The Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s

Dr Tanya Cheadle

If we accept that sexuality is not a natural force that can be liberated or repressed, but rather a complex nexus of sexual behaviours and beliefs constructed by society, where does that leave the 1960s and ’70s? Can we think of these decades in terms of sexual liberation?

It is clear that we can no longer trace a simple narrative of progress from the ‘repressed’ Victorians to today. Continuities in sexuality remain as significant as change, with many aspects remaining stubbornly entrenched, or shifting very slowly. These include, for example, discriminatory attitudes towards female rape victims as complicit in their own assault, or the current wave of ‘reproductive puritanism’ restricting women’s access to abortion in countries such as Poland, Chile and Brazil. Furthermore, new sexual possibilities have often been followed by conservative backlashes, bringing with them additional forms of surveillance and regulation.

Pro-choice feminists protesting in São Paulo on the International Women’s Day. Christiensen. Public Domain

Pro-choice feminists protesting in São Paulo on the International Women’s Day. Christiensen. Public Domain

Nonetheless, there is a general consensus among historians that since the Early Modern period, there has been fundamental change in how sexuality is understood and experienced, a process according to Jeffrey Weeks, ‘with its epicentre in the old West, but with powerful resonances on a Global scale’ (Weeks 2016, p. 85). In general terms, this can be conceptualised as a transition from a family-centred reproductive model in the eighteenth century to a sexual system which emphasizes individual agency, posits sex as the key to selfhood and happiness, and is in many respects commodified. The timing of this shift is more contested, with some historians seeing a gradual shift from the end of the nineteenth century and others arguing for rapid change in the 1960s.

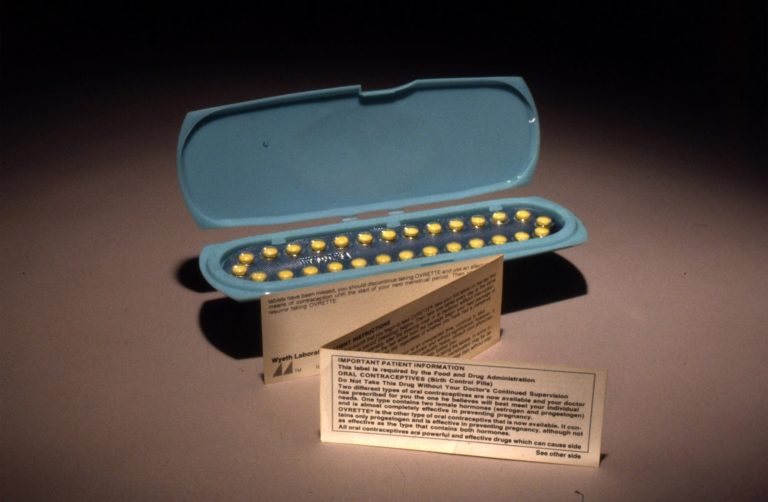

Oral contraceptive pill, 1970s. Public domain

Oral contraceptive pill, 1970s. Public domain

As far as the 1960s is concerned, causation similarly remains a matter of debate, with varying influence ascribed to countercultural youth movements, secularisation, female emancipation, and the oral contraceptive pill, along with other factors. For example, some historians place emphasis on rising levels of premarital intercourse and illegitimate births since World War II, while others foreground the impact of the birth control pill, invented in 1960 and legalised, often only for married women first, in many countries in Europe, North America, Asia and Africa between the 1960s and the 1980s.

While historians remain unsure of many aspects of the changes in people’s actual sexual practices, the rapid shifts in public discourse and norms regarding sex during the long 1960s are evident. Scholars have linked the ubiquity of sexual imagery and discussion with what they call the politicisation of sex from the 1960s – that is to say, the articulation of rights-based claims regarding sexual identity and sexual practice. This was evident particularly in the emergence of radical movements for gay and lesbian liberation.

The disconnection of sexual pleasure from procreation, and the acceptability of this separation, were key underpinnings of the new permissiveness. The breaking of taboos also included the mainstreaming of pornography, including the advent of titles such as Penthouse and Mayfair (founded in 1965 and ’66). It also involved open calls for sexual education, still largely lacking in schools around the world. The exceptionally popular state-sponsored West German film Helga (1967) was exported to Australia, the US, and numerous European countries, and billed in the UK and US as the ‘Intimate life of a young woman’ covering the ‘inquisitive stages’ and ‘courtship’ through to ‘sexual problems’, the ‘physiology of sex’ and finally ‘childbirth’.

Whatever the causes of the changes in the sexual behaviour of the 1960s and ‘70s, what is clear is that they were complex in their manifestation and ambiguous in their results. As Dagmar Herzog has shown, this can be seen explicitly in the shifting attitudes towards sex of the era’s radical activists. Initially, the compatibility of sexual freedoms and left-wing politics had seemed straightforward, encapsulated in popular slogans such as ‘The more I make love, the more I make revolution’, used in the 1968 French student protests.

Theoretical justification for such ideas were provided in a number of European countries by the recuperation of the work of the Freudian and Marxist thinker Wilhelm Reich, who had posited in the 1920s and ‘30s that the sexually satisfied tended towards gentleness and goodness, while the sexually dissatisfied were notable for their cruelty. For example, in 1969, the New Left sociologist Dietrich Haensch asserted that capitalism, fascism and military aggression were the result of the ‘genital weakness’ of the sexually repressed (Herzog 2011, p. 148).

Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957), Austrian-American psychoanalyst, in his mid-20s. Public domain

Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957), Austrian-American psychoanalyst, in his mid-20s. Public domain

Very quickly however, the efficacy of sex as a revolutionary strategy was questioned, including by those on the left. The philosopher Herbert Marcuse argued that the constant injunction to seek sexual pleasure was in fact a distraction technique of consumer capitalism, ‘repressive desublimation’ designed to make proletarian life bearable and keep the worker in a state of oppression.

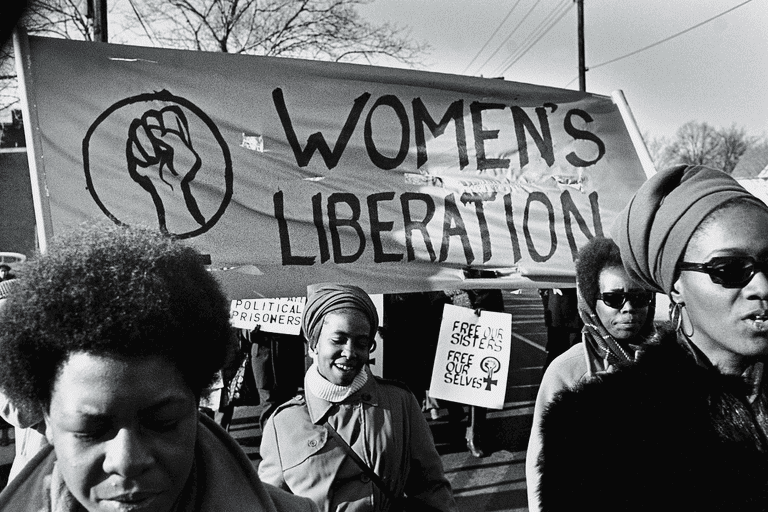

Furthermore, while feminists lobbied for legal reform on divorce, contraception and abortion, thereby precipitating some of the era’s key sexual freedoms, they simultaneously offered a swingeing critique of male sexual behaviour, including rape, domestic violence and sexual harassment and abuse, and of the often male-centred nature of the new culture of permissiveness. They recognised that misogyny was by no means the preserve of conservative men: as one member of the women’s liberation movement in Britain questioned, how was her current marriage distinct from its 1950s counterpart, given she was ‘cooking, answering the phone and rolling her master’s joints’ (Herzog 2011, p. 161)?

Women’s liberation movement by Linda Napikoski, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Women’s liberation movement by Linda Napikoski, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Today, the legacy of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and ’70s remains contested. While the new permissiveness was abruptly reframed by the Aids epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s, amplifying the backlash against sexual freedoms in countries such as the US, the lasting legal changes that the sexual revolution produced (in areas such as abortion, contraception, and sexual education) remain significant in many countries.

Further Reading

Lesley Hall, Sex, Gender and Social Change in Britain since 1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, 2013)

Gert Hekma and Alain Giami (eds), Sexual Revolutions (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014)

Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Enquiry into Freud (Beacon Press, 1975; first ed. 1955)

Uta Schwarz, ‘Helga (1967): West German Sex Education and the Cinema in the 1960s’, in Lutz D. H. Sauerteig and Roger Davidson (eds), Shaping Sexual Knowledge: A Cultural History of Sex Education in Twentieth Century Europe (Routledge: London, 2009), pp. 197-213.

Jeffrey Weeks, What is Sexual History? (Polity Press, 2016)

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free