Lombroso and the ‘criminal type’

Share this step

Having looked into all of those faces of people who had been convicted or were suspected of being offenders, we are now going to reflect on ideas about the appearance of law breakers. In the nineteenth century, people commonly linked certain physical traits with criminality and their assumptions were backed up by pseudo scientific theories.

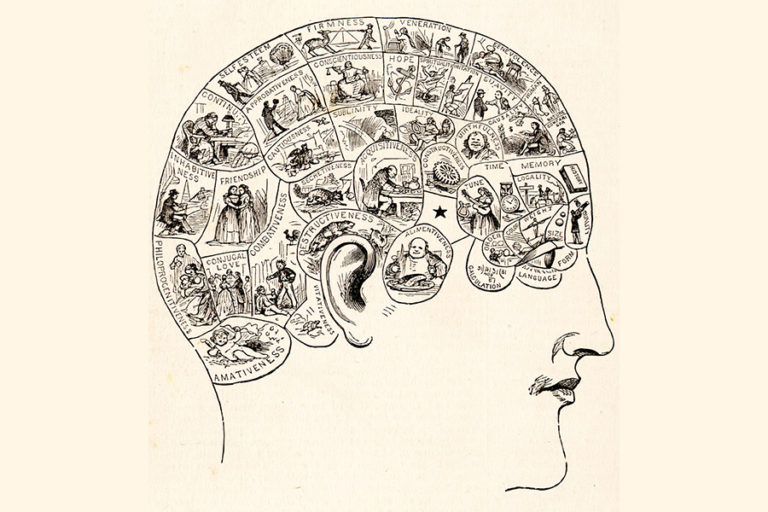

The first of these theories was phrenology. Phrenologists believed that the brain was made up of different ‘organs’ or zones, each one relating to a specific aspect of the personality and character. Well developed propensities, sentiments and faculties created a bump on the skull while flat areas or dips showed that the related area was less developed in that person. Someone who was destructive, for example, would have developed a bump over their right ear, where this character trait was believed to reside. Skulls then were seen as literally hard evidence of a person’s character and characteristic behaviours, and a predictor of their future behaviour. The founder of phrenology was Austrian physician Franz Gall who published on the topic between 1800 and 1830. His ideas were popularised in Britain by his colleague Johann Spurzheim and were carried to Australia, where, as in other colonial settings, there was particular interest in the skulls of Indigenous people.

A phrenology diagram (1883) © Wikimedia Commons

A phrenology diagram (1883) © Wikimedia Commons

Research linking physical traits with behaviour was facilitated in Britain by the Murder Act of 1752 which decreed that the bodies of executed criminals could not be buried in consecrated ground but, to deepen their punishment, should be hung in chains in a gibbet to slowly and publicly decompose or could be dissected for medical purposes (Tarlow, 2016). The vast majority of bodies of criminals were turned over to medical schools where they were much needed for the training of doctors. This allowed for very close studies of criminals’ skulls and skeletons and triggered interest in whether they were typical of the whole population, or might have traits that differed from non criminals.

One of those who became very interested in the physical commonalities between criminals was an Italian army doctor named Cesare Lombroso. Now credited with being the founder of criminology as a field of study, Lombroso published his book Criminal Manin 1876, and then in another four editions; followed by Criminal Woman in 1893.

Lombroso argued that criminals could be identified through general characteristics they shared with one another, which he designated as composing a criminal type. His core idea was atavism, which means that he understood criminals to be evolutionary throwbacks who were inferior to non criminals. While he was the first person to study criminals using scientific methods, his work was clearly informed by long term prejudices European people had about the origins of crime and who was most likely to behave in criminal ways.

Lombroso built on these prejudices, developing tools to measure body parts with great precision and tests designed to determine sensitivity to pain and propensity to lie, including a very basic lie detector. Lombroso collected items related to criminals as he conducted his research, extending to death masks and skulls.

He opened a museum of these objects in Turin, Italy in 1896 which remained open to the public until 1948, and reopened in 2001. Next time you are in Turin, go along to the Museum of Criminal Anthropology and you can see Lombroso’s own skeleton there, donated when he died in 1909, and the head of the first criminal he examined, thief and arsonist Giuseppe Villella – retained after a court action by his family to have it returned to them failed in 2012.

Drawing on his examinations of actual criminals and Darwin’s recently published theory of evolution (1859), Lombroso concluded that criminals had features more like those of the apes from which humans had descended and the Indigenous peoples (in his terms ‘savages’) who were thought to be closer to those apes. Have a look at the photographs you selected as I go through Lombroso’s description of the criminal type. In his view, law breakers would be expected to have larger, protruding jaws, higher cheekbones, larger less symmetrical faces with more crests, grooves and depressions, more prominent ridges above the eyes, and ears more closely attached to the head, of unequal size or unevenly placed on the head than the general population. Their eyes were hard, frequently with drooping eyelids and could be unequal in size or colour while their teeth tended to be large and well separated and their skin was heavily wrinkled. The born criminal’s hair was more typical of opposite sex, abundant in women and scanty in men, while eyebrows were bushy and could be slanted or meet across the nose. Arms were excessively long, like those of apes and hands might have extra or missing fingers with pronounced webbing. Other typically criminal traits according to Lombroso were a high pain threshold which led, amongst other things, to enjoyment of being tattooed; acute sight; idleness; strong sexual urges and a craving for evil. Lombroso concluded:

These anomalies in the limbs, trunk, skull and, above all, in the face, when numerous and marked, constitute what is known to criminal anthropologists as the criminal type, …they are [not] the cause of the anti-social tendencies of the criminal… They are the outward and visible signs of a mysterious and complicated process of degeneration, which in the case of the criminal evokes evil impulses that are largely of atavistic origin. – Gina Lombroso-Ferrero, Criminal Man According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso (New York, 1911)

Theories of criminality like phrenology and Lombroso’s criminal type have long since been discredited and discarded. Lombroso’s theories were deeply embedded in the racist assumptions of the late 1800s and early 1900s when around the world, people of European origin were finding ways to articulate and institutionalise race as a concept, to their own advantage. There is no longer any sense that, as Lombroso claimed, the criminal ‘reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals’.

However, returning to our theme of identifying underworlds, for law enforcement agents and the general public at this time, being told that criminals had a distinctive appearance was very helpful. It made it much easier to place the blame on those who happened to have these characteristics, whether or not they had actually broken the law.

References

Sarah Tarlow, ‘Curious afterlives: the enduring appeal of the criminal corpse’, Mortality, 2016. pp 210–228.

Share this

Casing the Joint: Introducing Histories of Crime

Casing the Joint: Introducing Histories of Crime

Reach your personal and professional goals

Unlock access to hundreds of expert online courses and degrees from top universities and educators to gain accredited qualifications and professional CV-building certificates.

Join over 18 million learners to launch, switch or build upon your career, all at your own pace, across a wide range of topic areas.

Register to receive updates

-

Create an account to receive our newsletter, course recommendations and promotions.

Register for free