Global Reproductive Rights and Justice

Dr Maud Anne Bracke

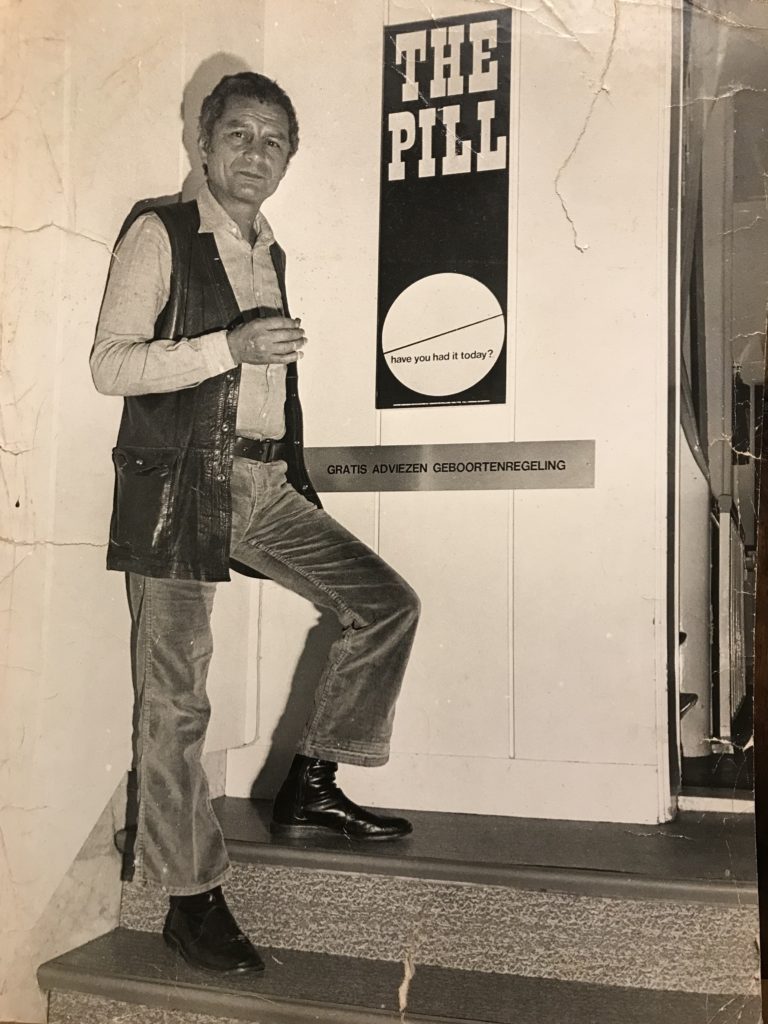

Doctor Frans Wong in his abortion clinic in Amsterdam, the Netherlands early 1970s

Doctor Frans Wong in his abortion clinic in Amsterdam, the Netherlands early 1970s

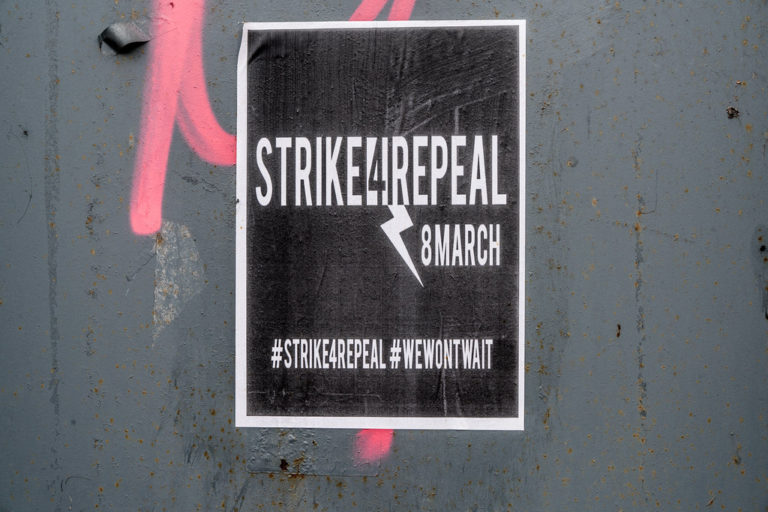

Today’s notion of reproductive rights encompasses access to contraception, safe abortion, sexual education, and family planning, and is strongly intertwined with the notion of reproductive health. Based on the principles of bodily autonomy, it is understood as the undeniable right of individuals to make informed decisions as to whether to have children, with whom, in what circumstances, and when. While ‘reproductive rights and health’ forms an important policy framework for the United Nations and the World Health Organization, in many countries around the world access to safe abortion, sexual education, and contraception remains illegal or limited. One might argue that we are witnessing a current wave of ‘reproductive puritanism’, specifically in countries such as the USA, Chile and Poland. On the other hand, there are cases of recent success for feminists and reproductive rights activists – most notably, the repeal of the 8th Amendment to the Constitution in Ireland in 2018, as a result of which abortion became legal under certain circumstances.

Strike 4 Repeal poster, Ireland, 8 March 2017

Strike 4 Repeal poster, Ireland, 8 March 2017

While women and men have always fought for the right to make their own decisions regarding spacing and number of children, the period after 1945 saw new articulations of reproductive rights principles, as well as rapid legal change in many countries around the world on contraception and abortion from the 1960s onwards. The global dissemination of reproductive rights principles was facilitated by the introduction of the language of human rights by the United Nations after 1945, and it was embedded in the sexual revolution of the 1960s-70s. The invention of the contraceptive pill in 1960 meant that in public discourse, law and medical practice, women rather than men were now envisaged as the key agents making reproductive decisions.

Pro-choice feminists protesting in São Paulo on the International Women’s Day. Christiensen. Public Domain.

Pro-choice feminists protesting in São Paulo on the International Women’s Day. Christiensen. Public Domain.

However, the notion of reproductive rights, as has been pointed out by Black US feminists, indigenous feminists, and women’s organisations in the Global South since the 1970s, is a limited one: emerging primarily out of Western women’s struggles to avoid compulsory motherhood, it did little to acknowledge the long history of the various ways in which women of colour and populations living under colonial rule were denied reproductive autonomy. This included both forced motherhood and the denial of motherhood, with myriad cases of unconsented abortion and sterilisation. The notion of reproductive justice is proposed as an intersectional-feminist alternative: contextualising ‘choice’ in relation to individuals’ situation in terms of race, social class and ability, and proposing a social-justice agenda which includes the right to non-parenting as well as parenting in safe and healthy conditions.

Reproductive Justice for All sign

Reproductive Justice for All sign

Throughout history, it is clear that certain groups in the population are often considered more worthy of procreation than others, or considered more strongly endowed with the capability of making rational and the ‘right’ choices when it comes to family size. Scholars call this the social hierarchisation of reproductive agency according to social class, race, nationality, religion, or ability. Social hierarchisation was most explicit in colonial settings (as for instance in the practices of British colonisers and the dissemination of eugenicist ideas in 19th colonial Kenya), and, as far as Europe in concerned, in the eugenicist policies of Nazi and Fascist regimes, involving, for instance, the forced sterilisation of over 40 000 men and women in 1930s-40s Germany. However, even in more recent times and where the language of reproductive rights is broadly adhered to, such hierarchisation continues to frame, implicitly or explicitly, public debates on family, welfare, demography and gender roles. Think for instance of the discourses around ‘welfare mums’ in the UK, whereby the suggestion of their ‘uncontrolled fertility’ betrays prejudices of working-class female promiscuity and lack of education; or the Italian government’s decision in 2018, accompanied with a message of ‘apocalyptic’ low birth rates in the country, to give heterosexual married couples a free patch of farmland if they have three children, though only if both parents have Italian citizenship and have lived in the country for 10 years.

United Nations General Assembly hall in New York City. Patrick Gruban, cropped and downsampled by Pine / CC BY-SA

United Nations General Assembly hall in New York City. Patrick Gruban, cropped and downsampled by Pine / CC BY-SA

A closer look at the UN debates from the 1970s onwards reveals the centrality of decolonisation in the articulation of reproductive rights principles. Until the 1960s, western actors debated contraception and family planning in the colonies and post-colonial countries through the lens of population management – specifically, they were driven by fears regarding ‘global overpopulation’ and what they saw as excessive demographic growth in the Global South. Numerous family planning interventions in those countries involved unconsented administering of contraception, abortion or sterilisation. In the 1970s, the discourse at the UN shifted, as transnationally operating women’s organisations, alongside a number of Asian, African and socialist countries pushed for a paradigmatic shift. Crucially, they denounced any population management, and the idea of reproductive rights was divorced from demographic concern, proposing instead the extension of the human rights framework to matters of reproductive choice, sexual health, and sexual education.

Further Reading

Chloe Campbell, Race and Empire: Eugenics in Colonial Kenya (Manchester University Press, 2007)

Matthew Connelly, Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population (Harvard UP, 2008).

Silvia De Zordo, Milena Marchesi, eds. Reproduction and Biopolitics (Routledge, 2015)

Paige W. Eager, Global Population Policy: From Population Control to Reproductive Rights (Farnham, 2004)

Betsy Hartmann, Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control (Chicago, 2016, 3rd ed.).

Robert Jutte, Contraception: A History (Polity, 2008)

Mie Nakachi, Rickie Solinger, eds. Reproductive States. Global Perspectives on the Invention and Implementation of Population Politics (Oxford University Press, 2016).

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free