Gendering the past

By Dr Tanya Cheadle

The histories we choose to research are invaluable to us in the present: they root us in our culture, provide new perspectives on our societies, and inform our understanding of the human condition. It is therefore vital that we find ourselves and our experiences represented in these accounts. While traditional histories tend to focus on wars, rulers or international politics, a gendered and sexual approach centres the voices of those previously at the margins of history. It recasts the lives of women, lesbians, gay men and trans people as legitimate subjects for study and reinserts their stories back into historical narratives. This objective – of writing marginalized voices back into history – reflects the origins of women’s, queer and trans history in the social justice movements of the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, and is evidenced in the titles of early books of feminist history, such as Sheila Rowbotham’s Hidden from History (1973) and Barbara Mayer Wertheimer’s We Were There (1977).

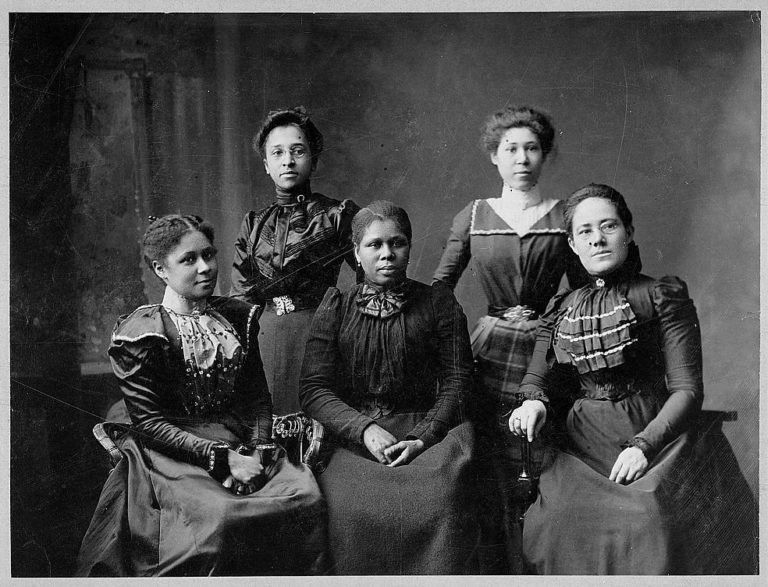

“Officers of the Women’s League, Newport, Rhode Island (1899”) African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition / Public domain

“Officers of the Women’s League, Newport, Rhode Island (1899”) African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition / Public domain

While such reclamation work remains a vital strand within gender history, the discipline does much more than this. By applying the categories of gender and sexuality to the past, our understanding of almost any aspect of history can be transformed, even when women or LGBTQ+ people have been absent. For example, historians of Empire now acknowledge the critical role played by gender in legitimizing imperialism, as European male colonizers depicted themselves as manly, rational and civilized in contrast to the ‘other’ of the effeminate, sexually deviant and barbarous people they colonized. Similarly, accounts of industrialization are now being rethought, incorporating feminist definitions of ‘work’ as a gendered category and factoring reproductive and caring roles into economic modelling. Finally, it has become impossible to consider the European Enlightenment as the harbinger of reason, liberty and progress in any straightforward sense, when you consider its ambiguous impact on women and gender equality.

‘From the Cape to Cairo’, Puck (10 December 1902) https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.25696/

‘From the Cape to Cairo’, Puck (10 December 1902) https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca.25696/

Gender history then, can best be understood not as the study of a particular group of historical subjects, but rather as an approach, one which sharpens and enriches our analyses of the past. So what do historians of gender actually study?

First, gender historians track changing codes of femininity and masculinity. We recognize that so-called ‘natural’ gendered attributes – for example that women are intuitive, selfless or emotional, or that men are rational, assertive and risk-taking – are in fact constructed by culture. They are specific to a particular historical and geographical moment and change over time. As Simone de Beauvoir famously said in The Second Sex, ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’ (1973) and this process of ‘becoming’ is conditioned by the attitudes in circulation in a society at any given time. One way that historians underscore this distinction is by using the term ‘sex’ to refer to the biologically-sexed body and ‘gender’ to refer to culturally-attributable qualities. An obvious historical example of a gendered code is the nineteenth-century Western discourse known in Britain and America as ‘separate spheres’ or ‘the cult of true womanhood’, which dictated that women’s ‘natural’ maternity and piety ideally suited them to caring duties in the home, justifying their lower wages relative to male ‘breadwinners’ and their exclusion from the professions. Or the persistent association between masculinity and militarism, which has propelled generations of professional and conscripted male soldiers to war, based on their ‘inherent’ bravery, stoicism and aggression, and the paternal need to protect women and children.

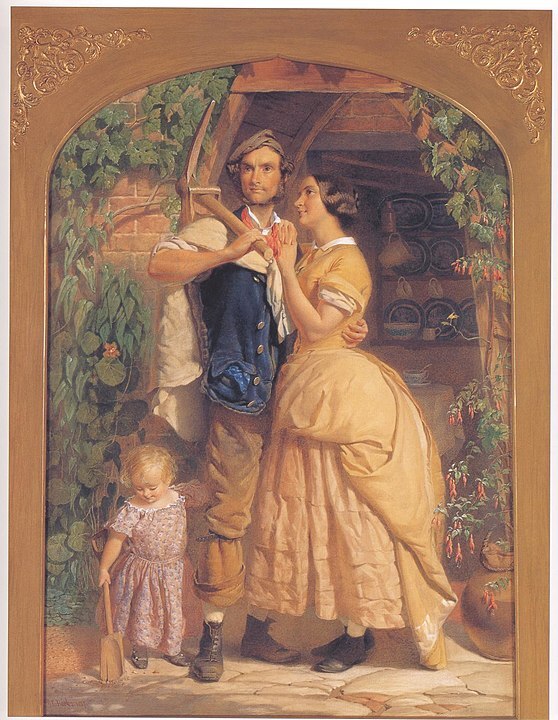

George Elgar Hicks, ‘The Sinews of Old England’ (1857) By George Elgar Hicks – “Gender in Victorian paintings”, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18455949

George Elgar Hicks, ‘The Sinews of Old England’ (1857) By George Elgar Hicks – “Gender in Victorian paintings”, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18455949

A second preoccupation of gender historians is the operation of power. A study might entail an examination of patriarchy within a historical context, although scholars have moved beyond simplistic models of male domination and female exploitation, and instead recognize the numerous ways in which patriarchy has been negotiated, contested and legitimated by both women and men on an everyday basis. Gendered power is also now understood to be intersected by other social identifiers, such as race, class, sexuality, disability, and age. A focus on power relations might therefore include how it has been wielded by a nineteenth-century woman philanthropist over the female prostitutes she is ‘saving’ from ruin, or by a white, European memsahib over her Indian, male servants.

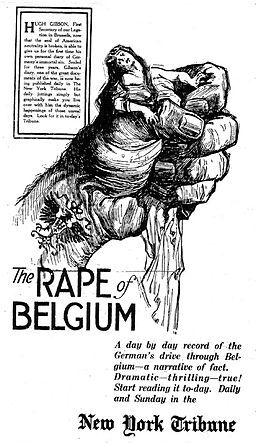

Finally, gender historians pay attention to the symbolic use of gender to signify relations of power. This is based upon the insight that implicit within the binary of woman/man is an assumption of a hierarchy, with gendered language and imagery most often used to naturalize and legitimate acts of domination or conquest. One historical example is the visual propaganda deployed during World War One, in which Belgium was represented as a female victim of Prussian sexual brutality, drawing on normative understandings of male hypersexuality and female vulnerability to silence opposition to the war.

The Rape of Belgium’, New York Times c. 1917: unknown (work for hire for New York Tribune) / Public domain

The Rape of Belgium’, New York Times c. 1917: unknown (work for hire for New York Tribune) / Public domain

To conclude then, gender history is best understood as an analytical approach. It might entail an examination of the shifting cultural codes of masculinity and femininity in any given period, the intersectional operation of power within a family, organisation or nation, or a study of the symbolic use of gendered language and imagery to justify hostile acts. However it is employed, the ultimate aim of gender history is to help us write more inclusive, perceptive and relevant historical accounts.

Further Reading

Laura Lee Downs, Writing Gender History (London: Bloomsbury, 2010)

Sonja O. Rose, What is Gender History? (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012)

Joan Scott, ‘Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis’, American Historical Review 91 (1986), pp. 1053-75

Share this

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

A Global History of Sex and Gender: Bodies and Power in the Modern World

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free