Provision of Maternal Health Care During Labour and Childbirth

Why is quality of care important?

Despite impressive improvements in maternal and newborn health (MNH) over the last two decades, progress has been uneven with worsening inequities within and across countries. In 2015 alone, 5.6 million women and babies died during pregnancy, delivery or in the following 4-6 weeks afterwards 1, 2, 3. This scale suggests that further reduction of maternal and newborn deaths is essential for sustainable development 4. Achieving the targeted reduction of the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births 5 will require near universal coverage of institutional deliveries and timely detection and management of birth complications, as most maternal and newborn deaths occur at birth or within 24 hours of birth 6.

An increasing body of evidence suggest that getting women to health facilities is not enough, the quality of care (QoC) that she receives at the facility-including ensuring her right to high-quality antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care is essential 7, 8. This is particularly timely given the increasing momentum towards universal health coverage across the world 9, 10. However, in many Low- and Middle-Income countries (LMICs), research also shows that greater access to institutions for deliveries does not necessarily translate into reductions in maternal or perinatal deaths. For example, a multi-country study found higher than expected maternal mortality in hospitals in high-mortality LMIC countries, despite the availability of essential medicines, suggesting gaps in clinical management or treatment delays for hospitalised women who had life threatening obstetric complications (obstetric near-miss)11. Studies from India, Malawi and Rwanda have also found that greater access to institutional deliveries was not associated with reductions in neonatal mortality rate, a finding researchers attribute to poor quality of care 12, 13, 14.

What is Quality of care during labour and childbirth?

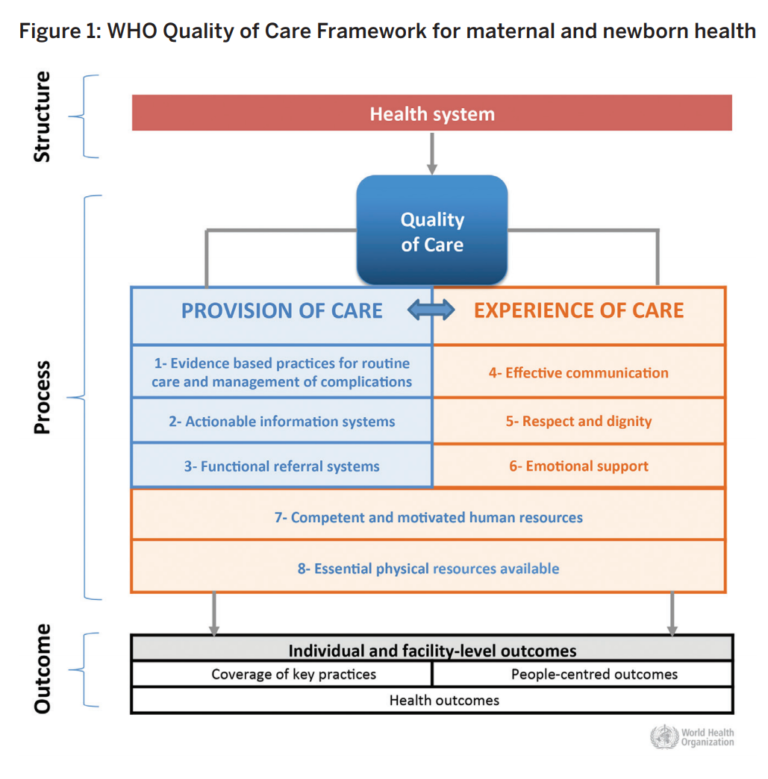

The World Health Organization (WHO) framework (figure 1) for QoC in MNH conceptualises quality as both provision of evidence-based care and positive experiences for women seeking care.xv The WHO framework recognises the importance of robust information systems to capture data on QoC, the need for effective referral systems in case of emergencies and effective interpersonal care so that women receive dignified and respectful care. However, respect, dignity and emotional support, although integral to ensuring positive birth experiences have been largely overlooked in research, policy, programmes and practice 16.

How can you identify health system bottlenecks and potential solutions for improving quality of labour and childbirth care in your country at the national level?

Quality is multi-dimensional and poor QoC can arise due to many reasons. For example, a lack of material resources, poor infrastructure, inadequate numbers of properly trained staff, limited knowledge and clinical management skills, policy constraints, inappropriate applications of technology, inability of organisations to change, failure to align health workers incentives and others. Given such diverse challenges, improving QoC during labour and childbirth can seem daunting, but it is possible. Implementation research methods can be systematically applied to identify bottlenecks for scaling up quality care during labour and childbirth. Existing tools can be adapted to national contexts and systematically used to explore health system bottlenecks and solutions for scaling up quality maternal and newborn care.

Quality care during labour and birth: a multi-country analysis of health system bottlenecks and potential solutions (See Sharma G, et al (2015))

A recent study done by researchers at the LSHTM utilised a health systems approach to examine implementation bottlenecks across seven “building blocks” for strengthening health systems: service delivery, health workforce, information, medicines, financing, governance, community ownership and partnership 17. Researchers used quantitative and qualitative methods to collect information, assess health system bottlenecks and identify solutions to scale up MNH interventions in 12 high burden countries. Through this exercise, researchers identified bottlenecks for the provision of Skilled birth attendance (SBA), Basic Emergency Obstetric care (BEmOC) and Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric care (CEmOC) services in all the countries.

Critical findings

The most critical bottlenecks and solutions for improving QoC are:

| BOTTLENECK | SOLUTION |

|---|---|

| Health financing | Removing user fees to address financial barriers and strengthening national financing mechanisms |

| Health service delivery | Improving QoC for maternity services and exploring innovative public-private partnership approaches |

| Health workforce | Task shifting, improved human resource planning and production and improving training quality |

What does poor quality of care look like at the frontline? – An example from Uttar Pradesh, India.

In another study, LSHTM researchers utilised clinical observations to measure quality of essential labour and childbirth care across public and private sectors hospitals in Uttar Pradesh, India 18. In 2012–2013, Uttar Pradesh was the Indian state with the largest population and the second and third highest levels of maternal and neonatal mortality, respectively. Researchers investigated the application of evidence-based practices, use of potentially harmful interventions and woman-centred respectful maternity care practices during the birthing process.

Overall, quality of care was found to be poor across the studied facilities (Sharma G; B-WHO 2017).

- Quality of essential care during labour and childbirth was found to be deficient across all facilities

- Only 45% of recommended clinical practices were completed among women giving birth in the private sector compared with 33% in the public sector

- Private-sector clients received 40% of the recommended obstetric care practices and 51% of the recommended neonatal care practices – compared with 28% (P=0.01) and 39% (P=0.02), respectively, in the public sector

- Unqualified personnel (i.e. dais, traditional birth attendants, cleaners, community health workers, other helpers,) were observed attending to 59% of all deliveries, 65% in the public sector and 41% in the private sector

- Life-saving clinical practices such as screening for pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, partograph use for monitoring labour, and active management of the third stage of labour were rarely observed.

- Poorer quality care within maternity facilities was observed during weekends

What could be done to improve quality of care in this setting?

- Systematic effort to measure and identify existing quality gaps during labour and childbirth, is required in India’s high-burden states.

- Further research is needed to explore the high prevalence of untrained personnel providing maternity services and why widespread non-adherence to recommended protocols occurs in health facilities.

- Tailored quality-improvement initiatives are required for facilities in both public and private sectors – with the regular auditing of processes of care linked to functional accountability mechanisms.

What about respectful maternity care?

Typology of mistreatment of women during childbirth

- Physical abuse

- Sexual violence

- Verbal abuse

- Stigma and discrimination

- Failure to meet professional standards of care

- Poor rapport between women and providers

- Health systems conditions and constraints

(Bohren et al 2015)

Further analysis of this data combined with prepared comments by observers (qualitative notes) provided insights into the nature and context of mistreatment at maternity facilities 19. Researchers found that all women in the study encountered at least one indicator of mistreatment. There was a high prevalence of not offering birthing position choice (92%) and routine manual exploration of the uterus (80%) in facilities in both sectors. Private sector facilities performed worse than the public sector for not allowing birth companions (p = 0.02) and for perineal shaving (p = < 0.001), whereas the public sector performed worse for not ensuring adequate privacy (p = < 0.001), not informing women prior to a vaginal examination (p = 0.01) and for physical violence (p = 0.04). Prepared comments by observers helped to identify additional themes of mistreatment, such as deficiencies in infection prevention, lack of analgesia for episiotomy, informal payments and poor hygiene standards at maternity facilities.

How do we improve respectful maternity care in this setting?

- A systematic and context-specific effort to measure QoC, including mistreatment is required.

- A training initiative to orient all maternity care personnel to the principles of respectful maternity care would be useful.

- Innovative mechanisms to improve accountability for respectful maternity care are required.

- Participatory community and health system interventions to support respectful maternity care are needed.

- Lastly, long-term, sustained investments in health systems are needed so that supportive and enabling work-environments are available to front- line health workers.

Share this

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Improving the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents: from Evidence to Action

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free