Modernity, Sexuality and the Self

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas, May 1893. Photograph by Gillman & Co. Public domain.

Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas, May 1893. Photograph by Gillman & Co. Public domain.

Two common assumptions underpin our modern understanding of sexuality. The first is that who we have sex with is governed – to a large degree – by our sexual identity. Most commonly this is whether we are gay, straight or bisexual, although the last decade has seen a proliferation of categories, including asexual to describe those who may have little interest in sex, and pansexual, to denote those who are sexually attracted to individuals independent of their gender. A recent study by the Williams Institute at the University of California, showed that 5.6% of adults in the US Identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual. This compares with 2.1% of the population in Australia, 1.5% in the UK and 1.2% in Norway.

There is little consensus within the scientific community over the precise origin of sexual orientation, although biological causes are currently favoured over cultural influences, with neuroscientist Simon LeVay asserting that orientation results from ‘a cascade-like sequence of interactions among genes, sex hormones, and the cells of the developing body and brain’ (LeVay 2011, p. xii). Following this theory, as a man or woman we are born with an attraction to someone of the same or opposite sex or indeed both or none.

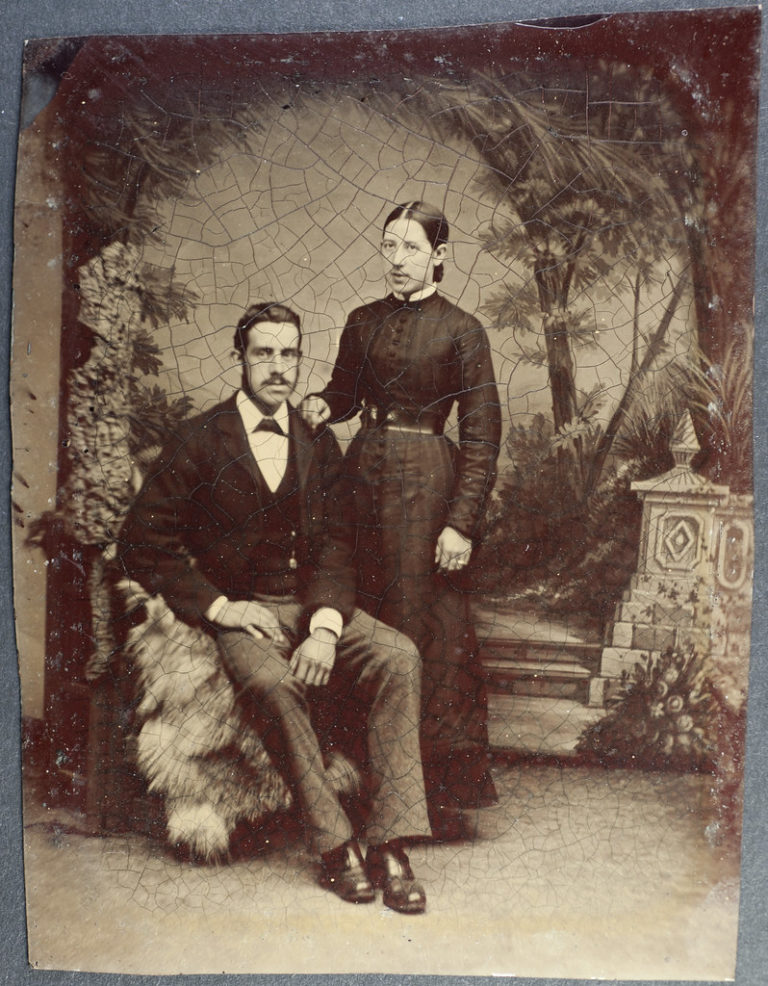

Late nineteenth-century couple. Public domain.

Late nineteenth-century couple. Public domain.

This biological understanding of sexuality corresponds with the second common assumption, that sexuality is a natural force that can be ‘liberated’ by being allowed free expression, or ‘repressed’ through social taboos or legal sanction. For example, the stereotypical perception of the Victorian period is that it was an era of sexual repression, when sex could only legitimately take place within marriage, Shakespeare was bowlderised and as research by Mary Wilson Carpenter has shown, even suspect passages in the Bible printed in very small type or labelled ‘Not Suitable for Family Reading’. Conversely, the 1960s are considered a time of sexual liberation, when the advent of the oral contraceptive pill divorced sex from reproduction, and countercultural youth movements championed ‘free love’ or non-monogamous sex outside of marriage.

‘All we needed was love’ by brizzle born and bred. CC BY-SA 2.0

‘All we needed was love’ by brizzle born and bred. CC BY-SA 2.0

Since the establishment of the history of sexualities as an academic discipline in the 1970s, historians have questioned and complicated these two assumptions – of sexual identity as biological and unchanging, and of sexuality’s ability to be liberated or repressed. As with the category of gender, historians have provided compelling evidence, from a wide range of historical periods and geographical cultures, that the field of human sexuality is subject in profound ways to the cultural meanings in circulation at any particular historical moment. Put simply, society shapes our sexual desires.

The key theorist who has influenced the field is the French philosopher Michel Foucault. In the first volume of his series on the history of sexuality, published in 1976, he argued that sexual identity as we currently understand it is an invention of modernity. Prior to around 1750, he asserted, sodomy had been considered a sin which any man could commit. However, a new compunction to regulate all non-reproductive sexualities resulted in homosexuality being constructed in psychiatric and psychological discourse as an identity. In a now famous passage, he asserted that while the sodomite had been a ‘temporary aberration’, the homosexual was now a species:

‘The nineteenth-century homosexual became a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology. Nothing that went into his total composition was unaffected by his sexuality … Homosexuality appeared as one of the forms of sexuality when it was transposed from the practice of sodomy onto a kind of interior androgyny, a hermaphrodism of the soul.’ (Foucault 1976, p. 43)

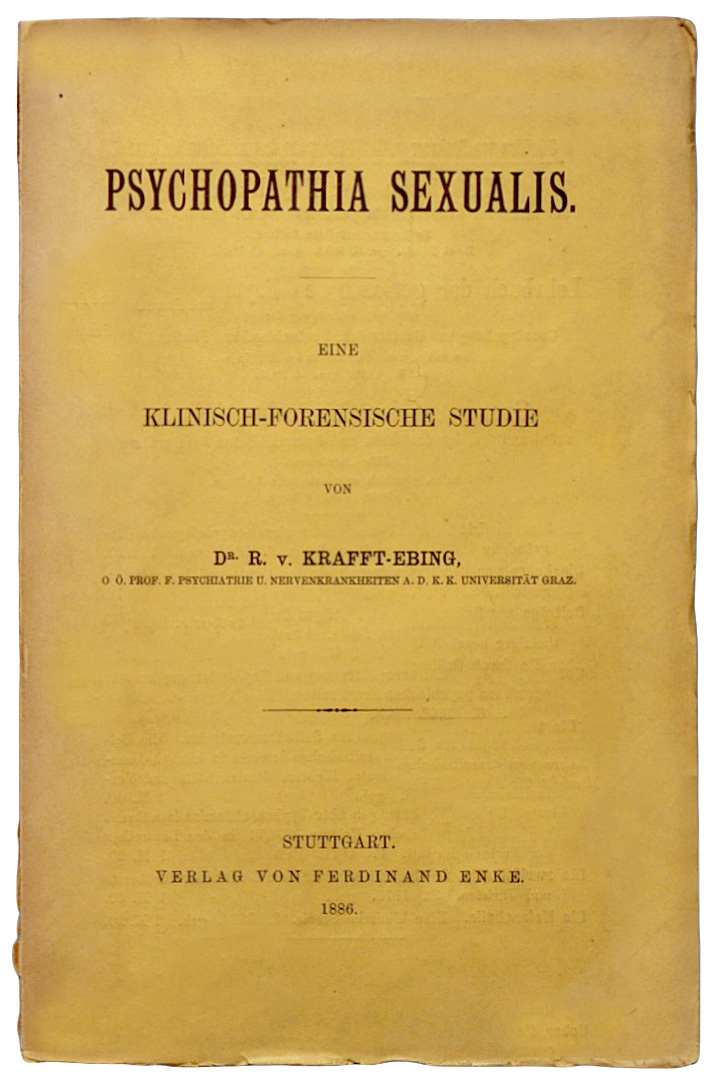

A key early work of sexology, Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. CC by 3.0

A key early work of sexology, Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. CC by 3.0

According to Foucault’s understanding, while we may believe that by adopting a sexual identity we are articulating a facet of our authentic self or liberating ourselves in some way, we are in fact enmeshed within systems of knowledge which seek to regulate our bodily pleasures and desires. The purpose of history, Foucault argued, was not to trace the historical origins of these and other identities, by writing gay or lesbian histories for example, but to reveal their contingency, and commit ourselves to their dissipation.

Foucault’s thesis has not gone uncontested by historians. Some have disagreed over the timing of the shift, Randolph Trumbach, for example, asserting that it was the beginning of the eighteenth century that behavioural patterns of homosexuality and heterosexuality came into existence in Europe, even if the terms themselves were nineteenth-century inventions. Others have taken a contrary, essentialist view, John Boswell suggesting that the three basic categories of sexual orientation – gay, straight, bisexual – have existed throughout history, no matter what they’ve been called. Queer theory has offered a way out of this impasse, literary critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick arguing that actual desire can never be fully represented in regulatory categories, and that we need to keep our understanding of homosexual origins and cultures ‘plural, multi-capillaried, argus-eyed, respectful, and endlessly cherished’ (Kosofsky Sedgwick 1994, p. 44).

A parodic cartoon depicting male and female crossdressing, c. 1780, after a work by John Collet. Public domain.

A parodic cartoon depicting male and female crossdressing, c. 1780, after a work by John Collet. Public domain.

To turn to the second assumption, that sexuality is a natural force which can either be repressed or liberated, Foucault’s work is relevant here too. He argued against what he termed the ‘repressive hypothesis’, the idea that the Victorians were dominated by a ‘restrained, mute and hypocritical sexuality’, and instead asserted that from the eighteenth-century, people have in fact talked about sex as never before. He writes ‘when one looks back over these last three centuries with their continual transformations, things appear in a very different light: around and apropos of sex, one sees a veritable discursive explosion’ (Foucault 1976, p. 17).

‘The Great Social Evil’, Punch 33 (10 January 1857). Public domain.

‘The Great Social Evil’, Punch 33 (10 January 1857). Public domain.

He is not denying that there were new rules of propriety and circumstances in which what was said was strictly controlled, such as between parents and children, teachers and pupils and masters and servants. Or that the modern era saw the use of widespread sexual euphemism – with sex work termed the ‘Great Social Evil’, gonorrhoea and syphilis ‘social diseases’ and masturbation the ‘solitary vice’. However, he nonetheless asserts that the modern period witnessed a steady proliferation of discourses concerned with sex.

The reason for this was that modern capitalism and nation states required the efficient regulation of the reproductive bodies of its citizens. To achieve this, a variety of modern institutions, including asylums, courts, workhouses, hospitals and local government, employed what he termed ‘biopower’, creating a ‘regime of truth’ or knowledge around the body which individuals then internalised, self-disciplining their own desires. For Foucault, the crucial question was not ‘whether one says yes or no to sex’, but what knowledge about sex is being disseminated, by whom, for what purpose, and with what result, in what he terms the ‘polymorphous techniques of power’.

The course this week will introduce some of the different ways in which these ‘polymorphous techniques’ have operated – in social arenas ranging from religiously-conservative nations and apartheid regimes to feminist magazines and queer artworks. However, it will also keep an eye on the injunction of queer theory to be alert, in Matt Houlbrook’s words, to the ‘inchoate nature of social and sexual boundaries’ (Houlbrook 2013, p. 137).

Further Reading

John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality: Gay People in Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 1980)

Michel Foucault, The history of Sexuality: Volume 1. An Introduction (Penguin, 1976)

Matt Houlbrook, ‘Thinking queer: the social and the sexual in interwar Britain’, in Brian Lewis (ed.), British Queer History: New Approaches and Perspectives (MUP: Manchester, 2013), pp. 134-64

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Penguin, 1994)

Simon LeVay, Gay, Straight and the Reason Why: The Science of Sexual Orientation (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Randolph Trumbach, Sex and the Gender Revolution Vol 1: Heterosexuality and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London (University of Chicago, 1998)

Mary Wilson Carpenter, Imperial Bibles, Domestic Bodies: Women, Sexuality and Religion in the Victorian Market (Ohio University Press, 2003)

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free