Social Class and Gender Oppression

Share this step

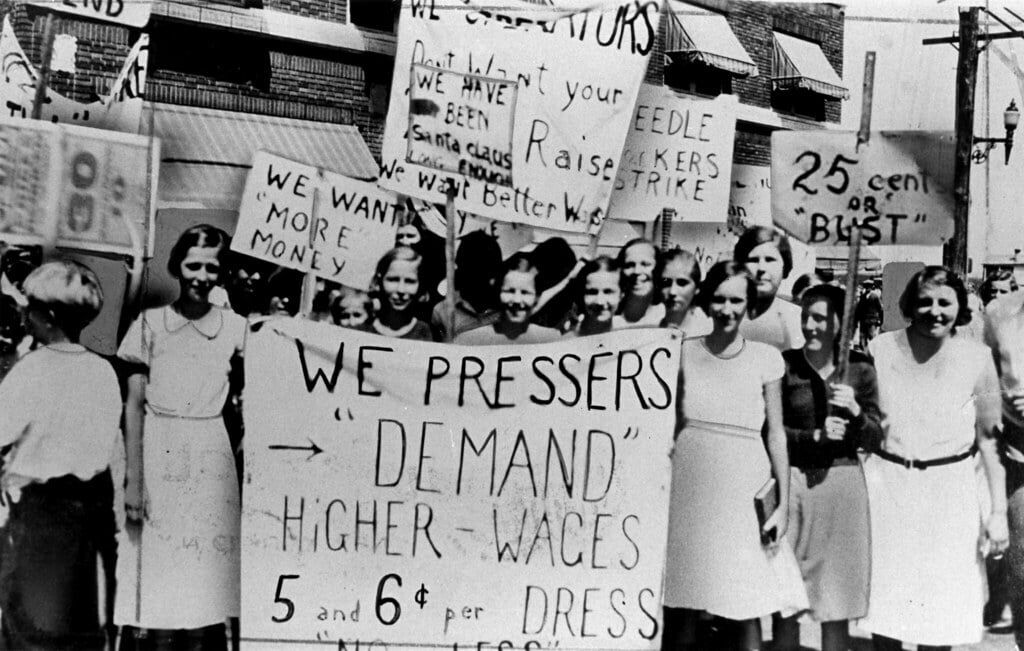

Different strands of feminist politics have focused on the intersections of class and gender oppression. While socialist feminism, going back to the early 19th century, has linked the liberation of the working class with women’s equality, in recent years the intersectionality framework is used to understand the relationship between these two realms of oppression.

The notion of class was coined by socialist and Marxist thinkers in late 18th Century Europe. It is a lens through which to understand the inequalities between rich and poor, the reproduction of those inequalities, the mechanisms of capitalist accumulation, and the exploitation of labourers in the workplace. Class consciousness has served as a call to action, and in the late 19th Century onwards, workers’ movements in Europe, Latin America and beyond adopted class as a key framework.

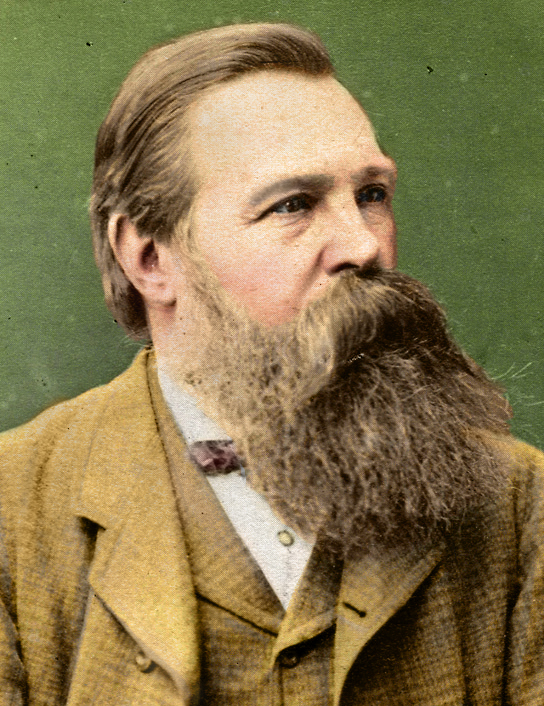

“Friedrich Engels portrait” by Artistosteles, CC BY-SA 4.0

“Friedrich Engels portrait” by Artistosteles, CC BY-SA 4.0

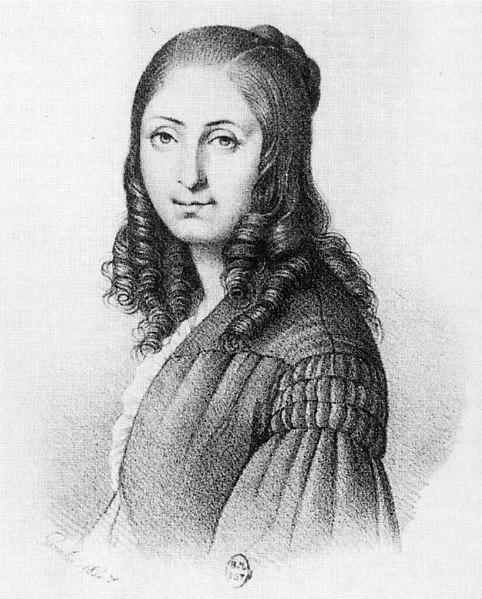

“Black and white portrait of Alexandra Kollontai “ by Rowanwindwhistler, CC PDM 1.0

“Black and white portrait of Alexandra Kollontai “ by Rowanwindwhistler, CC PDM 1.0

Thinkers such as Friedrich Engels (1820-1895) pointed at the family as the cornerstone of the capitalist order: as the transmission belt of social inequality through inheritance, and as the site of woman’s oppression through her role in reproducing the working class. Such analyses suggested that gender played a key role in the separation of private from public spheres, and of ‘productive’ from ‘unproductive’ labour – separations that are foundational to the capitalist order. However, by and large the socialist movements and regimes of the 20th Century did not achieve a significantly better record on women’s rights and equality than capitalist nations – despite the important critiques in this regard by leading women in socialist regimes, such as Alexandra Kollontai (1872-1952) in the USSR.

Generally speaking, socialist feminists understand oppression on the basis of gender and class to be fundamentally interlinked. They tend to focus on the family – its form, the legal and social relationships within it, and its economy – as the kernel of capitalist accumulation and exploitation. This is evident for instance in the ‘wages for housework’ campaigns of the 1970s-80s, which you looked at in week 3 of this course. In what follows, I explore the work of 19th Century French-Peruvian socialist feminist Flora Tristan (1803-1844), and highlight a more recent strand of socialist-feminist analysis and activism, the exploitation of women workers in multinational companies.

Flora Tristan, public domain

Flora Tristan, public domain

Tristan is often considered the first woman to have linked women’s and class oppression. Born in 1803 in Bordeaux, she was the illegitimate daughter of a Peruvian aristocrat, who left her and her mother nothing upon his early death. Growing up in poverty while being highly educated, Tristan never fitted into established social categories, leading her to claim the image of outsider or ‘pariah’. On her travels to Peru and England she noted the patterns of exploitation: for instance, it was in the sugar plantations in Lima, where she interviewed both slaves and slaveowners that she came to understand exploitation and the removal of liberty as not merely characteristic of but foundational to capitalism.

She was influenced by and close to anarchist and pre-Marxist socialist thinkers in France of the time, such as Charles Fourier and Claude Henri de Saint-Simon, whose notions of socialism were underpinned by moral, romantic and sometimes religious motivations. Similarly, Tristan’s understanding of justice for the working classes was often couched in a language of morality and charity, as in the vivid description of the misery of working-class families in the London slums in her 1840 book ‘My walks around London’. However, in The Workers’ Union (1843), she expounded a radical political vision of workers’ liberation. Five years before the publication of the Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels, and possibly influencing the authors, Tristan called for the creation of trade unions across industries, as a platform from which working men and women would do a number of things: organise in the workplaces for better pay and conditions, create educational institutions for the young and care infrastructure for the sick and elderly, and eventually take control of land and industry.

She argued that women’s rights and leadership were central to this programme. Her feminist radicalism stemmed from her rejection of the legal and social constraints placed on women in early 19th Century France. The July Monarchy and the legal framework of the Code Napoleon took away most liberties and right women had gained during the French Revolution, and women fared worse even in comparison with the pre-revolutionary era. Women did not inherit, were legally bound to ‘obedience’ to their husbands, and lost their property in marriage – an institution which Tristan qualified as hell.

In the 1830s she created an association for women attempting to be financially independent, and contributed to the leading feminist journals of the time such as La Tribune des Femmes. Yet these revolutionary views were underpinned by what one might consider traditional ideals of womanhood, inscribed in the romantic gender discourses of the time: she saw women as innately different from men, more altruistic and morally superior. Her call for women to lead, rather than follow the socialist revolution, was in fact informed by the belief that women were better suited to implement fairness.

Vertex, a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, the site of campaigns for better working conditions in the 2010s

Vertex, a garment factory in Dhaka, Bangladesh, the site of campaigns for better working conditions in the 2010s

One area which over the past 20 years has seen significant feminist theoretical production and grassroots activism centres on women garment workers in multinational companies in the developing world. Their exploitation uniquely sheds light on the intersections between gender, geography, and social class. It reveals the extent to which globalised capitalism relies on the creation of a class of easily dismissible and underpaid workers. Employing concepts such as the international gendered division of labour, feminist research builds on traditional socialist feminism by understanding women’s oppression as central to capitalist accumulation. It uses critical theories of globalisation to analyse the social impacts of the transfer of industrial production from the developed to developing world in recent decades. Such an anti-capitalist analysis crucially requires a feminist approach. It is only by analysing sex segregation on the labour market (which, indeed is a universal phenomenon and one of the most enduring characteristics of industrial labour markets), and it is only by understanding how this in turn relies on the sexual division of labour in the family and the community, that one can map the reasons why it are primarily women who are employed in these underpaid, precarious, and often dangerous jobs.

These socialist-feminist analyses were provoked by a wave of protests by women employed directly or indirectly by multinationals in the developing world since the 1980s. A case in point is Bangladesh, a country whose economy has since this period been increasingly dependent on the multinational garment industry. Today, this industry accounts for 80% of the country’s export revenue. Over 80% of those employed in the factories and workshops producing clothes and shoes for the US and European markets are women. They are underpaid, work long days and often in unsafe conditions.

Grassroots protests and strikes have erupted on a regular basis in Bangladesh since the 1980s, sometimes drawing on more traditional forms of community organising. The National Garment Workers’ Federation was established in 1984, and has since then fought for basic rights according to international standards on health, pay and social security. Today, it has over 27 000 members and more than half of its executive committee are women. They, alongside other unions, have in recent years obtained better health and safety legislation, maternity regulations, and wage increases – although there is a long way to go yet.

In conclusion, these forms of exploitation are structural – they form a core element of global capitalism, of neo-colonial North-South relations, and of a patriarchal organisation of the economy, now on a global scale, whereby women are pushed to the bottom of the ladder.

References

Máire Cross, The feminism of Flora Tristan (Berg, Oxford, 1992)

Sandra Dijkstra, Floran Tristan: Feminism in the age of George Sand (Verso, 2019)

Karen V. Hansen and Ilene J. Philipson, eds., Women, Class, and the Feminist Imagination: A Socialist-Feminist Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990)

Kollontai, Alexandra, Women Workers Struggle For Their Rights (1919) https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1919/women-workers/index.htm

Lapovsky Kennedy, Elizabeth (2008) “Socialist Feminism: What Difference Did It Make to the History of Women’s Studies?”, Feminist Studies. 34 (3)

Linda Y. C. Lim, ‘Capitalism, imperialism and patriarchy: The dilemma of third-world women workers in multinational factories’, in Carole R McCann, Sung-Gyong Kim, eds. Feminist Theory Reader: Local and Global Perspectives (Routledge 2003), pp 222-31.

Lydia Sargent, ed., Women & Revolution: A Discussion of the Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1981).

Flora Tristan, The Workers Union. Translated by Beverly Livingston. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1983, 77-78.

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free