Contraceptive method choices

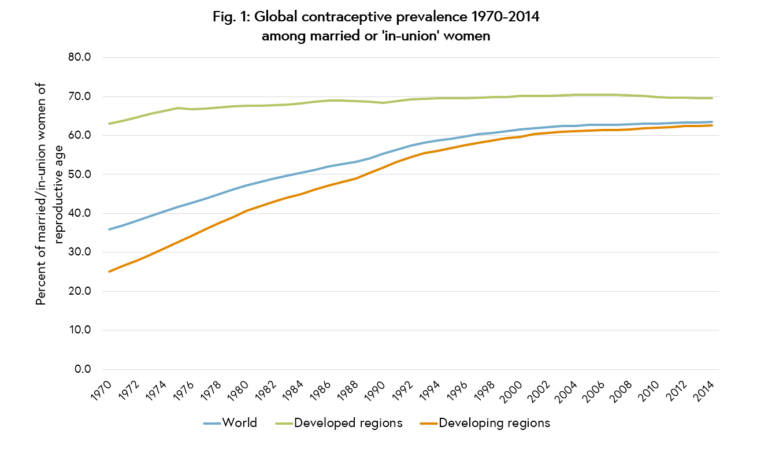

The use of contraception has increased rapidly across the world since the first regulatory approval of the contraceptive pill in the United States in 1960. In this step, Dr Kathryn Church and Dr Christopher Smith discuss the different contraception options that are available and how they have changed over time. Today, there are over 750 million women purposefully aiming to space or limit the number of children they have.1 While contraceptive prevalence is highest in high income countries, it has also increased rapidly in poorer countries over the past fifty years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Global contraceptive prevalence 1970-2014 among married or ‘in-union’ women. United Nations (2015).1

Figure 1. Global contraceptive prevalence 1970-2014 among married or ‘in-union’ women. United Nations (2015).1

Contraceptive options

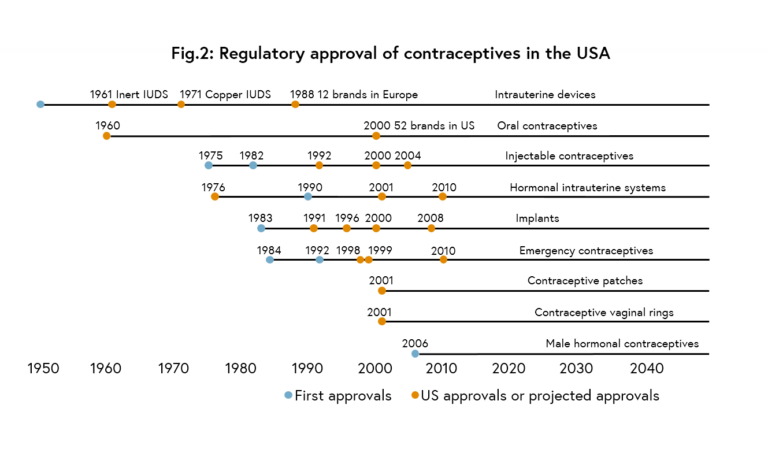

In line with increases in overall contraceptive use, the range of modern contraceptive methods available to women has also flourished (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regulatory approval of contraceptives in the USA. Adapted from Bongaarts and Johannsen (2002).4

Contraceptive options today include:

- male or female sterilisation, the two methods that permanently prevent pregnancy

- the intra-uterine device (IUD), a small piece of plastic wound with copper wires that is inserted into a woman’s uterus and provides protection from pregnancy for at least 10 years

- hormonal methods, which require the woman to take a dose of oestrogen and/or progestogen hormone to either prevent ovulation or to thicken the cervical mucous and prevent fertilisation; they include implants, injectables, pills, intra-uterine systems, patches and vaginal rings

- barrier methods, including condoms and diaphragms; condoms are the only method that also protect against sexually transmitted infections

- fertility awareness-based methods, which rely on a woman tracking menstrual cycles or physical symptoms and avoiding unprotected sexual intercourse on fertile days

- temporary methods, including emergency contraceptive pills (also hormonal) which can usually be taken up to five days following unprotected sexual intercourse; or the lactational amenhorroea method (LAM), with which fully breastfeeding women can rely on a temporary period of infertility for six months following childbirth, providing their menstrual periods have not returned.

The characteristics of the different methods now commonly available across different world regions are highlighted in the See Also section.

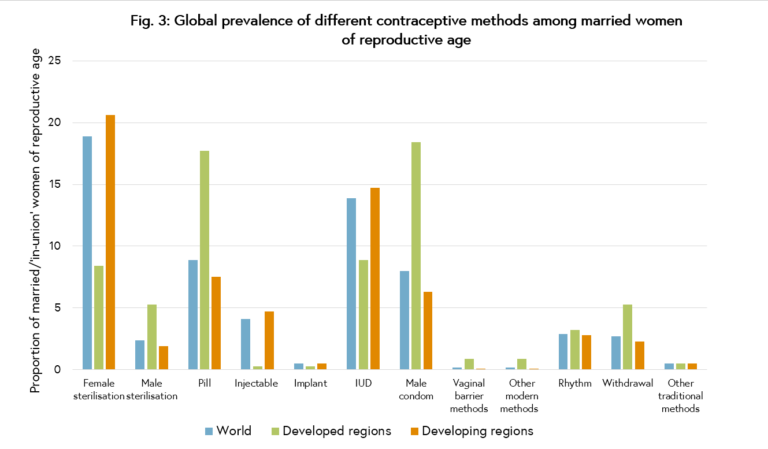

Changes in practice

Over the course of the last century there has been a shift away from traditional and less effective methods, such as withdrawal, periodic abstinence or the condom, to modern methods that more reliably prevent pregnancy. Today, the most commonly used contraceptive is female sterilisation, used by 19% of married or ‘in-union’ women, followed by the IUD, used by 14% of women. These figures, however, mask considerable variation in the types of methods used in different regions and countries. The large populations of contraceptive users in India, China and North America rely primarily on sterilisation or the IUD, pushing up global averages. In Europe and Oceania, most women rely on the pill (21% and 14% respectively), while in Africa, the most common methods are pills and injectables (8% each). While not included in these global estimates, which are measured among married women, condoms are a common method of choice for young people across all world regions.2

Figure 3. Global prevalence of different contraceptive methods among married women of reproductive age. United Nations (2013).5

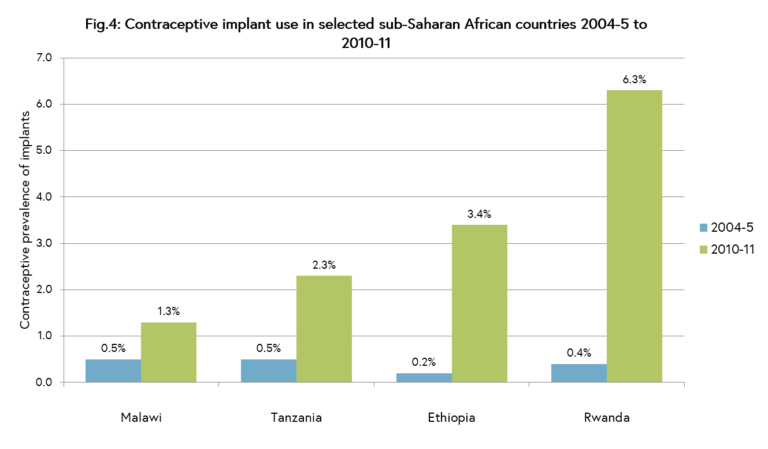

Contraceptive options and preferences are also changing over time. Contraceptive implants, which were given regulatory approval in the 1990s, are increasingly being used across all world regions due to their very high efficacy in preventing pregnancy, ease and duration of use, and relatively good side-effect and safety profile. While prevalence of implants still remains very low compared to other methods, the availability of lower-cost formulations has allowed the method to be promoted in some of the world’s poorest countries (see Figure 4). There are also new types or formulations of contraceptives continually emerging which aim to increase ease of use, reduce costs, and minimise bothersome side-effects. For example, an auto-disposable injectable, the Sayana Press, was recently approved offering a new formulation of the progestogen-only injectable Depo-Provera® which can be self-administered.3

Figure 4. Contraceptive implant use in selected sub-Saharan African countries 2004-5 to 2010-11. Jacobstein (2013).6

What next?

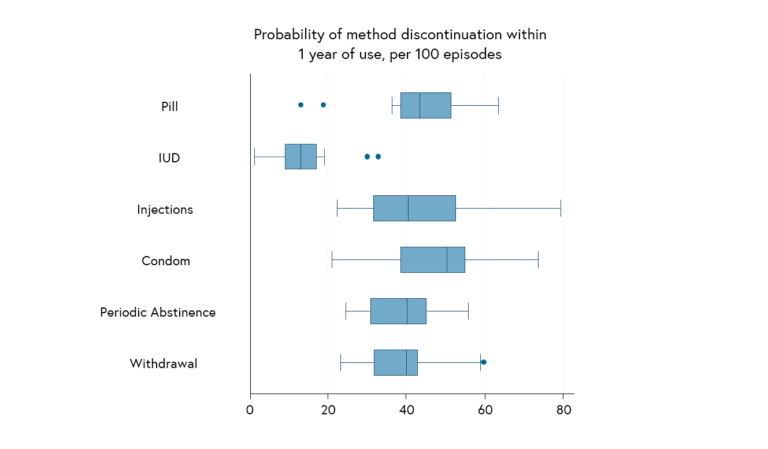

As demand rises across the world for effective and user-friendly contraceptives, there is now a clear imperative to ensure the wide range of method options are made available to all women and their partners. Too often contraceptive choice is still highly restricted in the world’s poorest countries, due to a range of factors including costs, lack of provider knowledge or skills, supply chain problems, failure to promote and raise awareness of new methods, or lack of political action to introduce them. Greater efforts are also needed to increase male involvement in family planning. While sterilisation can be performed on both men and women, although only 2% of men worldwide have undergone the procedure. Given high rates of ‘method discontinuation’ across many countries, i.e. abandonment of family planning when still needing or desiring to prevent pregnancy, there is also now a global push to promote use of long-acting, reversible methods of contraception (known as LARCs), in particular implants and the IUD. While shorter-acting options will always be needed, in particular for young and unmarried women, LARCs are popular because users are more likely to continue method use and thus effectively prevent pregnancy in the long-term (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Probability of method-related discontinuation at 12 months per 100 episodes, 19 countries. Ali, Cleland & Shah (2012).7

Before we move on to thinking about how and where people can obtain the methods highlighted in this article, try to think about what more can we can do to address some of these issues. What are some of the barriers to contraceptive choice in settings where you live? Are you aware of any strategies that have positively influenced attitudes towards, or increased take up of, a particular contraceptive method?

Share this

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free