Feminism and Sexuality: LGBT Activism in the UK and the US in the Long 1970s

The histories of feminism and LGBT politics have been intertwined in the western world at least since the 1960s. Both emerged as radical, broadly based social movements amidst the rapid cultural changes of the sexual revolution. They often influenced each other, not least in the gay movements’ adoption of the feminist concept of patriarchy. Both movements radicalised earlier approaches centred on formal legal equality, more fundamentally questioning ingrained social norms, and working towards broader cultural transformation. Moreover, both movements in some respects struggled with diversity within their ranks, and specifically the distinct experiences and voices of lesbian women were often sidelined.

Gay Liberation Front

Gay Liberation Front

Significant advances have been made in terms of the legal rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans (LGBT) people in the last 50 years. This has involved increasing numbers of nations introducing measures to strike down historic and discriminatory laws and practices – although much work still has to be done in advancing LGBT rights in the global context. Yet to paint LGBT activism successes as a straightforward process would be misleading; the staggered nature of legal change in the US or the UK is testimony to this. In terms of male homosexuality, the fact that England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland each removed legal sanctions against private consensual gay sex at different times, or that States with the USA decriminalised at different points throughout the late 20th century, suggests that a nuanced approach to studying LGBT activism is required.

“safari, II” by Newtown grafitti is licensed with CC BY 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

“safari, II” by Newtown grafitti is licensed with CC BY 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

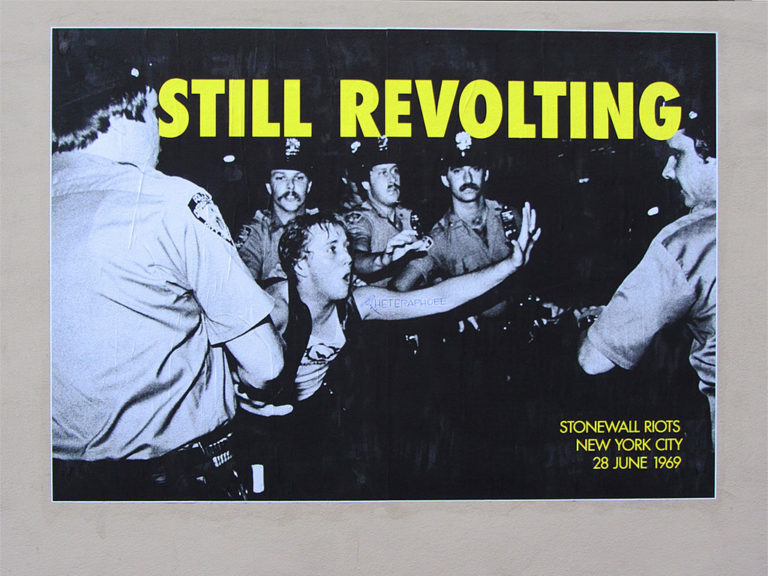

A helpful point of entry for historians of LGBT activism is the Stonewall Riots occurring in New York in 1969, which have been characterised as an explosion of frustration from within a LGBT community to sustain an increasing antagonism towards that community. The Riots which sprung forth from the Stonewall Inn were a match that lit the tinderbox of gay and lesbian activism in the USA. Various groups and organisations had emerged around the country during the 1950, whose aims tended to be related to working within existing social, legal and cultural milieus to generate support across a broad body of institutions (Meek, 2015).

“Historic Photo inside The Stonewall Inn.” by NicestGuyEver is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

“Historic Photo inside The Stonewall Inn.” by NicestGuyEver is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

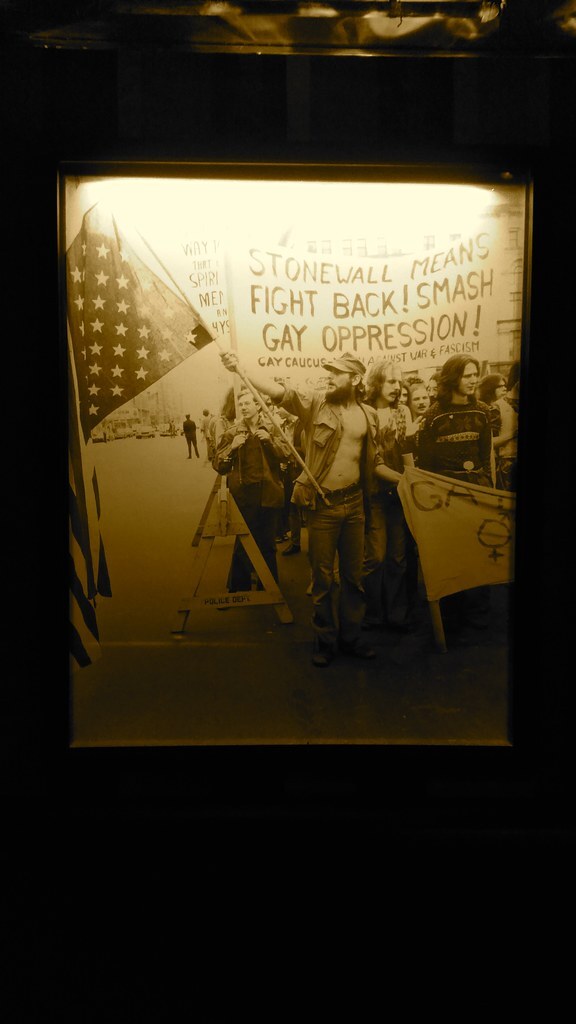

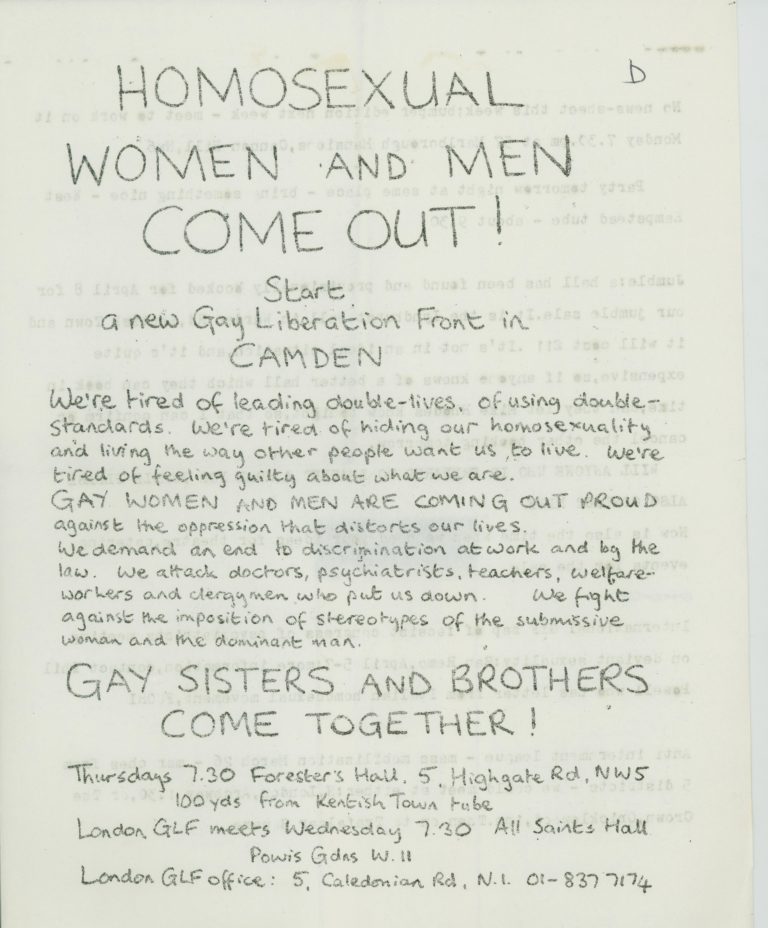

The riots in New York helped to shift focus on to deeply embedded societal prejudices, which would not be shifted simply by changes to legal codes. As a result, a new face of activism was born: liberation. While the equality movement of the 1950s and 1960s saw legal equity as its main ambition, the activists of the liberation movement saw widescale structural and cultural change as theirs. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) emerged in 1969 as a radical movement which saw patriarchy and heterosexism as the main barriers to sexual and personal liberty. Opening its first chapter in New York in 1969, it soon crossed the Atlantic where a chapter opened in London the following year. As articulated in its Manifesto, the overall aim of the UK chapter of the GLF was to go beyond legal equality and its objectives included challenging attitudes and practices that oppressed LGBT people, and instilling pride as the predominant expression of self-identity (Kent, 1999).

While LGBT activism in Britain in the 1950s may have had its roots in the consensus politics of the post-war period, the GLF took its inspiration from more radical cultural political movements, such as the Black Panther movement in the US, radical feminism and the women’s liberation movement, the more radical elements of existing LGBT groups, and the anti-psychiatry movement (Robinson, 2007). Indeed, Huey P. Newton, supreme commander of the Black Panthers, saw significant similarities in the treatment of gay people and African Americans (Black Panther, 21 August 1970, p. 5). While the GLF chapters on either side of the Atlantic were operating within different cultural and legal contexts, they both placed identity and ‘gayness’ at the forefront of their campaigns.

“Gay Pride Hyde Park 1979” by Alan Denney is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

“Gay Pride Hyde Park 1979” by Alan Denney is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

“Gay Pride Hyde Park 1979” by Alan Denney is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

“Gay Pride Hyde Park 1979” by Alan Denney is licensed with CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Source: Creativecommons.org

This involved organising ‘kiss-ins’, ‘sit-ins’, carnivals, parades and marches, and investigated new forms of social organisation that emphasised belonging and community (Weeks, 2015). They disrupted psychiatry conferences attended by those who advocated the ‘treatment’ of LGBT people, and in London in 1971, picketed the religiously conservative National Festival of Light conference, in drag (Robinson, 2007).

Gay Liberation Front sign. Source: LSE Library

Gay Liberation Front sign. Source: LSE Library

The movement was overtly confrontational and political: gay visibility through coming ‘out of the closets and onto the streets’ marked pride, self-confidence, and unleashed a new form of militancy embraced by campaigners in the UK and US (Weeks, 2015).

Yet, despite the GLF leaving its mark on LGBT politics and culture in the 1970s – the birth of the Pride March in Chicago in 1970, and London in 1972, can be linked directly to GLF activism – the rather loose organisational structure of the movement meant that it suffered from some of the same problems that afflicted the Women’s Liberation Movement, both in the UK and the US. By spreading itself widely, taking in international campaigns, and concealing the multitude of experiences and identities within the LGBT umbrella under one political and revolutionary platform, the movement began to fracture. In the UK, lesbian women felt marginalised by the GLF’s perceived focus on gay men, and due to their uncertain position within the WLM (Rees, 2010), began to explore separatist agendas (Weeks, 2015). In the US, members dismayed by the movement’s anti-capitalist agenda set up a separate organisation, the Gay Activists Alliance (Ashley, 2015). The GLF as a result of changing priorities and increasing demands for diversity in its campaigns did not so much disappear altogether, but spawned new movements with new focuses, and new objectives to confront new challenges, such as the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Despite these movements’ shortcomings and their disintegration in the 1980s, the GLF, just like the WLM, left its mark on the lives of its activists, and thousands of ordinary men and women, who were provided with a vocabulary through which to express their unwillingness to conform to hegemonic norms regarding gender and sexuality, and to envisage different ways of being a man or a woman.

References

Robinson, Lucy, Gay Men and the Left in Post-war Britain: How the Personal Got Political (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007)

Rees, Jeska, ‘A Look Back at Anger: the Women’s Liberation Movement in 1978’, Women’s History Review, Vol. 19, Issue 3 (2010), pp. 337-356

Ashley, Colin P. ‘Gay Liberation: How a Once Radical Movement Got Married and Settled Down’, New Labor Forum, Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2015), pp. 28-32

Meek, Jeffrey, Queer Voices in Post-War Scotland: Male Homosexuality, Religion and Society (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Weeks, Jeffrey, ‘Gay Liberation and its Legacies’ in David Paternotte & Manon Tremblay (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to Lesbian and Gay Activism (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), pp. 45-75

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free