The Organisation of the Slave Trade on the African Coast

To understand the complexity of the transatlantic slave trade one could begin by studying the large variety of merchandise European and American slave ships carried to the African coast.

Slave traders did not normally themselves capture and enslave black Africans; instead they obtained their human cargo through barter with coastal middlemen. For every captive, these brokers demanded an assortment of exotic goods, the precise composition of which depended on the specific needs and fancies of consumers in the region where trading took place.

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, the first published African in Britain, was sold into slavery as a teenager. In his autobiography, he explained how he saw the negotiations over his life between and African and European slave-traders.

“The next day he took me on board a French brig; but the Captain did not chuse to buy me: he said I was too small; so the merchant, took me home with him again. The partner, whom I have spoken of as my enemy, was very angry to see me return, and again purposed putting an end to my life; for he represented to the other, that I should bring them into troubles and difficulties, and that I was so little that no person would buy me.The merchant’s resolution began to waver, and I was indeed afraid that I should be put to death: but however he said he would try me once more.A few days after a Dutch ship came into the harbour, and they carried me on board, in hopes that the Captain would purchase me.–As they went, I heard them agree, that, if they could not sell me then, they would throw me overboard.–I was in extreme agonies when I heard this; and as soon as ever I saw the Dutch Captain, I ran to him, and put my arms round him, and said, “father, save me.” (for I knew that if he did not buy me, I should be treated very ill, or, possibly, murdered) And though he did not understand my language, yet it pleased the ALMIGHTY to influence him in my behalf, and he bought me for two yards of check, which is of more value there, than in England.”

“The kind we want must be in colours mostly red, on blue ground with red & blue stripes as they are for Old Callabarre & you must well know the patterns”.

He knew specifically what Africans slave-traders at Old Calabar (in present-day Nigeria) wanted. Frequently, trading involved putting together a selection of different items, which also required careful thought. Ottobah Cugoano described being sold for, “a gun, a piece of cloth, and some lead”. Knowledge of how to trade came from experience in negotiations and the development of long-term social and economic relationships.

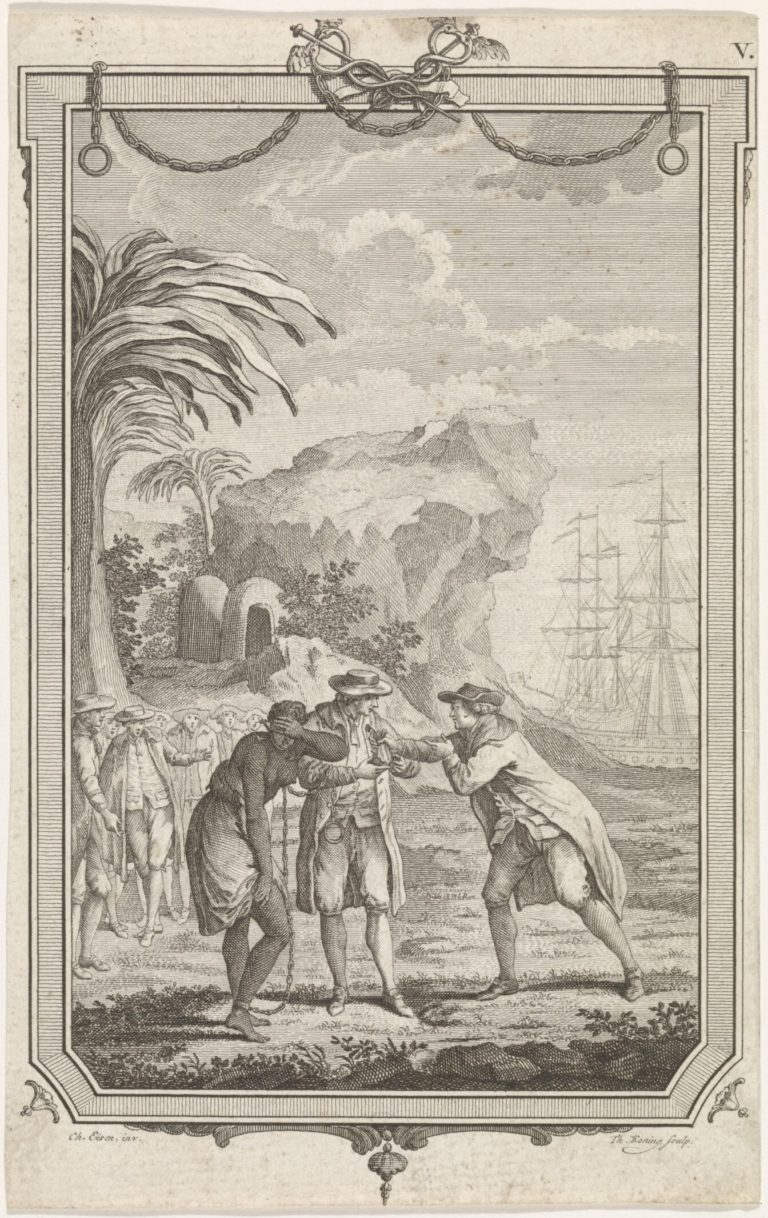

Slave trade, print maker: Theodoor Koning after design by: Charles Joseph Dominique Eisen. Public domain

Slave trade, print maker: Theodoor Koning after design by: Charles Joseph Dominique Eisen. Public domain

Slave traders therefore had to know exactly what kind of goods were in demand in the African ports they intended to visit. Why did Africans want goods for slaves? First, it is important to understand that before 1900, African economies were not monetised; goods were exchanged through barter. The most popular item in all African regions were colourful textiles, which slave traders predominantly obtained from Asian manufacturers. Guns and gunpower and different kinds of liquor (rum, brandy or gin) were other goods in high demand, although not everywhere to the same degree. Slave ships furthermore carried varying assortments of smaller goods to Africa, including knives, iron bars, cowrie shells, glass beads, tobacco, unwrought metal and metallic objects, copperware, earthenware and glasswork. But within these broad categories, there were always regionally specific variations in shape, colour, texture and quantity. Any ship captain who did not know what his African trading partners wanted risked heavy losses on his slaving venture.

When slave ships left their home ports for the African coast, they were practically floating warehouses, filled with expensive goods sourced from all corners of the world. Textiles mainly came from Asia, although some were manufactured in European countries. Denmark produced trade guns for the European slave trade, while Sweden and Belgium contributed iron. Cowrie shells came exclusively from the Maldives in the Indian Ocean and were carried to Europe by British and Dutch East India Company ships to be loaded on vessels destined to West Africa. Portuguese slave traders supplied African consumers with Brazilian tobacco, gold dust and rum (aguardente). Rhode Island slave traders carried American rum, while British, French and Dutch slavers usually bought their alcohol stocks from local distillers. When these goods reached Africa, coastal brokers forwarded them to their slave suppliers further inland. In this way, the slave trade was an immensely complex business that involved manufacturers, middlemen, enslavers and consumers in at least five different continents.

Africans did not usually demand goods that they could produce better or more cheaply themselves. The commodities that African traders imported were thus either luxury goods or essential goods that filled a niche in the African market. Asian and European textiles were high-quality products, which African consumers fancied because of their texture and colourful patterns. In some regions, African rulers found a use for European weaponry in warfare and slave raiding, but generally guns and gunpowder were symbols of power and were, like alcohol, used in rituals and ceremonies. Other goods served more essential purposes. Some African peoples used imported iron to make agricultural tools and weapons. Cowries and beads served as currencies in local markets, although sometimes they were also used for decoration. Just as foreign slave traders used these goods to buy captives on the coast, within Africa powerful traders and rulers used expensive commodities to acquire people.

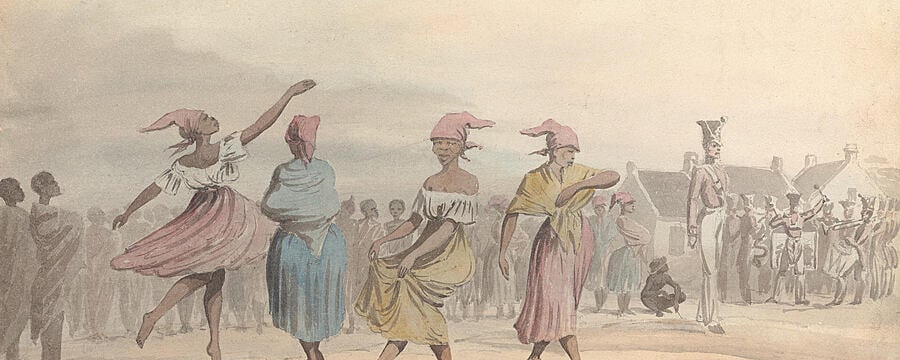

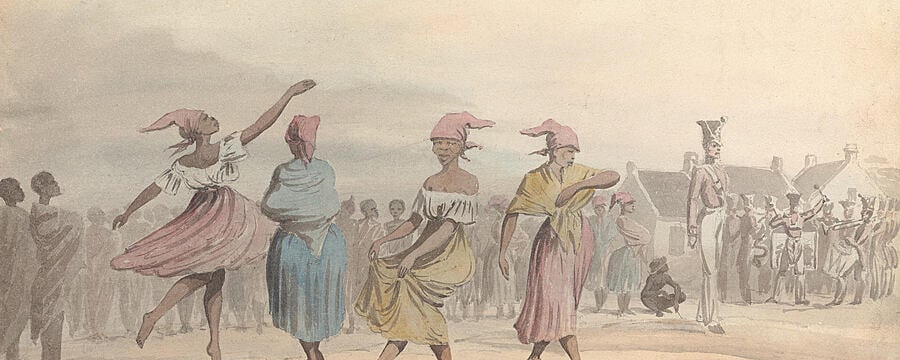

African family separated by European men, John Raphael Smith, after George Morland. Public Domain

African family separated by European men, John Raphael Smith, after George Morland. Public Domain

Slave ships spent several months on the coast buying captives, which meant that the first enslaved Africans on board could spent anywhere from six to twelve months in the ship’s hold before disembarkation in the Americas. The unhealthy conditions of the slave ship exposed them to the risk of disease – and adult males more so than women and children – and epidemics often broke out while ship crews were still purchasing captives in Africa.

To facilitate their slaving business, slave traders and their African partners often invested a great deal in developing relationships of trust. African trading families sent their children to England, France, Portugal and the Netherlands to be educated in European cultures and languages. Where European merchants were allowed the settle on land, they married into local families, which over time created a mercantile elite of so-called Eurafricans. Ship captains and coastal brokers always exchanged gifts while trading. In many African regions, brokers offered free members of their own communities as pawns in exchange for merchandise they had received on credit. These pawns would remain on the ship until the trade was finished and all goods paid off. Sometimes slave traders became impatient with their African suppliers and decided to take off with the pawns enslaved onboard. It was best to avoid this scenario, however, because retaliation awaited the next captain arriving in the African port from which the pawn was kidnapped. Indeed, for African traders there was a clear distinction between their own kin and people who could be legitimately enslaved.

Further reading

- Ottobah Cugoano (1787), Narrative of the Enslavement of Ottobah Cugoano, a Native of Africa; Published by Himself, in the Year 1787.

Share this

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

History of Slavery in the British Caribbean

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free