctance to fire — what musket fire there was, was either a response to the enemy’s fire or was a preparatory action before a charge with bayonets.

Bayonet charges

This reliance on a bayonet charge also seems to have been a departure from earlier practice, and distinctive to the British, even if not new to European warfare. There was a simple tactic: to wait until the distance separating the two forces had been reduced to where, when the fire was finally delivered, it could not help but be effective, if not overpowering, and then to charge in with bayonets while the enemy was still recovering from the volley. This was achieved by control: officers held back the aggression of their men until the very last minute. By avoiding a prolonged exchange of fire, loss of control of command was minimised. Many memoirs point to the coolness of the British infantry: their silence was no accident, and was the result of determined efforts by officers. It was hard to redeploy forces in the face of battle: movements of large bodies of men took time. Careful drill, however, enabled lines of British infantry and others to form squares rapidly, an effective defence against cavalry.

French tactics

The French, on the other hand, had a different philosophy on how to manage the morale of their men. They led them into battle, staking all on the ferocity of a first assault — whipping soldiers into a frenzy to exert themselves to their physical limits. There was a psychological problem, however, everything was committed to the first assault — and if it were unsuccessful, the soldiers were more liable to break. French success, however, came from Napoleon’s careful planning of operations and French tactical superiority. He orchestrated the movement of large bodies of men so that the enemy frequently found itself facing vastly greater numbers of men either at the start of the battle or at a critical point. French success was based on the impact of columns of infantry, preceded by swarms of skirmishers. It is thought that French methods facilitated a furious initial attack; but they also allowed for more individualism, which increased the chances of an advance becoming a prolonged firefight — which was when officers were likely to lose control.

What were the differences between forces?

There were other crucial differences between British and French troops. The British rank and file were mainly volunteers who had enlisted for a period of time. The French filled their armies with conscripts: as each cohort reached 20, they were enlisted — although, when manpower became scarce, as in 1813, levies of younger men were imposed. Napoleon’s army at Waterloo included many veterans who had returned to the flag; while the Anglo-Allied army, while having a core of experienced troops, had many, particularly from north Germany, that had only the most basic training. It was for this reason that Wellington was to distribute experienced troops across the field, mixing up national contingents as well, in that the more seasoned forces could set an example to the others.

How long did battles last?

Early nineteenth-century battles might have a swift conclusion, or, like the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, go on for days. The troops who fought at Waterloo had been engaged in manoeuvres, if not actions, over the preceding week: Waterloo, itself, was the culmination of direct engagements between the armies that began with Napoleon’s invasion of the Low Countries on 15 June. Memoirs are clear that the forces that were lined up to fight on 18 June saw the battle as an inevitable conclusion to the engagements of the preceding days — and that they would continue to fight until their job was completed and victory achieved.

Orders

Under conditions of battle, the normal systems used by the British army was no longer appropriate. The general commanding issued, through his Adjutant General, orders to regimental officers, who came each day to headquarters to receive them — and they were then read or relayed to the men of regiments as they assembled. The Quartermaster General was responsible for issuing orders for the movement of troops — although during the press of battle, orders would come direct from the commanders. We have very few orders actually written on the field of battle: one, by Wellington, relates to Hougoumont and is typical of the way in which he did this. In the circumstances of battle, he wrote, in pencil, on small squares of parchment — which might then be carried by his aides-de-camp or others with sufficient authority to commanders. Other orders must have been given verbally.

Document 1: Copy of a memorandum for the Deputy Quartermaster General: Movements of the army, Brussels, 15 June 1815

General Dornberg’s brigade of cavalry and the Cumberland Hussars to march this night upon Vilvorde [Vilvoorde] and to bivouac on the high road near to that town.

The Earl of Uxbridge will be pleased to collect the cavalry right upon Ninhove [Ninove], leaving the 2nd Hussars looking out between the Scheldt and the Lys.

The 1st division of infantry to remain in its present situation but in readiness to march in a moment’s notice.

The 2nd division of infantry will collect this night at Ath and adjacents and to be in readiness to move at a moment’s notice.

The 3rd division to collect this night at Braine le Comte and to be in readiness to move at the shortest notice.

The 4th division to be collected this night at Granmont with the exception of the troops beyond the Scheldt which are to be moved to Audenarde [Oudenaarde].

The 5th division, the 81st Regiment and the Hanoverian Brigade of the 6th division to be in readiness at Bruxelles [Brussels] to march at a moment’s notice.

The Duke of Brunswick’s corps to collect this night on the high road from Bruxelles to Vilvorde.

The Nassau troops to collect at day light tomorrow morning on the Louvain road and to be in readiness to move at a moment’s notice.

The Hanoverian brigade of the 5th division to collect this night at Hal [Halle] and to be in readiness at daylight tomorrow morning to move towards Bruxelles and to halt on the high road between Alost and Assche [Asse] for further orders.

The Prince of Orange is requested to collect at Nivelles the 2nd and 3rd divisions of the army of the Low Countries and should that point have been attacked this day to move the 3rd division of British infantry upon Nivelles as soon as alerted.

This movement is not to take place until it is quite certain that the enemy’s attack is upon the right of the Prussian army and the left of the British army.

Lord Hill will be so good as to order Prince Frederick of Orange to occupy Audenarde with 500 men and to collect the 1st division of the army of the Low Countries and the Indian brigade at Sottenghem [Zottegem] so as to be ready to march in the morning at daylight.

The reserve artillery to be in readiness to move at daylight.

[University of Southampton Library MS 61 Wellington Papers 8/2/4, with some additions from Wellington Papers 8/2/5. Crown copyright: reproduced by courtesy of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.]

Document 2: Wellington writes about Waterloo

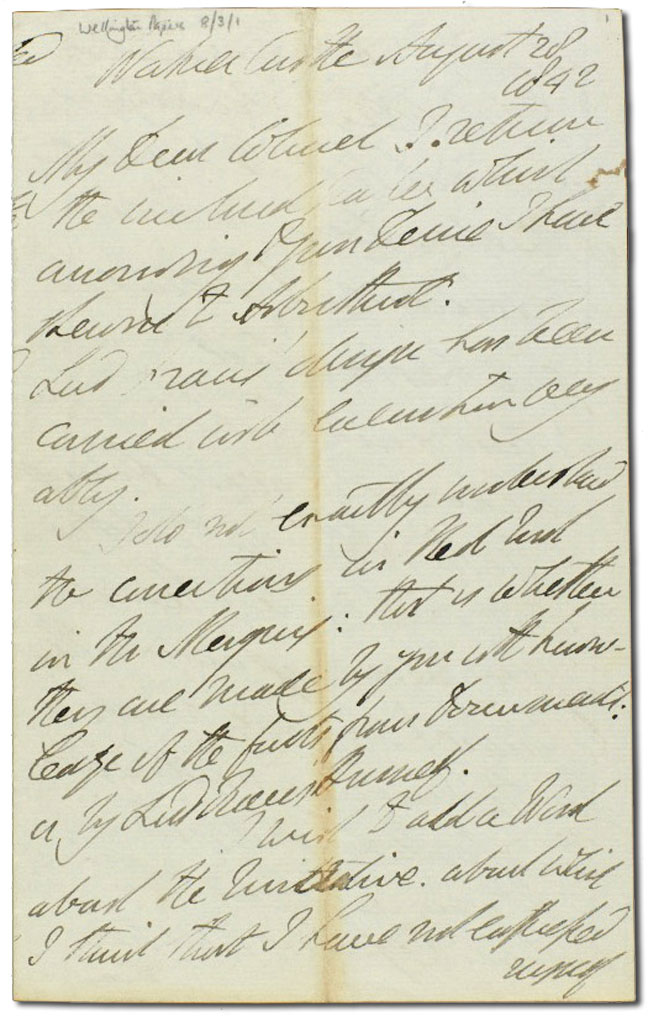

In this letter from Wellington to Lieutenant Colonel John Gurwood, the editor of his Dispatches, 28 August 1842, the Duke writes about Waterloo.

‘I wish to add a word about the initiative, about which I think that I have not expressed myself clearly. All acquainted with military operations are aware that the initiative of the operations between two armies en presence [facing each other] is a great advantage, of which each party would endeavour to avail himself.

We the allies in the Netherlands and on the Meuse in 1815 were necessarily on the defensive! We were waiting for the junction and co-operation of other large armies to attain our object.

But our defensive position did not necessarily preclude all idea or plan of attack upon the enemy.

The enemy might have so placed himself as to have rendered the attack of his army adviseable and even necessary. In that case we must and we should have taken the initiative!

But in the case actually existing in 1815 the enemy did not take such a position. On the contrary he took a position … in which his numbers, his movements, his designs would be concealed, protected and supported up to the last moment previous to their execution, by his formidable fortresses on the frontier.

We could not attack this position without being prepared to attack this superior army so posted, and to carry on at least two sieges at the same period of time.

We could not have the initiative therefore in the way of attack.

We could have it and we had it in the way of defensive movement. But … such movement must have been founded upon hypothesis: our original position having been so calculated for the defence and protection of certain objects confided to our care, any alteration previous to the first movement of the enemy, and the certainty that it was a real movement, which is much more than an hypothesis, must have exposed to injury some important interest.

Therefore no movement was made till the initiative was taken by the enemy and the design of his movement was obvious. If any movement had been previously made it would have been what is commonly called a false movement!

And whatever people may think of Bonaparte, of all the chiefs of armies in the world, he was the one perhaps in whose presence it was least safe to make a false movement!

… Therefore I did not desire or order a movement till I knew on the 15th that a movement had been made, and its direction, although I knew for days before that the whole army with Bonaparte at its head was on the frontier.

When I was certain of the movement and its direction, I ordered the march and it is obvious that I was in time! And if foolish accidents had not occurred, upon which I ought not to have reckoned, the whole army would have been at Quatre Bras on the 16th before the battle commenced in that part of our position.’

[University of Southampton Library, MS 61, Wellington Papers 8/3/1: Crown copyright, reproduced by courtesy of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.]

Share this

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free